Flight Lieutenant Miller Gore depicts a Second World War Allied bombing raid over Germany [Flight Lieutenant Miller Gore/CWM/19710261-1436]

By 1944, the Allied aerial offensive against Nazi Germany was reaching its crescendo, in both damage inflicted and casualties taken. Flying from Britain, squadrons of the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command were engaged in nightly battles with the Third Reich, itself armed with formidable anti-aircraft and fighter defences. Many of the bomber crews were Canadians serving with the RAF or in No. 6 Group, Royal Canadian Air Force, an all-Canadian division co-ordinating its efforts with the overall campaign.

It was gradually becoming apparent to the airmen and their commanders that this form of warfare—conducted by the newest and most glamorous branch of the military, using the most advanced technology in the world—had an attrition rate comparable to the bloody trench slaughters of the First World War. How to convey this realization to citizens back home? And to convince them that the mounting sacrifices of their husbands, brothers and sons were worth it?

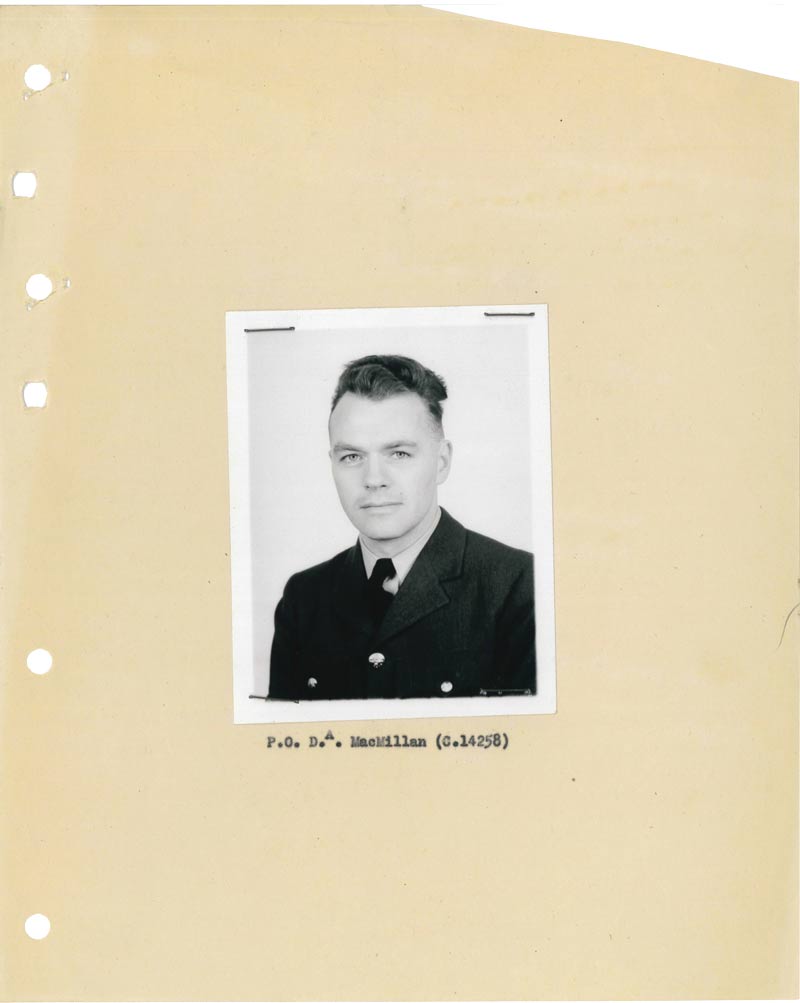

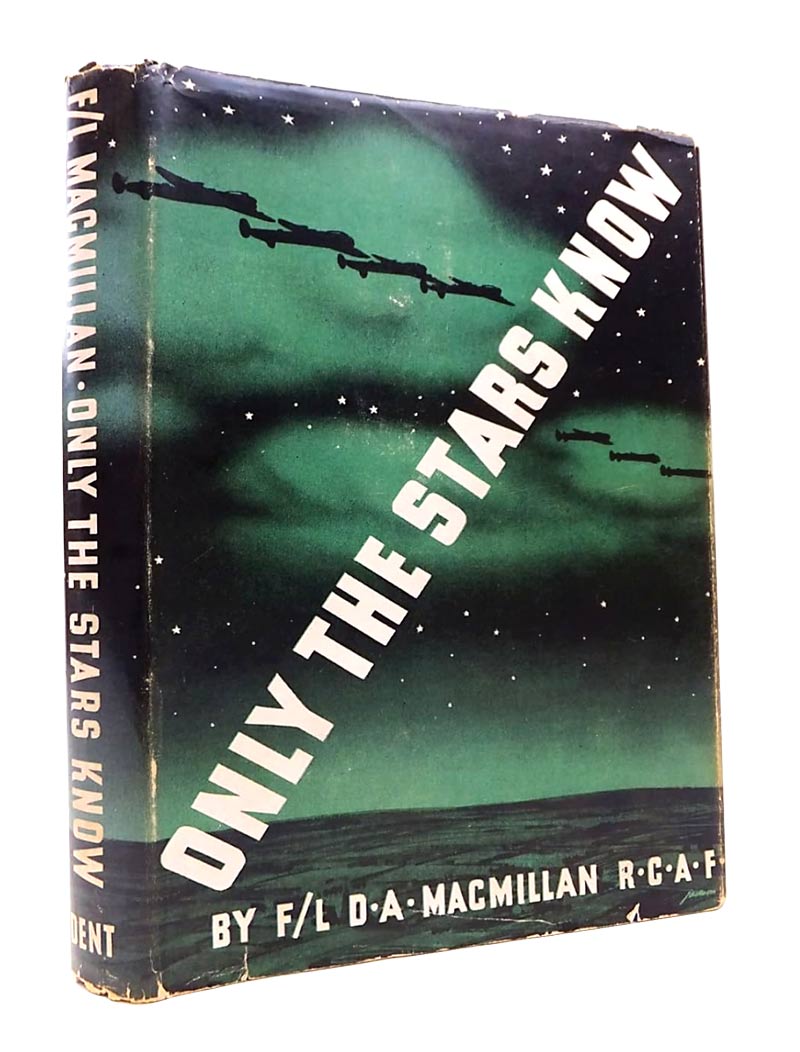

Flight Lieutenant Donald A. MacMillan’s Only the Stars Know, a series of fictionalized—though hyper-realistic—accounts of bomber crewmen, was published in 1944. Readers were eager for similar non-fiction accounts [Courtesy of George Case]

[Stella & Rose’s Books]

In the autumn of 1944, a 138-page book titled Only the Stars Know was issued by the Canadian arm of J.M. Dent and Sons, a large British publishing house. Written by Flight Lieutenant Donald Archibald MacMillan of the RCAF, the work offered a series of fictionalized vignettes about life—and death—among the men of No. 6 Group.

