A soldier walks past No. 1 Canadian Field Hospital in Al Qaisumah, Saudi Arabia, on Feb. 11, 1991. [DND/REC92-1558]

As a private with Charles Company, 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, Schutt processed and guarded thousands of Iraqi prisoners during the 1991 Gulf War, all while facing the prospect of a biological or chemical attack.

“We took the plague and anthrax vaccines without them ever being trialled on human beings,” said Schutt, now a nickel miner in Sudbury, Ont.

“I asked the base surgeon: ‘What are the long-term effects of this?’ And she said: ‘I’m not going to lie to you, we don’t know. They’ve never been trialled on anybody; we don’t have any idea if these vaccines will have a long-term effect.’

“She said: ‘They could take 10 years off your life, for all I know. But all I do know is that they could save your life tomorrow.’”

Today, there is concern in some quarters about the newly developed inoculations designed to end the pandemic. The fear is that the vaccines have rolled out too quickly 10 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, when vaccine development can usually take up to 10 years or more

Experts insist the speed is not a product of shortcuts, but instead a combination of multitasking, unprecedented global coordination and the fruits of earlier research.

Understanding this is a matter of public health concern, Kerry Bowman, a University of Toronto bioethicist and environmentalist, told CTV News in December. Bowman’s work on emerging zoonotic diseases involved him in research and health care during the Ebola virus and SARS outbreaks.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes the COVID-19 disease isn’t the first coronavirus. Human coronaviruses were first identified more than 50 years ago with the HCoV-229E, which infects humans and bats. Scientists have since discovered five others, including MERS-CoV, which causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and SARS-CoV, the first strain of the SARS coronavirus species that led to the current pandemic. The groundwork was not for nothing, said Bowman.

“Because we’ve got this pattern of emerging infectious diseases…many good people have been on to this and developed a research platform that was tremendously useful when this COVID-19 pandemic struck,” said Bowman.

“They really weren’t starting from ground zero at all. We built on previous lessons tremendously and now we’re going to soon reap the benefits of that.”

In a December survey of 1,605 Canadians, 48 per cent of respondents told the Angus Reid Institute they would be willing to get the shot immediately. Another 31 per cent said they would get it after a wait. Still, 14 per cent said they would not get the shot and seven per cent weren’t sure.

You couldn’t deploy if you didn’t get those vaccinations.

In comparison, the figure is more positive than the 39 per cent of American respondents who told the Pew Research Center in January that they definitely or probably would not get vaccinated.

Now time is of the essence in increasingly critical ways as more contagious strains of the virus begin to emerge in North America.

Guards screen vehicles at the main entrance to the “Canada Dry 2” base in Qatar on Feb. 21, 1991. [DND/ISC91-5368]

“You couldn’t deploy if you didn’t get those vaccines,” said Schutt, who says he doesn’t know if his pancreatitis is related to his service. “So myself and every one of those soldiers who took those vaccines without them ever being trialled did it for our country.”

Schutt describes them as the first Canadians deployed to a war zone who didn’t stand next to their allies on the front line—an ignominious distinction which he says makes him sad.

The navy, air force and army were all sent to the Gulf, a total of about 5,100 personnel. Some 530 personnel staffed a Canadian field hospital in Al Qaisumah, Saudi Arabia, caring for both coalition and Iraqi wounded.

Canadian soldiers guarded hospitals and PoWs, watched over the airfield at Doha, Qatar, and cleared landmines and unexploded ordnance during and after the short war.

In 1991, Iraq had the fifth-largest army in the world, with more than a million men in uniform. Three-quarters of Iraqi males between ages 15 and 49 were conscripted; only a third of the Iraqi army were skilled professional fighters.

Saddam’s invading forces numbered 120,000. It took his troops just two days to conquer Kuwait in August 1990, after which Saddam boosted his occupying force to 300,000.

The subsequent coalition offensive, launched on Jan. 17, 1991, was devastating: 25,000 to 50,000 Iraqi troops were killed, more than 75,000 wounded, and 80,000 captured. Some 3,300 Iraqi tanks were destroyed, along with 2,100 armoured personnel carriers, 2,200 artillery pieces and 110 aircraft. Nineteen Iraqi ships were sunk and six damaged.

