It concealed escape

tools and was designed

to transform into an

ordinary shoe

When Erin Napier is asked about her favourite item in the collection of the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in Hamilton, Ont., the curator produces a pair of well-worn leather boots, originally property of Second World War Lancaster flight engineer James Allward.

These high-top flying boots look ideal for their primary use—keeping aircrew warm as they carried out their missions over wartorn Europe.

But they have a split personality.

“This is a regular, everyday thing that can be used as an escape item,” she explains. “If an airman had bailed out or survived a crash, he could use a knife concealed in the fleece lining and cut the leather upper off. He’d be left with just a regular looking shoe”—and not distinctive footwear that could raise unwanted questions. The top sections could also fit together to form a warm vest. Later designs included hollow heels for secreting escape kits and laces that could be used as Gigli saws, with magnetized tips that could serve as compasses.

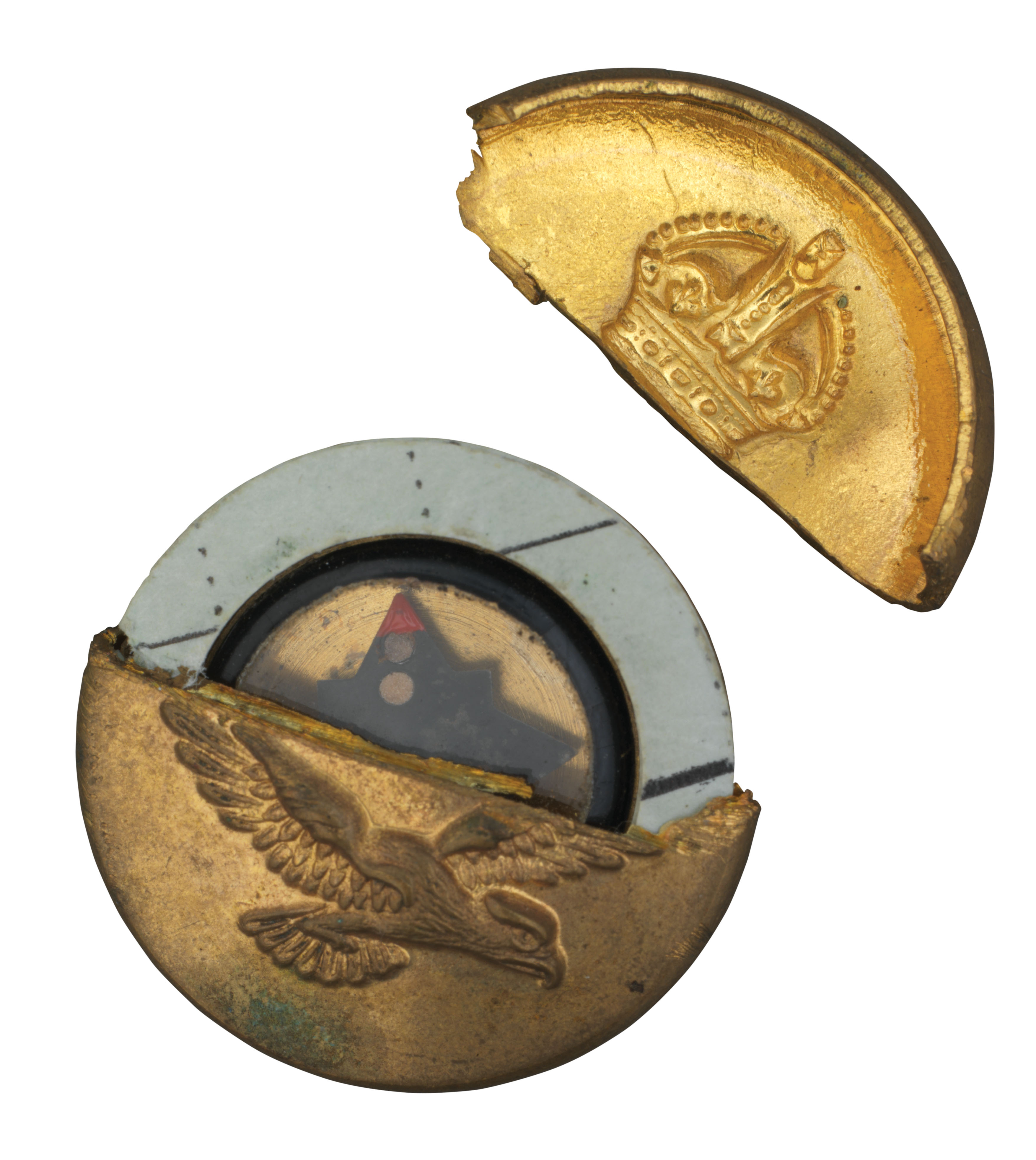

Compass in a button: Miniature compasses were hidden inside uniform buttons. To foil discovery, the buttons unscrewed backwards. [Imperial War Museum]

“By 1943, Allied air force officials believed that if a crewman landed by parachute in occupied territory, he had a 50 per cent chance of getting home safely.” — Major-General David Zabecki

The boot was the brainchild of Major Christopher (Clutty) Clayton Hutton. Britain’s War Office capitalized on his pre-war interest in show-business escape artists by employing him as a “deception theorist” with the British Directorate of Military Intelligence, Section 9. MI9 developed items to aid downed aircrew and prisoners of war to escape through hostile territory and evade capture. By the end of the war, British aircrews carried a Hutton-designed escape kit the size of a cigarette pack, containing food, currency, razor blades, water purifying tablets and a water bottle.

Sharp idea: Razor blades were magnetized to serve as compasses. Suspended from a string, or floated on water, the arrows pointed north. [EPH2217]

MI9 developed items to

aid downed aircrew and

prisoners of war to escape.

