Fighter pilot Captain Brian Bews was rehearsing for an air show in Lethbridge, Alta., on July 24, 2010, when one engine of his CF-18 Hornet died. He ejected only 90 metres from the ground; two seconds later, his jet was a fireball and he was floating to earth.

Bews had just become eligible for the Caterpillar Club, an exclusive group no one really wants to join: those who survived by parachuting from an aircraft that crashed.

No one knows exactly how many people have been saved by parachutes, though just one manufacturer—the Irvin Air Chute Company (later Irvin Aerospace, now Airborne Systems)—has rescued more than 100,000.

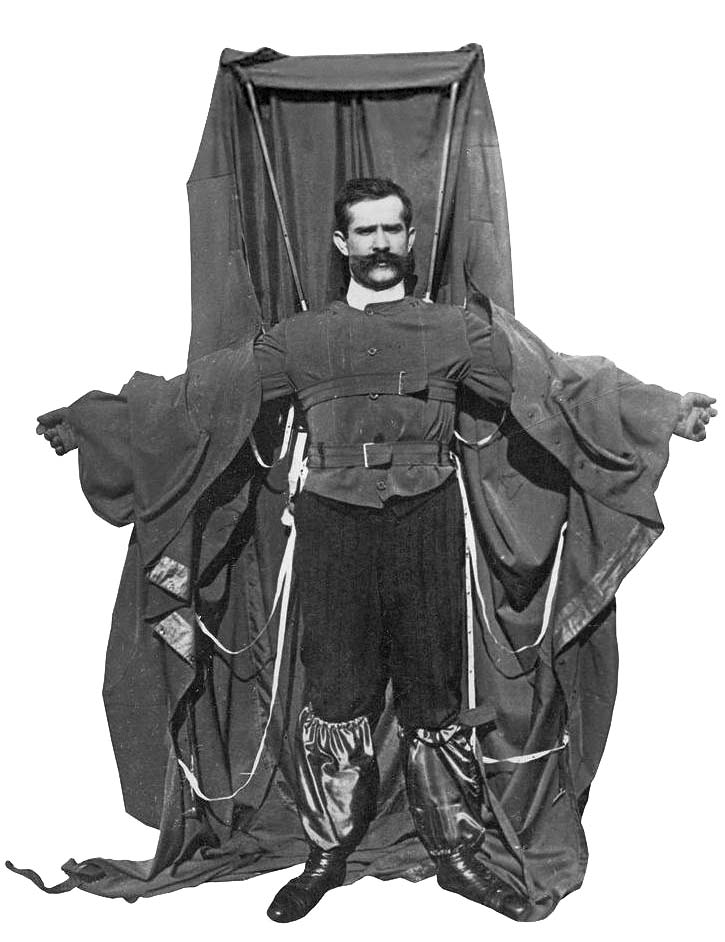

First World War parachutes were scarce and were inconveniently stored aboard observation balloons and aircraft. Tailor Franz Reichelt invented the wearable parachute, but was killed in a demonstration jump from the Eiffel Tower in 1912, captured on macabre newsreel footage. In 1919, Leslie Irvin, nicknamed Sky-Hi, tested a wearable parachute with a ripcord, designed by the U.S. Army Parachute Section, and went on to manufacture them.

Captain Brian Bews ejected moments before his CF-18 Hornet became a fireball. [The Canadian Press/9894388]

Irvin formed the Caterpillar Club in 1922 to recognize crash survivors who had used Irvin parachutes. Named for the silkworms that provided material for early parachutes, the club issued membership cards and gold caterpillar pins with ruby eyes. They were changed to gilt and garnet during the Second World War, then 10-carat gold-filled with enamel eyes. “The number of applications we now receive, I am very pleased to say, is very small—two or three a year,” said Maureen Udy of Airborne Systems Limited in England.

