Squadron Commander Raymond Collishaw in a Sopwith Camel, July 1918. [CWM/19930012-308]

As a first officer in the Canadian Fisheries Protection Service with years of sea experience, Collishaw of Nanaimo, B.C., expected to be welcomed into ranks of the Royal Canadian Navy during the First World War.

But that service didn’t snap him up, so he joined the Royal Naval Air Service instead. He went on to become a Great War Canadian air ace, then served in WW II, as well.

Canada didn’t have its own air force during WW I, so Collishaw was among some 35,000 Canadians who served as pilots, observers and aircrew with the British flying services. He began his training in Canada but went to Britain in January 1916 to complete his qualifications.

“His training was not without colour,” wrote retired lieutenant-colonel David Bashow in Intrepid Warriors: Perspectives on Canadian Military Leaders.

In the days before radio communication, pilots and observers were taught how to drop messages in weighted bags to forces on the ground. Collishaw was asked by a fellow pilot to fly over his girlfriend’s yard and drop a note. On this Cupid’s mission, his engine cut out a mere 15 metres above ground. He had a crappy landing, crashing into a row of outhouses, wrecking his aircraft and covering himself and his plane with olfactorily objectionable latrine contents.

“I have never had a worse experience. I had been eight and a half hours in the air, mostly over Germany, and I am sure I don’t want anything like it again.”

Collishaw got better quickly, and had to, given the quality of machines just seven years after Canada’s first powered flight. On July 11, he was flying much higher on a 90-kilometre flight in England when he fought engine failure again. He was skilled enough to land—albeit hard—in a farm field.

Collishaw was considered a better than average pilot when he graduated and was posted to No. 3 (Naval) Wing in France in August 1916. In October, he first encountered the enemy while flying fighter interference for bombers on a raid on Oberndorf, Germany.

Shortly thereafter, he scored his first confirmed victories during an attack by six German scouts while ferrying a new Sopwith 1½ Strutter biplane fighter to a base in France.

“I have never had a worse experience,” he wrote to a friend shortly after. “I had been eight and a half hours in the air, mostly over Germany, and I am sure I don’t want anything like it again.”

He later recalled in his autobiography Air Command: A fighter pilot’s story that “a stream of bullets…went right into my goggles, sending powdered glass into my eyes. I was hardly able to see at all and could do little more than fling my Strutter about, hoping it would hang together in one piece.”

He dived to escape enemy fire. “After some time I was able to see a little better although my eyes hurt dreadfully, and I realized that I was almost down to ground level.”

An enemy plane that had him in its sights smashed into a tree. Collishaw climbed and fired into the engine and cockpit of another German aircraft, which went down. He flew into cloud cover to escape from the others.

“Finally, after what seemed an eternity, there was no more gunfire and I realized that the remaining scouts had left, possibly because they were running low on fuel.”

Collishaw groped his way to the nearest aerodrome where, in the nick of time, he noticed something was off: there were German markings on all the planes. He turned his touchdown into a hasty ascent, pursued by two German aircraft.

“I jammed the throttle forward and managed to take off, although I clipped off the tops of two trees close to the field,” Collishaw said in the Cross & Cockade Journal.

He thought he was still in France, but winds had blown him into Germany. He had no map and no idea where he was. He headed west, flying over the French front lines during an attack near Verdun, over the trenches, and recognizing a French aerodrome, landed before he ran out of fuel.

After three days of nursing his wounded eyes, Collishaw returned to duty, which involved months escorting bombers to Germany and many dogfights with enemy aircraft. He was shot down in December but was unhurt. On Jan. 24, 1917, he was awarded the French Croix de Guerre with palm.

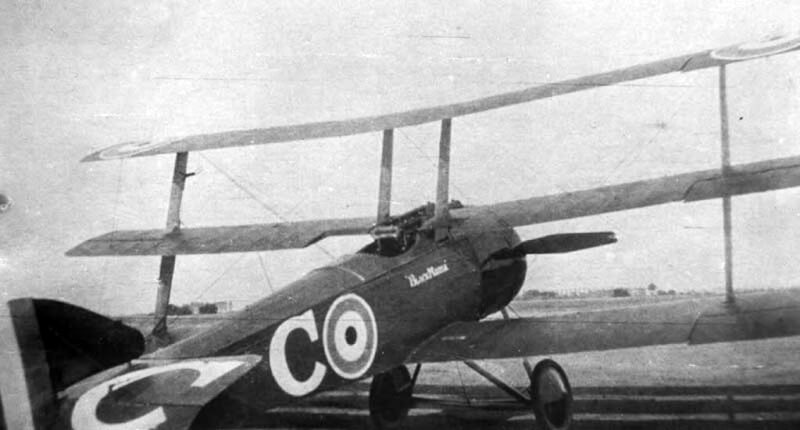

Collishaw’s Sopwith Triplane, “Black Maria.” [Wikimedia]