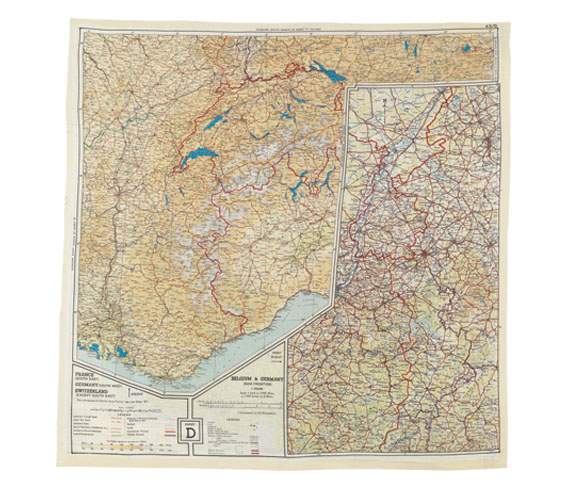

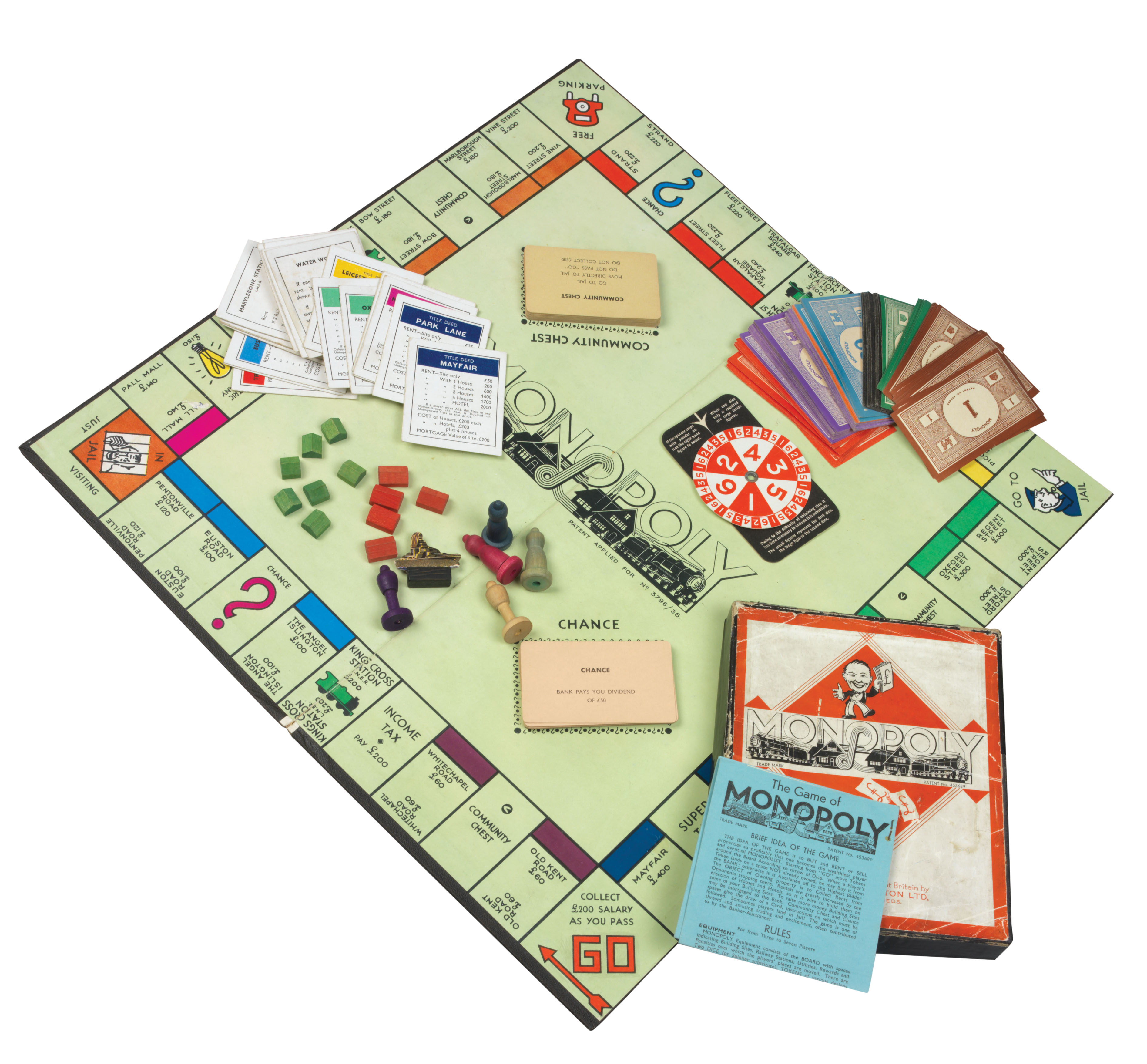

Care packages from non-existent charities were delivered to PoWs, containing Hutton’s extra gifts: maps printed on silk, disguised as handkerchiefs or hidden inside chess pieces, game boards or phonograph records; a cigarette-holder telescope; miniature compasses hidden in pens, pencils and buttons; spare uniforms that could easily be converted into civilian clothing, with maps printed on them in invisible ink. All but one of the deceptions were eventually discovered; the exception was specially marked Monopoly game boards concealing escape kits, including tools, local maps and currency.