Parachuting pioneer Franz Reichelt before his doomed leap from the Eiffel Tower in 1912. [Wikimedia]

Soon other companies also issued mementoes: plaques from Pioneer Parachute Company; kangaroo pins from Australia’s Roo Club; and gold and silver pins from the Switlik Parachute Co., which had outfitted Admiral Richard Byrd and Amelia Earhart. Earhart made the first public jump from the company’s 50-metre parachute training tower. She described the descent as “loads of fun!”—an opinion shared by sport jumpers to this day.

Leslie Irvin (right), inventor of the Irvin Air Chute, looks on as U.S. Army Air Corps Master Sergeant Ralph Bottriell (centre) prepares for a test jump, accompanied by pilot James Ray. [Wikimedia]

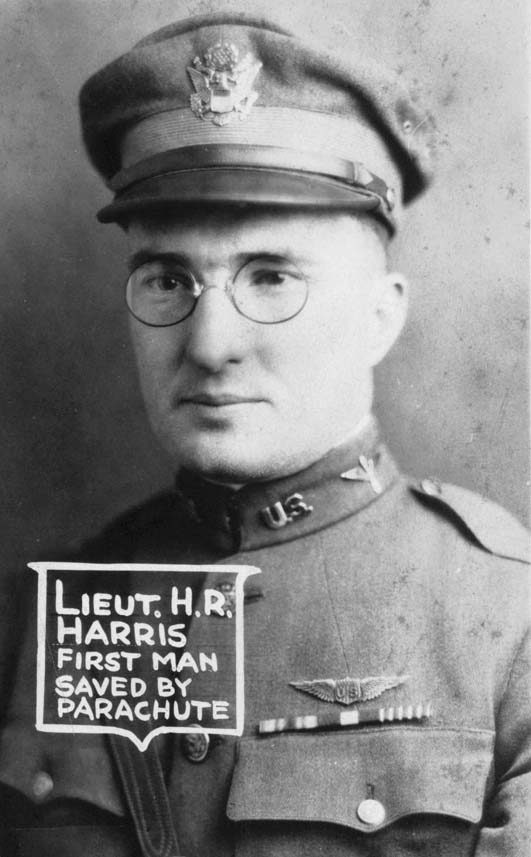

On Oct. 20, 1922, Ohio test pilot Lieutenant Harold Harris (above) became the first Irvin Caterpillar Club member. The first Canadian member was Jack Caldwell, who—due to engine failure—bailed out of the Vedette he was testing over the Canadian Vickers factory on May 17, 1929, according to Harold Skaarup, author of Canadian Warplanes. Fabled flyer Charles Lindbergh and astronaut John Glenn were also members.

More than 13,000 Royal Air Force and RCAF aircrew, many PoWs, applied for membership during the Second World War. Only a fraction of those eligible have applied to join the club, says a club brochure, including Luftwaffe crew, most of whom carried an Irvin-designed parachute from a factory bought by the Nazis in 1936.

No one who can substantiate their claim is denied membership. Key to the claim is the fate of the aircraft. Deliberate jumps don’t qualify, so a skydiver whose plane later crashes would not qualify, but the plane’s pilot would.

In historic irony, Sky-Hi Irvin made more than 300 parachute jumps—but never was eligible to join the club he founded.

April 9, 1958

Date of highest parachute escape, according to Guinness Book of World Records, during a failed test flight of a Royal Air Force English Electric Canberra jet bomber

3,048 metres

Height at which parachutes of Canberra jet pilot John de Salis and navigator Patrick Lowe deployed

17,070 metres

Altitude at which their Canberra jet exploded

8,848 metres

Height of Mount Everest

July 26, 1959

Date Lt.-Col. William Rankin of the U.S. Marine Corps bailed from his F-8 Crusader jet fighter

14,326 metres

Height at which the engine on Rankin’s jet fighter failed

40 minutes

Time it took Rankin to descend, due to a thunderstorm’s vertical air currents forcing him upward

11 minutes

Expected descent time

Canadians can still join the Irvin Caterpillar Club. Application forms are available from Yvonne.wade@airborne-sys.com.

Top Photo: A Membership card for the Caterpillar Club. / National Air and Space Museum Archives: 80-2393

Advertisement