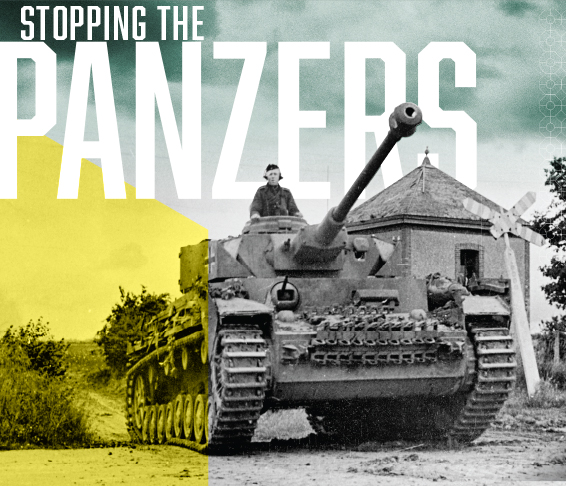

A German tank commander stares down a photographer in Normandy in June 1944. His Panzer IV-G tank has 80mm frontal armour; some 8,500 Panzer IVs were built during the war. [LAPI/Roger Viollet/Getty Images/14089-9]

The problem with the well-known story of Canada’s role in Operation Overlord, the D-Day landings in France in June 1944, is not what it says, but what it leaves out—just about everything that matters.

In the long-familiar tale, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, supported by amphibious tanks of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, landed on Juno Beach. It was a tough beach assault, but the landing went well. By the end of the day, Canadians made the deepest penetration of any Allied division. The next day, Canadians cut the critical Caen-to-Bayeux road and rail link—our signal accomplishment. Further advances were thwarted by fierce German counterattacks, and the Canadians stalled for a month while the British and Americans on either flank got on with winning the Normandy campaign.

Allied commanders of Operation Overload meet on Feb. 1, 1944: (front, from left) Royal Air Force Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, U.S. Army General Dwight D. Eisenhower, British Army Gen. Bernard Montgomery; (rear, from left) U.S. First Army Gen. Omar Bradley, Royal Navy Admiral Bertram Ramsay, RAF Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory and U.S. Army Lieutenant-General Walter Bedell Smith. [Frank L. Dubervill/DND/LAC/PA-129050]

The first critical impact of the Canadian Army on Operation Overlord was its key role in the initial planning. In 1943, when British Lieutenant-General Frederick Morgan was appointed Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander and tasked with planning the invasion, First Canadian Army was central to his whole scheme. The plan called for a three-division landing north of Caen—one American, one British and one Canadian—under command of the British Second Army. First Canadian Army—supported by the fighters of No. 84 Group, RAF—was to arrive soon after the initial landing as the break-out force. Morgan’s plan was accepted by the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff in July 1943.

Decisions made at the Quebec Conference of August 1943 changed Morgan’s plan. Under the new scheme, First United States Army would command the initial landings. First Canadian Army’s exploitation task remained, and the British Second Army was relegated to a follow-on role. So, in the fall of 1943, Overlord was planned to be a North American-led operation.

Politics then conspired to unseat First Canadian Army from its central role in Overlord. By 1943, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s Liberal government was under mounting pressure from the electorate to get the Canadians fighting, like everyone else. Instead, Canadian soldiers languished in garrisons in England, waiting for their big day. The government blamed the commanding officer of First Canadian Army, General Andrew G.L. McNaughton, for resisting offers to send Canadians troops to combat theatres. It did not help that the Minister of National Defence, Colonel J.L. Ralston, hated McNaughton, while many senior Canadian officers also wanted him gone.

In fact, King and Ralston had to press hard to insert 1st Canadian Division and 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade into the landings in Sicily in July 1943, but that brief campaign brought little respite from public unrest. When Ralston approached the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Alan Brooke, in July about getting rid of McNaughton, Brooke warned that the only way to do so was to break up his army.

Sitting on an M10 tank destroyer aboard a Rhino ferry, members of the Royal Canadian Artillery approach Bernières-sur-Mer, France, on June 6, 1944: (from left) Gunner B. Long, Bombardier M.B. Farrell, Gunner C. Henderson, Sergeant G.A. Chappel, Lieutenant W.E. Lee and Gunner M. Dowhaniuk. [Ken Bell/DND/LAC/PA-137523]

In the fall of 1943, McNaughton remained content to command a joint Anglo-Canadian army in the breakout role. For Brooke—indeed for the British government—this was intolerable, and so Brooke continued to work with Ralston through the fall to remove McNaughton. When this was finally accomplished in early December (on medical grounds), First Canadian Army was not only broken, it was now rudderless. Britain’s I Corps absorbed 3rd Canadian Division for the invasion and any chance of a high-profile Canadian role in Overlord was gone.

