In a U-boat rampage off the East Coast in 1918, the schooner Dornfontein was captured and burned

On Aug. 3, 1918, a small boat carrying nine sailors arrived at Gannet Rock in the Bay of Fundy. They had a tale to tell.

The previous day, a submarine had stopped their schooner—looted it, and took the crew as prisoners. Then the raiders set the schooner on fire and turned its crew loose in their small boat. It had taken more than 12 hours to row to shore. It was not supposed to happen.

When the First World War started in 1914, submarines were a novelty weapon. Their range was short and everyone expected them to operate inshore, fully submerged and, in accordance with international law, to sink only warships. After all, submarines did not have enough crew to take ships as prizes, or space for prisoners, or—in the German case—the ability to bring captured ships home as prizes of war.

Certainly they presented no threat to Canada, if only because they could not cross the Atlantic. So Canada sent troops to the Western Front and the British promised to protect Canada from whatever naval threat developed. No one expected much.

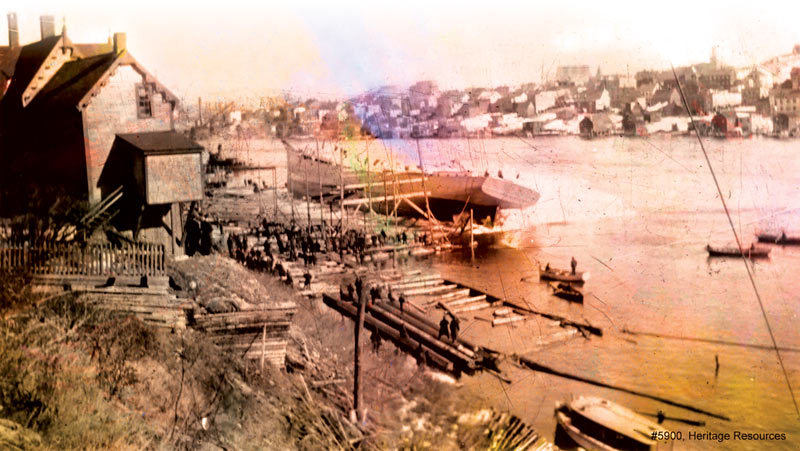

On its maiden voyage, the four-masted schooner was carrying a heavy load of wood to Natal, South Africa. [Marc Milner]

However, the establishment of a “distant blockade” of Germany by the Allies in 1914, by closing off the Strait of Dover and the passage between Scotland and Norway, gave the Germans an opening. To be lawful, a blockade had to be right along the enemy coast. The Germans responded in early 1915 with a “blockade” of Great Britain by submarines, threatening to sink warships and merchant ships on sight. With that, the U-boat war on Allied merchant shipping began in earnest.

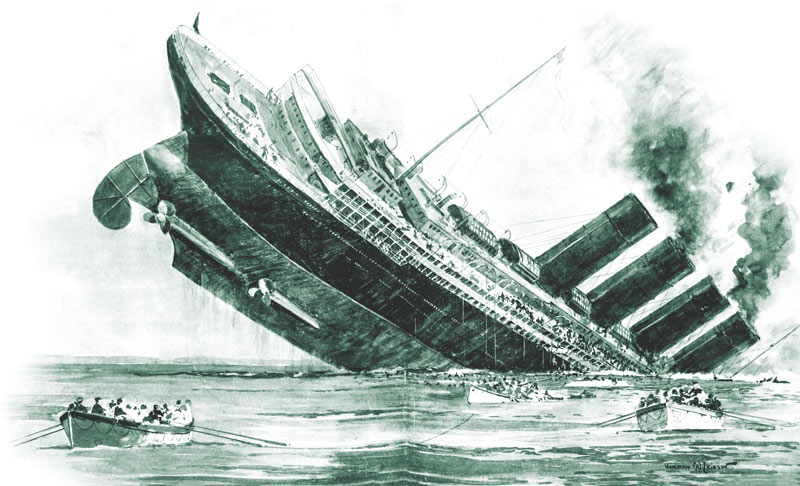

The sinking of RMS Lusitania by a U-boat in May 1915, with a heavy loss of life (many American), brought enough international pressure to end the first unrestricted campaign. The pattern repeated itself in 1916, when neutral pressure stopped another unrestricted U-boat campaign.