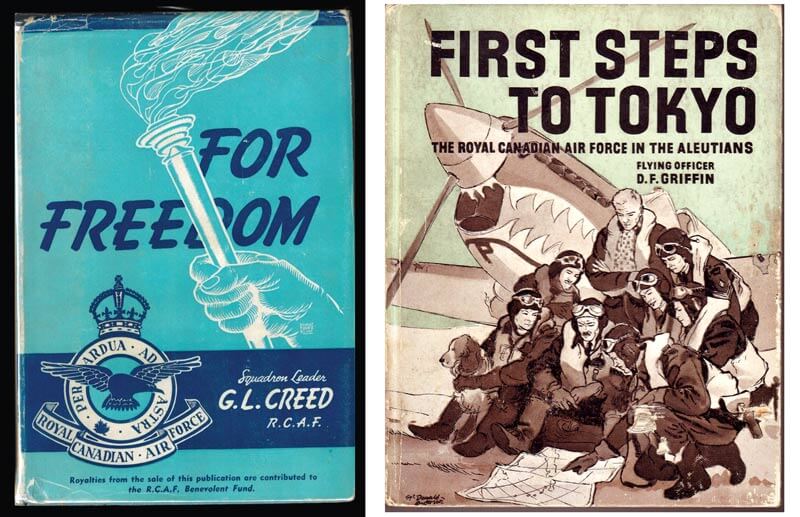

The market for nonfiction books and novels about the ongoing war, especially first-hand accounts written by uniformed fighting personnel, was already large: Dent alone had previously released For Freedom, a collection of poetry by RCAF Squadron Leader G.L. Creed, and the pictorial volume First Steps to Tokyo: The Royal Canadian Air Force in the Aleutians, by Flying Officer David F. Griffin.

[AbeBooks; Amazon.com]

Only the Stars Know fell into the same broad category of morale-boosting, patriotic material pitched to what was generally known as “the war effort”—and as with For Freedom, dust jacket and inside copy promised that royalties would go to the RCAF Benevolent Fund—yet MacMillan’s subtler themes made his book resonate more with the audience most affected by his subjects of duty, bravery and loss, both upon its publication and ever since.

Although one of its chapters was later included in the 2001 anthology Great Canadian War Stories, Only the Stars Know is not a literary landmark. If MacMillan has an identifiable style, it might be classed with the mid-century Canadiana of Hugh Garner, another writer whose fiction featured ordinary small-town characters touched by the Great Depression and WW II, or roughly a northern equivalent to John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men. Steinbeck, coincidentally, contributed the journalistic Bombs Away! The Story of a Bomber Team, to the U.S. mobilization in 1942.