In any event, it is doubtful that a lead role for Canada in Operation Overlord would have survived. When General Bernard Montgomery and General Dwight D. Eisenhower assumed command of Overlord, they dismissed Morgan’s plans and adopted a five-division assault with First United States Army and British Second Army landing side by side. First Canadian Army now became the follow-on force. Given the pressure of inter-Allied politics and the ultimate importance of the landings to the prestige of Great Britain, Operation Overlord could never have been an American-Canadian operation.

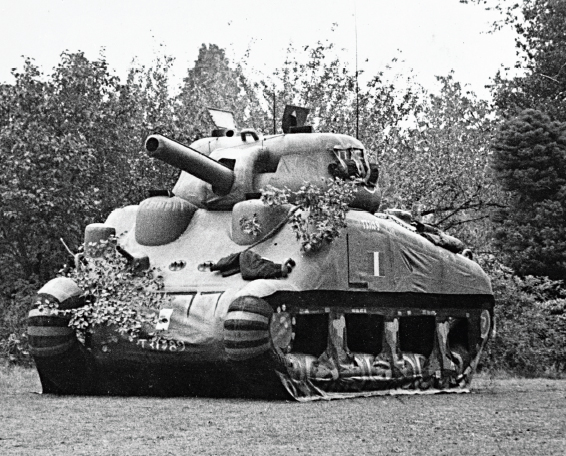

The second critical Canadian impact was that First Canadian Army did not fade from the Overlord picture. It appears that the Germans were watching them as an indicator of Allied intent—as they had in the Great War. So, the Canadians played a key role in Operation Fortitude, the D-Day deception that took place in early 1944. In fact, contrary to popular wisdom, American General George S. Patton was not visible in the initial phase of Operation Fortitude; First Canadian Army was the beating heart of that initial deception.

Part of the D-Day deception plan, Operation Fortitude included a fictitious army stationed in southern England and mimicking a large-scale invasion force aimed away from Normandy. This included inflatable tanks (below) and dummy landing craft. [Imperial War Museums/H 42531]

When the Normandy landings began on the morning of June 6, Germany’s immediate fear was that it was a feint and a prelude to main landings in the Pas-de-Calais and the Netherlands’ Scheldt River estuary.

First Canadian Army had been doing a staff work-up for a Scheldt landing—something the British had done in September 1914—since the summer of 1943. These efforts were supported by II Canadian Corps with amphibious training exercises in England’s muddy and tide-swept Medway River (conditions similar to the Scheldt) in the days immediately following D-Day.

On June 8, two days after D-Day, 2nd Canadian Division prepared all its vehicles for a landing. The next day, newspapers in Hamburg reported that a Canadian-British landing in northern France or the Scheldt was imminent. On June 10, in response to these reports, 1st SS Panzer Division and the Panzer regiment of 116th Panzer Division, already moving to the Canadian front in Normandy, were diverted to the Pas-de-Calais.

Patton was announced as the commanding officer of FUSAG on June 12. Until then, First Canadian Army had been the purveyor of the deception that fixed 15th German Army and much of the available armour in the Pas-de-Calais, more than 300 kilometres northeast of the Normandy beaches.

Members of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers work at waterproofing their Sherman tanks in England in April 1944. [Donald I. Grant/DND/LAC/PA-188676]

The origins of this lay in Morgan’s plans of 1943. Morgan and his staff identified two areas over which Germany might launch its Panzer divisions to destroy a landing between Caen and Bayeux. The first was northeastward from Bayeux along the flat, open crest of the Sommervieu-Bazenville ridge toward Courseulles-sur-Mer. The second was over the open countryside astride the Mue River northwest of Caen, which also culminated at Courseulles-sur-Mer.

In the three-division assault of the Morgan plan, 3rd Canadian Division was to hold the western end of the Sommervieu-Bazenville ridge. When Montgomery expanded the landings to five divisions, and included Sword Beach to the east, the Canadian assault was shifted to Juno Beach and the vulnerable Mue River area. This was where the major Panzer counterattack was now anticipated.

Only Germany’s Panzer divisions could repel the Allied landings. Lessons had been learned at Gela, Sicily, in July 1943, when the Americans were nearly driven into the sea by Axis armour, and later at Salerno, Italy, when Panzer Grenadier forces nearly achieved success. Two scenarios seemed likely for Normandy: a quick attack within days of the landings (like Gela and Salerno) to throw them back before they could get established, or a deliberate—and longer delayed—attack with more powerful forces. The commander of German coastal defences, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, favoured the quick attack, others preferred to let the Allies get ashore and then destroy them in a mobile battle. Either way, stopping the Panzers counter-attack was the key to securing Overlord.