The craft responded nicely to controls, accelerated quickly, was stable during takeoff and when banked, had an adjustable stabilizer, and was equipped with altimeter and airspeed indicators. Pilot Peter Flett wrote home that the Sopwith Triplane “will be King of the Air before the summer is over.”

“The Sopwith Triplane was unique,” wrote Roger Gunn in Raymond Collishaw and the Black Flight. The three-winged craft was used exclusively by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), and fewer than 150 were manufactured. They were called Tripes or Tripehounds. Collishaw was piloting one on April 28 when he destroyed his fifth enemy aircraft, qualifying him as an ace.

The average life expectancy of a new British pilot in the spring of 1917 was 11 days. Attrition had whittled 3 Squadron down to 15 aircraft divided into three flights, designated red, black and blue with engine cowling and wheel covers painted those colours. The (initially) all-Canadian Black Flight named their planes Black Death, Black Sheep, Black Prince, etc. Collishaw, called Colly or Collie by comrades, piloted Black Maria.

In a two-month period, the squadron brought down 84 German aircraft, of which Collishaw contributed 33. That busy spring, pilots expected to fly at least several sorties a day, and dogfights were common.

“It was commonplace for contending antagonists to meet head on,” Collishaw later recalled. “At a distance apart of about 1,200 feet (365 metres), both opponents would open fire. Each could see his own and his opponent’s tracer bullets intermingling, and he could feel his aircraft shudder from the impact of bullets, while the near misses reacted harshly upon his ears.

“In about 3½ seconds of fire,” said Collishaw, “the intervening 1,200 foot interval was covered and the contending pilots tried to dodge collision. It almost invariably resulted in…a spinning waltz.”

“It was commonplace for contending antagonists to meet head on. At a distance apart of about 1,200 feet (365 metres), both opponents would open fire.”

Battle manoeuvres of the knights of the air often resembled dance moves.

“Pilots learned climbing turns called chandelles, and how to turn in the opposite direction of their opponent,” wrote Gunn. If both planes turned in the same direction, a pilot could find his opponent diving and attacking from above.

“If he turned first in the opposite direction and then rolled toward the enemy plane, he could pick up speed and find himself coming in under the enemy tail, ready to shoot.”

And as in a dance, each partner is acutely aware of the other.

“[S]harply banked, each pilot could watch one another’s face closely,” said Collishaw, as they vied to be the quickest to turn and get on the other’s tail.

Often in a dogfight a pilot would find himself attacking one enemy plane while another sneaked up to attack him from the rear. Three days after his first promotion to acting flight lieutenant in June 1917, it happened to Collishaw. A German fighter in his sights, Collishaw was the target of another enemy aircraft diving out of the sun. Bullets smashed into his cockpit, disabling his controls.

Collishaw recalled “thinking rather wistfully how nice it would be to have a parachute” during the 10 minutes or so the plane swooped and fluttered to the ground. The Triplane hit the ground at a favourable angle; it was destroyed but Collishaw suffered only bruises.

His British rescuers gave him “the type of stimulant that one might be expected to appreciate after such an experience.”

Collishaw and Captain A.T. Whealy in a Sopwith F. 1 Camel in Allonville, France, July 1918. [LAC/3214137]

“On the 24th June, 1917, he engaged four enemy scouts, driving one down in a spin and another with two of its planes shot away; the latter machine was seen to crash,” the citation also noted.

“The honours for being one of the highest scoring small units on the Western Front during the bloody summer of 1917 must surely go to the Black Flight of Naval 10,” wrote Bashow. In the Messines Offensive on the Ypres front, they faced “the cream of the German Air Force, including von Richthofen’s Flying Circus…and they soon locked in a form of ferocious, unrelenting combat.”

Black Flight brought down 68 enemy aircraft from July 1 to July 27; Collishaw was responsible for 30.