In the meantime, Germany’s U-boat fleet grew in size, power and range, including a program of “U-freighters” to evade the Allied blockade. In July 1916, the 1,600-tonne U-Deutschland arrived at Baltimore, Maryland, to load cargo. (The second U-freighter, U-Bremen, was lost at sea on its maiden voyage).

Clearly, U-boats could cross the Atlantic. More alarming was the arrival in October of U-53—a 740-tonne combat submarine—at Newport, Rhode Island, which promptly sank four British vessels just outside American waters. By the end of 1916, the shooting war had come to the western Atlantic.

As 1918 dawned, the Canadian coast was largely undefended.

Germany declared another unrestricted submarine campaign against the Allies in February 1917. They expected the Americas to declare war, but believed they could not intervene decisively in Europe for years. And if Germany could sink more than 800,000 tonnes of British shipping a month over the next six months, Britain would capitulate. The 1917 U-boat campaign was a gamble, but one worth the risk.

The British beat the U-boats by introducing convoys in the summer of 1917, but the subs kept the Royal Navy fully engaged in European waters for the rest of the war.

Canada was left to fend for itself—with some important help from the Americans. By 1917, the Royal Canadian Navy had 20 small ships and 12 Battle-class trawlers armed with puny 12-pounder guns at best. As 1918 dawned, the Canadian coast was largely undefended.

RMS Lusitania, bound for Liverpool from New York, was sunk by a torpedo from U-20 on May 7, 1915. [Wikimedia]

The U-boats arrived in the summer of 1918. U-151 was already in U.S. waters when U-156 reached Cape Race, Nfld., in early July. It sank a couple of Norwegian schooners and then headed for New York.

After dropping mines, which sank the cruiser USS San Diego on July 19, U-156 turned back north. In broad daylight—and just five kilometres away from vacationers on the beach at Cape Cod—the U-boat leisurely sank four barges and damaged their tug with gunfire. News of the attack off Cape Cod reached Canada just as the fishermen came ashore in Canso to tell their story.

The nine crew members were taken aboard the sub while the schooner was looted.

The next day, July 26, U-156 attempted to sink two British freighters south of Cape Sable, N.S. News of these attacks reached Ottawa on July 27.

The presence of U-156 in the Bay of Fundy makes it difficult to explain what happened next.

On July 31, the 695-tonne four-masted cargo schooner Dornfontein cleared Saint John, N.B., on its maiden voyage with a load of lumber for Natal, South Africa. Highly classified routing instructions issued before departure were supposed to keep it safe. These were usually kept in a weighted bag, ready to throw overboard should the enemy appear. Other than that, Dornfontein was on its own.

By the afternoon of Aug. 2, Dornfontein was about 60 kilometres south of Grand Manan Island when U-156 rose from the depths and fired two shots across the bow. Dornfontein hove to. The nine crew members were taken aboard the sub while the schooner was looted for food (it carried six months of supplies), the seamen’s clothing, other valuables—including Dornfontein’s secret instructions—and gasoline.

Within a month of launch, Dornfontein was seized, looted and burned by a U-boat crew 10 kilometres south of Grand Manan Island in the Bay of Fundy. [Heritage Saint John]

The Canadians were held on the U-boat for five hours, interrogated and fed a meal of bully beef and rice. Nearly all the German crew spoke English and one lieutenant claimed to have vacationed annually on the Maine coast for decades.

Dornfontein’s captain described the Germans as “a beastly looking set of fellows….” The presence of blueberry pie on the mess table seemed suspicious, and seaman James Oliver of New River, N.B., protested that the food was probably poisoned. What happened next is unclear, except that Oliver was shot in the leg.

The cheery calls of “Goodbye!” and “Good luck!” from the Germans were bitterly ironic for Dornfontein’s crew as they set off for Grand Manan that afternoon. As they rowed away, their ship was ablaze from stem to stern.

At 6 a.m. the next day, Dornfontein’s crew scrambled ashore on Gannet Rock and, later that day, rowed the short distance to Grand Manan, where they were met by the RCN and taken to Saint John. The men provided details of U-156’s size, armament and crew.

The signal to Ottawa read in part, “Submarine two hundred and seventy feet long, able to submerge in twenty seconds. Engine room plates marked U fifty-six. Vessel painted black on top, grey underneath, old paint….”