As planning coalesced in early 1944, the critical nature of the Canadian role became clearer. The 3rd British Division and 6th British Airborne Division on Canada’s left were to secure Caen and the crossings over the Orne River and canal to prevent German armour using the great open plain north of Caen to roll up against the landings from the east. To Canada’s right, 50th British Division was to secure Bayeux and prevent its road hub being used to support armour on the Sommervieu-Bazenville ridge. If all this went according to plan, that left only the plains on either side of the Mue River open for a powerful German Panzer thrust to the sea.

If there was any doubt about German intent and the importance of the Mue River, Rommel’s intentions clear that up: he wanted four Panzer divisions ready to strike down the Mue River in May 1944. He very nearly got his wish: three were there on June 8.

The order given to 3rd Canadian Division for the opening phase of Operation Overlord confirms their role: stop the counterattack. The simplicity of the instructions issued to the Canadians in early March 1944 masked their significance. Instructions to defeat counterattacks were pretty generic by this stage of the war, but the context of this one is clear. While formations on either side of the Canadians were to secure their sectors against local counterattacks, including attempts by the Germans to recapture Caen or Bayeux, 3rd Canadian Division was to establish itself in fortress positions astride the Mue River around Carpiquet, Putot-en-Bessin and Bretteville-l’Orgueilleuse, and defeat the “probable” enemy counterattack.

As a result, 3rd Canadian Division landed as the single most powerful Allied formation in Operation Overlord: it came loaded up to defeat the Panzers. The Royal Canadian Artillery’s 12th, 13th and 14th field regiments and its 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, along with the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, brought to bear an enormous accretion of firepower.

The three field regiments, as well as the 19th Field Regiment attached for the assault, were all re-equipped with American M7 Priest 105mm self-propelled guns. This added enormous mobility, while the attendant command and observation-post Sherman tanks added the equivalent of an entire armoured regiment to the Canadian order of battle. In addition, three British artillery regiments were assigned to the 3rd Canadian Division, giving the division twice its normal allocation of field guns (144 instead of 72) plus 16 4.5-inch guns.

When all was said and done, 3rd Canadian Division wielded more firepower than any other Allied division in Operation Overlord—and they needed it. The final intelligence estimate on German tank strength, issued in late May, revealed that 550 German tanks were deployed between the Seine and the Loire rivers, and half of them were believed to be Panthers or Tigers. Worse still, 500 of these tanks were estimated to be in the sector of 1st British Corps around Caen. With the British—in theory—secure in Caen and along the Orne, the Canadians’ job was to stop these tanks from reaching the beach across the open ground west of Caen.

The assault and the days following it did not, of course, go precisely as scripted. The first major Panzer counterattack on 3rd British Division was launched by 21st Panzer Division late on the first day. It was seen off smartly, but the threat remained.

Thanks to Operation Fortitude, indecision about the meaning of the Normandy landings caused a delay in the deployment of 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth). When it arrived on June 7, its preparation for an attack to the sea west of Caen was pre-empted by the advance of 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade down the east side of the Mue River. A bloody and ultimately stalemated battle developed around Buron and Authie, which resulted in the Canadians abandoning the attempt to get to Carpiquet and settling for a fortress position at Villons-les-Buissons, north of Buron.

To the west of the Mue River, 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade had time to assume its fortress position around Putot-en-Bessin and Bretteville-l’Orgueilleuse on June 7. As 12th SS probed and prodded the Canadian line along the Caen-Bayeux highway on June 8, the elite Panzer Lehr Division—the second most powerful German Panzer division—deployed in front of 7th Brigade. The moment was ripe for a massive Panzer thrust to the sea, but the German high command fumbled it. By the time Rommel arrived on his first visit to Normandy—to the Canadian front on the Mue River—12th SS had not yet cleared the start line for the attack. It was decided to wait for 1st SS Panzer Division and the Panzer Regiment of 116th Panzer Division to arrive before launching the assault to the sea.

In the meantime, Panzer Lehr was shifted west to stop the British drive south from Bayeux, and 12th SS was ordered again to clear the Canadians out of their fortresses.

As 12th SS launched more futile attempts to dislodge the Canadians, word was received of an imminent (but false) Anglo-Canadian landing in the Pas-de-Calais or the Scheldt. 1st SS Panzer and the tanks of 116th Panzer Division were diverted to the northeast to meet the new threat, and the Panzer counterattack was postponed indefinitely.

The Canadian Army could never have won the Normandy campaign by itself, but it was certainly critical to Operation Overlord’s success.

Infantrymen from the Canadian Infantry Brigade examine a disabled Panzer V tank near Authie on July 9, 1944. [Harold G. Aikman/DND/LAC/PA-114367]

Advertisement