Collishaw was also a good leader. Black Flight ace William (Mel) Alexander gave one reason why: “This fellow Collishaw, I never saw him down, never once. No matter how bad things were—and they were pretty bad sometimes—he could keep built up. That was his long suit. Talk? He could talk his head off. Laugh? He was a wonderful fellow.”

The attitude was not accidental, Collishaw said in a CBC interview in 1969. “I deliberately adopted a policy of trying to make everybody happy. Some young fellas have a tendency to go to their cabins and mope—and think of the dangers of tomorrow whence they might be wounded or killed. So I [saw] to it that all the officers went to the mess and had a jolly good time there, sing-song and drinking…. And it worked, too.”

He too lived with the knowledge that everyday encounters could end in death. Lining up during a dogfight in mid-July, a German aircraft “appeared dead in front coming straight at me,” Collishaw recalled. He pushed the control column fully forward and passed just under the other aircraft in what is known as a negative-G (gravity) manoeuvre. It created such stress that his restraining straps snapped and he was ejected from the aircraft.

“This fellow Collishaw, I never saw him down. No matter how bad things were he could keep built up. He was a wonderful fellow.”

He managed to catch the top wooden struts. The aircraft “executed a series of extraordinary manoeuvres as it fell some 10,000 feet (3,048 metres); Collishaw felt “like a rag doll as my pilotless Triplane displayed its varied repertoire.”

Suddenly the Triplane pulled up sharply and Collishaw worked a leg into the cockpit, hooked his foot around the control column and managed to get the craft on level flight, after which he was able to get into the seat “a more sober and thoughtful pilot than I had been some moments before.”

On July 15 he was shot down. A piece of engine cowling was shot off and caught in the wing wires, throwing the aircraft into a spin. Collishaw frantically worked to regain enough control that when the plane crashed, only the aircraft’s undercarriage was destroyed and he was barely wounded.

Major Raymond Collishaw (centre) and the officers of No. 203 Squadron in Izel-lès-Hameau, France, on July 12, 1918. [LAC/3522198]

“Getting married during the war seemed tantamount to asking a girl if she would like to become a young widow,” said Collishaw. And immediately after the war, his foreign postings were too dangerous to allow for family accompaniment.

In November 1917 Collishaw returned to the war, a flight leader, then interim commander, of the Seaplane Defence Squadron, which provided protection for Royal Navy vessels, escorting RNAS bombers and conducting reconnaissance and offensive patrols.

In January 1918, he was promoted to squadron leader and given command of No. 3 (Naval) Squadron, which bombed and strafed enemy positions and troops during the German Spring Offensive. In March, the Germans had advanced to within nearly eight kilometres of Amiens, France. The squadron was assigned to the British First Army and moved closer to the front, some 60 kilometres to the northeast near Arras. Its Sopwith Camels were loaded with four 25-pound bombs and machine guns and made up to six sorties a day hunting targets.

In April, the Royal Air Force was formed in a merger of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Navy Air Service. Collishaw’s rank was changed to major and his squadron became No. 203 RAF Squadron. But he continued to wear the blue uniform of the RNAS.

“It was a sad moment when my squadron had to strike the Royal Navy ensign,” said Collishaw.

Originally forbidden to fly combat missions, he trained new pilots, giving them first shot, wrote Bashow, before “slipping into firing position himself and downing the enemy. He would then selflessly slap the newcomers on the back and congratulate them on their first aerial victory.”

But Collishaw soon returned to formal fighting—and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in August 1918. The citation lauds his leadership skills and “engaging the enemy with great bravery and fearlessness. Up to date he has accounted for forty-seven enemy machines, twenty-two in the last twelve months.”

A month earlier, Collishaw and pilot pal Leonard (Tich) Rochford attacked an enemy aerodrome. They bombed living quarters and hangars and strafed the Germans as they tried to move their planes out of a hangar. Collishaw attacked an aircraft descending over the aerodrome, bringing it down.

“His skills,” wrote historian Sydney F. Wise in Canadian Airmen in the First World War, had been “honed to a fine edge.”

Collishaw was recommended for a Victoria Cross, but received a bar to his DSO instead in September 1918. “A brilliant squadron leader of exceptional daring who has destroyed fifty-one enemy machines,” begins the citation for that honour.

Collishaw was nominated for another VC, but it also was downgraded, it’s believed, partly for political reasons—because he flew for the Royal Navy Air Service and not the Royal Flying Corps.