On Feb. 23, 1991, after just two days in-country, Charles Company, 1RCR, deployed forward into the desert 30 kilometres south of the Saudi-Kuwait border, where it joined the Forward Surgical Units of 1 Canadian Field Hospital and the British 32nd Field Hospital. The soldiers assumed established perimeter patrols, gate guards and roving pickets while assisting in the setup of the rest of the Canadian hospital.

The ground war started the following day, and the first casualties began arriving from the front less than 18 hours after the Canadians had taken up their new post.

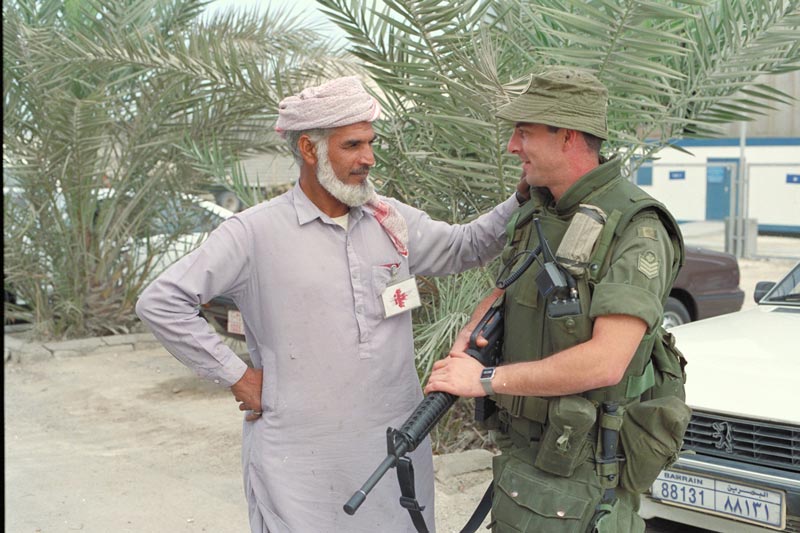

Sergeant Dan Potvin chats with a civilian while on sentry duty at the Canadian military headquarters in Bahrain on Jan. 13, 1991. [DND/ISC91-4119]

The cases ranged from simple dehydration to profound head wounds and severed limbs. The company would soon assume duties escorting and guarding captured Iraqi soldiers at a British prisoner of war camp a few kilometers away. It was built for 8,000, said Schutt, but it held many more, all outdoors behind high wire fences.

“They had all their life savings with them,” said Schutt, “in American dollars, in Deutschmarks, in Canadian dollars—in every currency you could imagine, because they were told if they were wounded that, because of the American health-care system, they would have to pay for their treatment. They were a sad lot.”

The prisoners would arrive in groups of 60 by helicopter, usually Chinooks, after which they were herded into a holding pen and searched, said MacLean. They were then examined by medical teams and documented. Most were malnourished, dehydrated and demoralized. Many had no socks or shoes.

“All wore a look of total defeat that was more disturbing than even the most menacing growl.”

The conscripts were easily distinguishable from the soldiers of Saddam’s elite Republican Guard, said Schutt. The conscripts, he explained, “were in whatever shape they were drafted in; the Republican Guard guys, they looked at you with hate in their eyes.”

The threat of neurological, biological or chemical warfare dictated that the prisoners’ hands could not be bound. Commands were limited to hand signals, explained MacLean in an account he wrote for the regimental newsletter—not only because of the language barrier, but quiet captors meant for calm captives.

“Our system was so efficient, in fact, that when the British resumed their duties, they adopted the Charles Company search and handling techniques,” wrote MacLean.

Private Alain Maréchal cleans his weapon at the Royal 22nd Regiment headquarters at the “Canada Dry 2” base in Qatar on Feb. 25, 1991. [DND/ISC91-5406]

The Canadians returned to the field hospital after the shooting stopped and the flow of PoWs abated. On March 20, 1991, they returned home, their bags and clothing reeking of oil from the burning wells that Iraqi troops ignited on their retreat.

Schutt, who also served in Cyprus (1989-90) and Yugoslavia (1994-95), now operates a specialized bucket loader in a nickel mine.

He says the most important message he can impart in these times is that soldiers didn’t think twice about taking vaccines they trusted could save their lives, nor should Canadians now. He even suggested an ad campaign on the theme, leaving a message at his MP’s office.

“Nobody called me back,” he said.

___

For more on Canada’s role in the liberation of Kuwait, read “Gulf War Aftermath” in the March/April 2021 issue of Legion Magazine, on newsstands now.

Advertisement