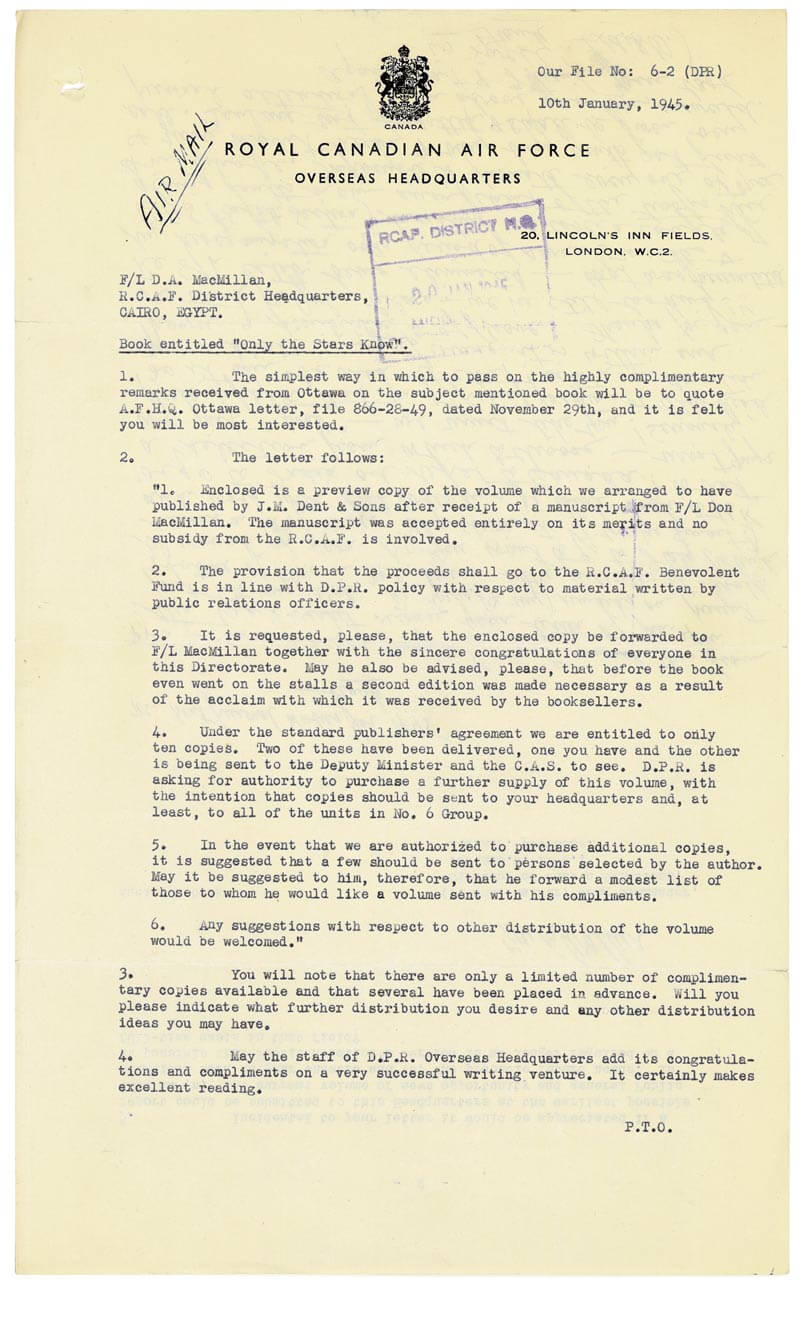

A Royal Canadian Air Force letter to MacMillan about Only the Stars Know notes that sale proceeds were to go to the RCAF Benevolent Fund.[LAC]

The book won favour from reviewers who welcomed its insights into a conflict not yet safely resolved.

MacMillan, Garner and their generation of writers were eventually made passé by the likes of more postwar sophisticated authors such as Robertson Davies, Mordecai Richler, Margaret Laurence and other Canadian novelists. But in 1944, Only the Stars Know won favour from reviewers who welcomed its insights into a conflict not yet safely resolved.

The Winnipeg Free Press noted that, “Few books of real literary merit have come out of the present war—fewer will outlast it, but in Only the Stars Know is the wonderful, moving story which we believe will be read many years after the new world has come into being. [The book] is a story of the young and strong who died far from home in a battle of rights which they did not fully understand.”

Chapter title pages from Only the Stars Know. [Only the Stars Know]

A reviewer in the Ottawa Citizen, meanwhile, wrote, “We have in this volume not so much the conventional account of routine operations demanded by the Press Associations as a pen portrait gallery of sensitively drawn sketches.” The Globe and Mail concluded: “The author knew personally all the boys of whom he writes and out of his knowledge and love of them he has written a book that, while at times moving the reader to tears, will almost burst his heart with pride and admiration.”

Donald Archibald MacMillan was born in Regina in 1911. After stints teaching at country schools, selling articles and fiction to national magazines, reporting for his hometown Daily Star and Leader-Post and at radio stations CKCK in Regina and CKOC in Hamilton, he joined the RCAF in September 1942.

Turned down for flight training due to substandard vision, his background as a writer and broadcaster made him valuable in recruiting drives out of Edmonton and Saskatoon. “I regard this officer as one of the most able public relations men in the service,” a superior noted in his personnel file.

MacMillan went overseas in 1943 and was stationed at the headquarters of No. 6 Group from August to May the next year, at the very climax of the Allied bombing campaign. He was later sent to the Middle East and worked out of Cairo and Tel Aviv until the end of the war.

MacMillan’s second and last book, Rink Rat. [AbeBooks]

He returned to civilian life in 1945 and wrote one other book, a small-town hockey story called Rink Rat, published by Dent in 1949. Like many other authors with bills to pay and a family to raise, MacMillan found steadier income as an advertising copywriter, first joining the Toronto agency of Young & Rubicam, then working for Cockfield Brown until retirement. He died in 1983, survived by a wife and two children. His obituary noted Rink Rat and Only the Stars Know as his published legacies.