Frenzied fighting at war’s end raised the total of Collishaw’s confirmed victories to 60.

“I consider Major Collishaw one of the Best Squadron Commanders in the R.A.F.,” wrote Duncan Pitcher, commander, 1st Brigade, RAF. “He showed the greatest tact and power of command [and] set a very fine personal example of flying courage in aerial fighting.”

Promoted to lieutenant-colonel on Oct. 1, 1918, Collishaw returned to Britain where he helped lay the groundwork for the Canadian Air Force, created in 1920 (renamed the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1924).

A Hawker Hurricane Mark II D of No. 6 Squadron RAF, based at Shandur, Egypt, circa 1942. [IWM/Wikimedia]

When he returned to Britain, he was asked to command No. 47 Squadron, RAF, which was going to Russia in 1919 to support the White Russian forces fighting the Bolsheviks. He led (and flew with) the unit, which operated from specially equipped rail cars. Partially disassembled aircraft were transported where needed, then reassembled to fly from hastily built aerodromes.

Collishaw had three close calls in Russia. He nearly died of typhus, survived a deliberate train crash that crushed eight cars, and once had to taxi more than 30 kilometres overland to friendly territory after his aircraft was damaged in an attack.

He was awarded the Order of the British Empire and, from the Russians, the Order of St. Vladimir, the Order of St. Anne and the Order of St. Stanislaus.

In the early 1920s, Collishaw spent three years commanding No. 30 Squadron, which provided air support protecting British interests in Persia (now Iran), then returned to England for his long-postponed wedding.

“I consider Major Collishaw one of the Best Squadron Commanders in the R.A.F. He set a very fine personal example of flying courage in aerial fighting.”

He subsequently helped develop the RAF fighter force, served aboard the aircraft carrier Courageous, and was promoted to wing commander, group captain and, on the eve of the Second World War, air commodore commanding Egypt Group, responsible for defence of Egypt and the Suez Canal.

Collishaw soon realized his resources were too limited to do all that was expected. When war was declared in September 1939, the Italians had nearly 400 aircraft in North Africa. The Allies had only 150, and those were mostly outdated biplane fighters and bombers—and one Hawker Hurricane.

He ordered raids of Italian airfields and made the most of his single Hurricane fighter, duping the Italians into thinking he had a much larger force by ordering many single plane attacks and constantly moving the Hurricane from base to base. Italian fuel was wasted and manpower was diluted as their fighters were spread across North Africa and ordered to maintain patrols.

No. 204 Group, eight squadrons boasting Hurricanes and Lysanders, was created in April 1941 and Collishaw, in command, developed an innovative tactical system of close air support to attack ground targets that was adopted by the RAF and the U.S. In 1941, he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath.

Collishaw surveys the ruined buildings on the airfield at El Adem, Libya, following its capture on Jan. 5, 1941, during the advance on Tobruk. [Hensser H/IWM/CM399]

The argument came to a head when British Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder became commander of the RAF in the Middle East. His and Collishaw’s leadership and personality styles clashed. The reserved Tedder preferred meticulous planning and control, while the exuberant Collishaw had cut his teeth before radio and radar, when pilots had much more independence. In 1941, Tedder took over No. 204 Group from Collishaw.

By the time Collishaw left Egypt, his crews had destroyed about 1,100 Italian aircraft. But he was criticized for lack of support of the unsuccessful ground campaign to end the German siege on Tobruk, Libya. In summer 1941, he returned to Britain.

In March 1942, Collishaw was promoted to air vice-marshal and put in command of 14 Fighter Group in Scotland, responsible for the defence of Scotland and the navy base at Scapa Flow.

He retired in 1943 after a career of nearly 30 years. He served as a liaison officer with the British Civil Defence Service until the end of the war. In 1945, he returned to Canada, where he was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in 1974, two years before his death in Vancouver. In 1999, B.C.’s Nanaimo-Collishaw Air Terminal building was named in his honour.

“I feel that my days of command in North Africa, when we had to depend upon superior strategy, deception and fighting spirit, faced with a numerically superior enemy, represent by far my best effort,” Collishaw said later in his life.

“Yet if I am known at all to any of my fellow Canadians it is through more carefree days, when as a fighter pilot, with the limited responsibilities of a flight commander of a squadron over France, I had the good fortune to shoot down a number of the enemy without in turn being killed.”

Advertisement