Legion Magazine sat down with Tim Cook, author and historian at the Canadian War Museum, to discuss the introduction of gas warfare in the First World War and the invention and evolution of Gas Masks used to save the soldiers’ lives.

The first gas mask issued to British troops after the Germans unleashed the devilish new weapon in 1915 was devised by a doctor from Newfoundland.

On April 22, 1915, German troops on the Western Front released 160 tonnes of chlorine gas, which turned into a yellow-green cloud six kilometres long and half a kilometre wide. It drifted on the wind over Canadian and French lines and, heavier than air, settled in low areas—turning trenches into death traps.

When chlorine contacts moisture in the eyes, nose and lungs, it turns to an acid that blinds, burns and blisters. It destroys lung tissue; victims drown in their own body fluids or die of asphyxiation. There is no antidote.

Back then, no one was prepared. Men began hacking and coughing after breathing the bleach-scented gas. Many died, others were blinded and burned; most survivors suffered lifelong lung problems.

Canadian artillery officer Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Morrison was horrified to see men “literally coughing their lungs out,” later to “roll about like mad dogs in their death agonies.”

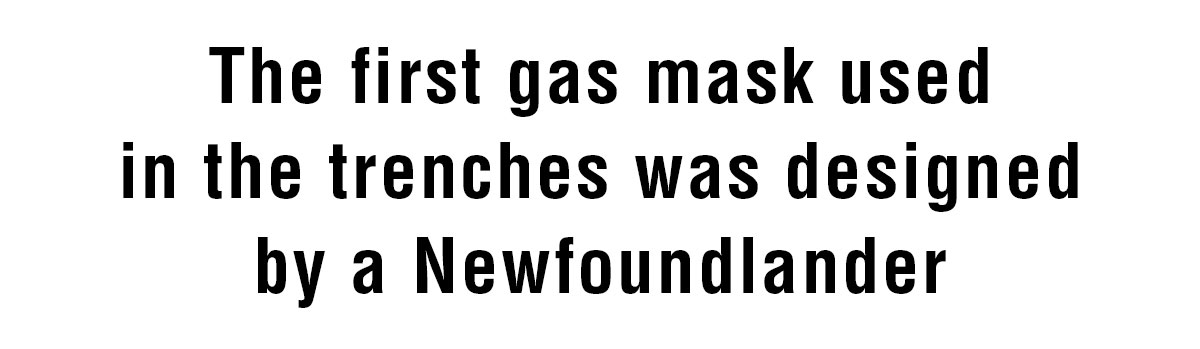

A soldier wears an early gas mask for protection from poisonous clouds. [Legion Magazine Archives/19700140-077]

In the second attack two days later, Canadian troops were told to hold a handkerchief or sock wet with water or urine over their noses so the chlorine would crystallize there before reaching the lungs.

On May 3, the British issued 30,000 gauze-wrapped cotton pads, which were dunked in bicarbonate of soda, then held over the nose and mouth. Goggles were issued to protect the eyes. This was improved by the the Black Veil respirator, which featured a string to hold the pad in place.

It wasn’t enough. By June 6, British and Canadian soldiers were issued the first gas mask—hood, actually—designed by Captain Cluny Macpherson, medical officer of the 1st Newfoundland Regiment.

“The men surely do look a weird sight when they are wearing them. Great goggle-eyed things like a false face.” — Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan E. MacIntyre, 28th Battalion. [Clifford M. Johnston/LAC/PA-056171]

Macpherson suggested covering the whole head in a flannel bag soaked in a chemical mixture rendering it impervious to gas. The Hypo helmet, known as the British Smoke Hood, had a visor of mica or cellulose acetate. It was fragile and caused headaches, likely from a build-up of carbon dioxide, but it was a start.

It was followed by a hood with eyepieces and a valve through which troops exhaled. It was described as the “goggle-eyed bugger with the tit.” Macpherson continually improved his designs, even after he returned home, his attention turning from soldiers to miners’ lung problems, said Maureen Peters, curator of The Rooms in St. John’s.

Two years into the war, all sides were using artillery shells containing gas, and more and more sophisticated gas masks were developed in response to continual development of lethal vaporous threats.

By war’s end, troops were issued the small box respirator, which decontaminated poisoned air. [CWM/19720102-061]

On July 12, 1917, the Germans began using mustard gas, which did not need to be inhaled to be lethal—this colourless, oily vapour can be absorbed through the skin. It stripped the mucous membranes in the lungs and stomach, causing internal bleeding. Its long-lasting pollution of soil, mud, water and clothing continued to claim victims from secondary poisoning for weeks after attacks.

This gas rattle was one of the noisemakers that warned troops of chemical attacks. [CWM/19880212-107]

By 1917, the small-box respirator had been developed and distributed to British and Canadian troops. Air was drawn through a filter box and decontaminated before passing into the face mask.

Troops cursed gas masks. Regardless of design, they were uncomfortable and cumbersome. But they were also thankful for them.

Advertisement