While the latter was not officially an RCAF publication, MacMillan’s position in the air force, his access to No. 6 Group bases in Yorkshire and his rank implied the military’s tacit approval of the book. Though public relations today carry the impression of spin and deception, in 1943 the unprecedented scale of social and industrial organization required by the war meant that promoting the RCAF’s continued relevance to ordinary Canadians—far from the fighting and unfamiliar with the principles and methods of strategic bombing—was vital.

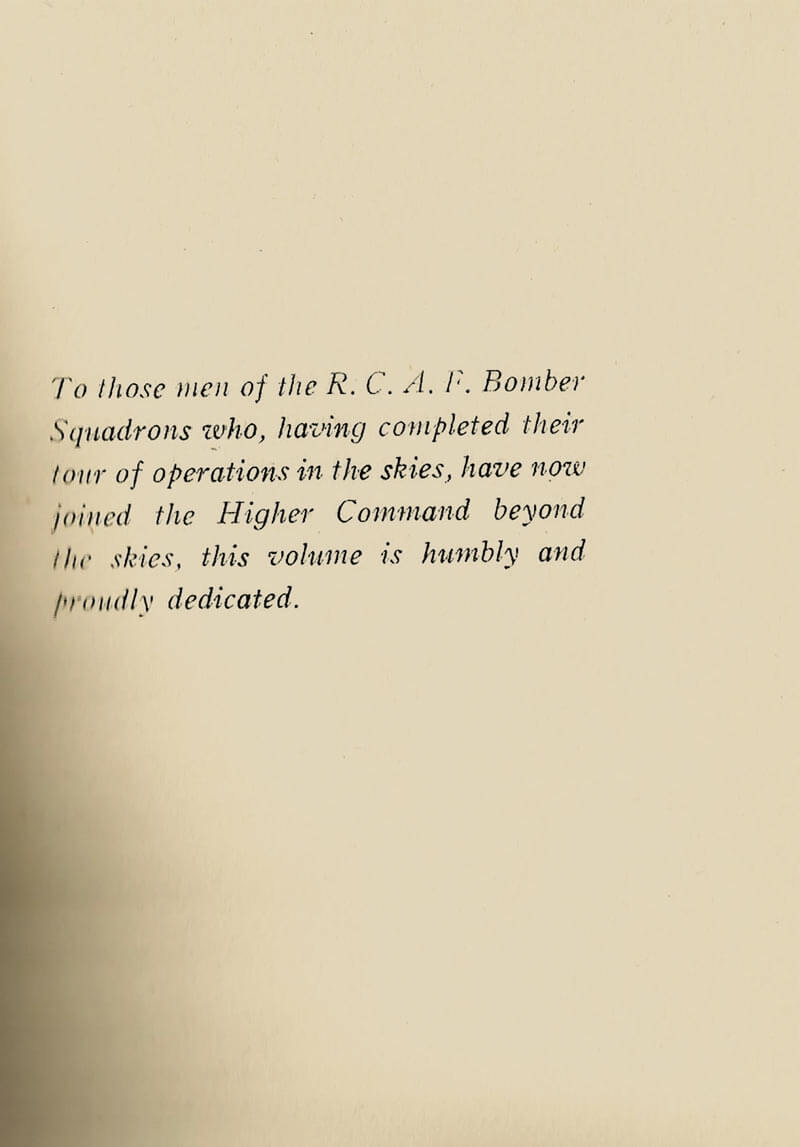

The dedication in Only the Stars Know.[Only the Stars Know]

Much of MacMillan’s job would have involved attending debriefings of returned bomber crews and transcribing their accounts into press releases for Canadian newspapers, with suitable quotes from individual airmen identified by their hometowns. All service branches employed teams of public relations officers at the time, working out of various theatres and units, feeding stories, photos and radio spots to an array of media outlets. The RCAF even had its own tabloid, Wings Abroad.