More alarmingly, the report noted that “All papers taken.” A board of inquiry found the schooner’s captain “gravely negligent” and suspended his master’s licence for the rest of the war.

Meanwhile, U-156 headed for the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, sinking more fishing schooners and then the 4,900-tonne British tanker Luz Blanco in a running gun battle off Halifax.

On Aug. 20, the Germans captured the Canadian steam trawler Triumph, which they armed with one or two 3-pounder guns. Triumph was a familiar sight, and it had no problem getting close. After sinking four schooners off Canso, U-156 and the hijacked Triumph headed for the fishing grounds south of Newfoundland.

The Canadian navy could do little. Its ships were too small, too slow, too poorly armed and too few to either trap the big subs or fight them. Evidence of that was soon clear. On Aug. 25, one section of an RCN patrol, HMCS Hochelaga and Trawler 22, caught sight of a schooner’s masts falling and went to investigate: they found U-156 lying on the surface. Instead of attacking immediately, the Canadians ran away. By the time the whole patrol—Cartier, Hochelaga and two trawlers—returned to the scene, U-156 was long gone and soon on its way home. The captain of Hochelaga was dismissed from the service for failing to use “his utmost exertion to bring his ship into action.”

To provide the RCN with a safe refuge, the Halifax fortress was fully manned until the end of the war.

Dornfontein burned to the waterline but was salvaged. It sailed again under the American flag as Netherton until it was abandoned at sea—on fire—in August 1920. James Oliver limped for the rest of his life. And U-156 never made it home.

—

The life of U-156

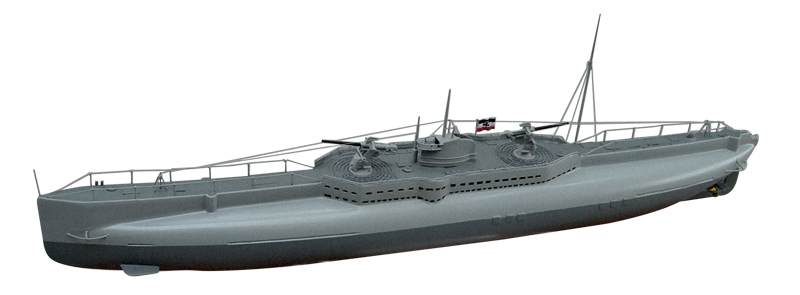

The Imperial German Navy sub U-156 sank 44 ships before it was lost in the Northern Barrage minefield between the Orkney Islands and Norway. [SDMODELMAKERS]

During the Great War, the Germans built 373 U-boats, most of them small and intended for European waters. But a portion were large, displaced up to 1,000 tonnes, and were capable of long-range patrols.

The biggest, however, were the five remaining U-freighters which the Germans converted into warships in 1917. These submerged cruisers were the largest submarines in the world, over 60 metres long with a cruising radius of 49,000 kilometres and full displacement weight of over 2,200 tonnes. Just one of these monsters, like U-156, carried more firepower than the entire RCN: two 15-centimetre deck guns, two 88-millimetre guns and 18 torpedoes.

The U-cruisers were a law of the sea unto themselves.

U-156 was commissioned at Bremen, on the Weser River about 60 kilometres from the North Sea, on Aug. 28, 1917.

Its first voyage was to the Canary Islands to load contraband. The British learned of this effort to breach the blockade and sent a sub to ambush U-156. A torpedo from a British sub hit U-156, but failed to explode. The U-boat escaped.

The sub’s only cruise operation began on June 15, 1918, when Captain Richard Feldt and his crew of 76 set off for Long Island, N.Y. Over the next nine weeks, U-156 accounted for approximately four small steamers, three trawlers, 19 fishing schooners, two very large sailing ships, one tanker, four barges and a U.S. Navy cruiser.

U-156 did not escape retribution. The Allies laid deep minefields at the entrances to the North Sea to sink U-boats slipping through. Signals sent by Feldt in the final approaches gave precise timing and routing for his passage through the Northern Barrage. When U-156 failed to report in on Sept. 25, it was assumed that it had struck a mine and sunk with all hands. It carried to the grave the other side of one of the most fascinating stories of Canada’s Great War.

Advertisement