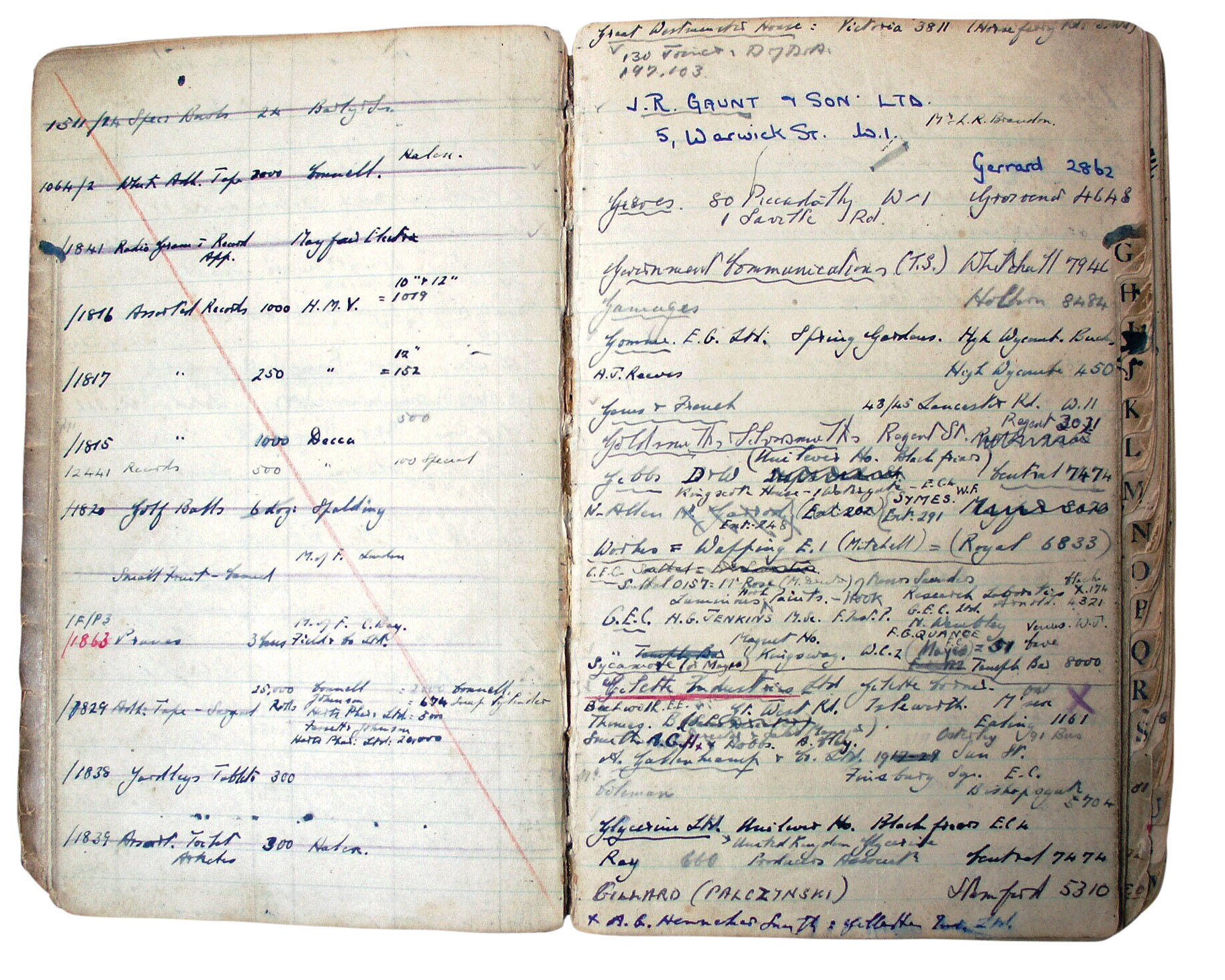

Charles Fraser-Smith’s notebook records more than 300 firms that manufactured everyday items in which maps and escape tools could be secreted.

It has been estimated that about half of the 30,000 British and Allied troops who successfully escaped enemy territory had been equipped with MI9 maps and escape equipment.

Silk escape maps did not crease, could be scrunched into tiny spaces and made no noise when in use. [19900076-505;]

“By 1943, Allied air force officials believed that if a crewman landed by parachute in occupied territory, he had a 50 per cent chance of getting home safely,” writes U.S. military historian Major-General David Zabecki. As many as 200,000 escape attempts were made; while most were unsuccessful, valuable enemy resources were used hunting down escapees, the morale of people in occupied Europe was bolstered in aiding escapees, and aircrews’ confidence was boosted by their comrades’ much-celebrated returns.

Operation mincemeat : A postwar film was based on the planting of phoney plans on a dead body, which successfully duped the Nazis into believing the Allies intended to invade Greece, not Sicily.

Evading detection was also of vital interest to spies, who had their own champion designers, including Charles Fraser Smith, who invented “Q gadgets” for the Special Operations Executive and is widely credited as the inspiration for Q, the quartermaster in James Bond films. Smith’s canny gizmos include cigarette lighters containing miniature cameras, shaving brushes containing film, maps and saws secreted in hairbrushes and an asbestos-lined pipe for carrying secret documents. He was also famously involved in an operation in which a body carrying false papers was dropped off the Spanish coast, misleading the Nazis about the invasion of Italy. The ploy was immortalized in the book and film, The Man Who Never Was, and the recent BBC series “Fleming: The Man Who Would Be Bond.”

Monopoly game boards sent to prisoners of war were extra thick. Dots on the playing surface guided prisoners to maps, escape tools and local currency hidden between the layers.

Advertisement