“He liked writing these stories,” wrote the reporter turned airman in one of the vignettes in Only the Stars Know titled “The Newspaper Writer.”

“It was little enough, but he could imagine some mother or father at home clipping them from the paper and saving them through the years.”

Some of the book’s entries may have been meant as understated propaganda for the Allied cause: the personifications of British, American and Commonwealth servicemen harmoniously integrated into Canadian crews; the loyal admiration of plucky English resilience; the unquestioned faith that strategic bombing was a worthwhile allocation of human and material resources in the fight against Hitler (something subsequent analysis would cast into serious doubt).

Still, other passages are remarkably gloomy. Most of MacMillan’s fictional fliers, for instance, don’t survive: Bill, the quiet wireless operator briefly drawn out of his shell by an extroverted pal; Johnny, the hardened tail gunner from a bad part of town; Jumbo, the naive farm boy promoted to wing commander for his simple courage.

The book even alludes to the real-life Nuremberg raid of March 1944 in which a staggering 90-plus Bomber Command planes were lost.

Across the brief profiles, the recurring message is that flying RCAF bombers is dangerous, and many airmen die in the line of duty. After the war, these truths were brought home in the films Appointment in London (1953) and The Dam Busters (1955), and in Len Deighton’s classic novel Bomber (1970) and Canadian Spencer Dunmore’s Bomb Run (1971). But Only the Stars Know made similarly honest observations of a battle that was still being waged.

MacMillan’s title alludes to both the RCAF motto Per Ardua ad Astra—Through Adversity to the Stars—and to the haunting uncertainty of the fates that befell so many of its members.

Men killed on bomber operations often died alone at night over enemy territory, with no record of their final minutes; sometimes an entire crew of six or seven was simply struck off strength after a mission, their deaths unseen by fellow fliers. Performed as a kind of shift work, there was a surreal disconnect between the relative safety and comfort enjoyed by off-duty aircrews and the extreme danger of their combat roles, something the book tried to convey.

“It dawned on you that this was a new way to fight a war: that it was utterly remote and different from that other war, where men fought in the trenches,” wrote MacMillan in the chapter “This Is Bomber Station.”

“It was a swing-music-on-Monday-night, maybe-dead-on-Tuesday existence….You lived, as it were, at a gentlemen’s club. Then you went out and died with your well-polished boots on.”

Nearly 10,000 Canadians were killed serving in Bomber Command. Copies of Only the Stars Know are still found in a few Canadian libraries or private collections. I have a copy, inherited from my father, who received it as a Christmas gift from his uncle Howard Case in 1944.

Howard’s son, Dad’s older cousin, was Thomas Edward (Ted) Case, from Kelvington, Sask., an RCAF pilot who served with the RAF in Bomber Command. On the night of Feb. 19, 1943, Ted flew his Lancaster out of 156 Squadron’s base in England to take part in a raid on Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Neither he nor his crew were seen again. A few months after his final sortie, he was officially presumed dead. Postwar research revealed his plane was probably shot down by a German night fighter and crashed into the North Sea, but only the stars know.

The author’s distant cousin Thomas Edward Case served in Bomber Command.[Courtesy George Case]

An all-Canadian bomber crew from 419 Squadron. [Courtesy George Case; DND/PL-7096]

Perhaps MacMillan’s poignant little book provided a measure of comfort to Ted’s family and friends, reminding them that they shared their grief with thousands of other people whose sons, brothers, husbands and cousins, in the author’s words, “having completed their tour of operations in the skies, have now joined the Higher Command beyond the skies.”

After the war, my father remembered how he travelled with Uncle Howard to visit a memorial at the family ancestral home in Dungannon, Ont. Dad said that when they read the inscription for Pilot Officer Thomas Edward Case, missing over Germany in 1943, aged 20 years, his uncle broke down and wept.

“It was a swing-music-on-Monday-night, maybe-dead-on-Tuesday existence…You lived, as it were, at a gentlemen’s club. Then you went out and died.”

Advertisement