Australian soldiers use duckboards to pass through Chateau Wood, near Hooge in the Ypres Salient on Oct. 29, 1917.

[Frank Hurley/Australian War Memorial Collection/E01220]

A centennial project of the In Flanders Fields Museum, they trace the near-encirclement of the town and delineate the furthest point of advance by invading German forces (red) and the corresponding Allied (blue) front lines through five major battles around what was then known, and is forever remembered, as Ypres.

Some of the opposing ribbons are hundreds of metres apart; a few are barely a stone’s throw, reflecting the alienation and the intimacy of history’s first industrialized war more than 100 years ago.

In the Tyne Cot Cemetery at a former barn site outside Zonnebeke, 8,369 of the 11,968 graves belong to unknown soldiers.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

With the German ranks depleted by casualties and spread thin by fighting in France, and their reinforcement limited by an offensive on the Eastern Front, it was here, in this medieval town, that Belgian, British, French and Canadian and other Empire troops brought the German war machine to a grinding halt.

They were 35 kilometres from the North Sea coast, 85 from the French ports at Calais, and not gas, nor artillery, nor suicidal charges across no man’s land could bring the German army significantly closer to their objectives.

And, so, both sides dug in for what would amount to more than a three year stalemate, punctuated by constant rain, sucking deep mud, bone-shattering artillery barrages, more rain, more mud and brief periods of slaughter so vicious and massive that the farmers’ fields, country laneways, once-peaceful meadows and quaint villages were transformed into laboratories of death and destruction.

A row of Canadian graves, half of them unidentified, sits in the Passchendaele New British Cemetery outside the hilltop village where members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force consolidated a bloody but resoundingly empty victory at the Third Battle of Ypres late in 1917.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

“Battlefield looks bad,” Canadian General Arthur Currie wrote in a 1915 diary entry. “No salvaging has been done and very few of the dead buried.”

Temporary battlefield graves would be lost, and the number of unidentified corpses was unprecedented. In the Tyne Cot Cemetery at a former barn site outside Zonnebeke, 8,369 of the 11,968 graves belong to unknown soldiers.

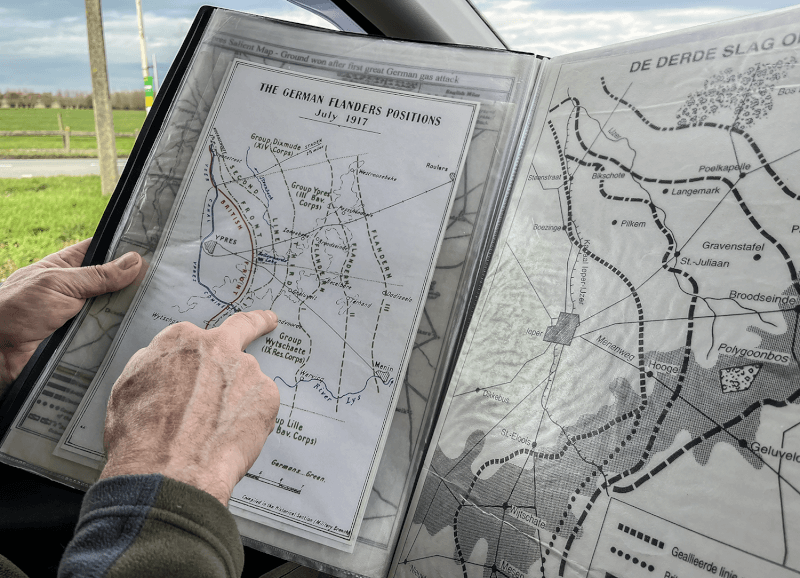

Guide Erwin Ureel charts the evolution of the fighting around Ypres. The lines show the movement of the salient during the course of the war.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

About one in seven Allied and one in 10 German soldiers succumbed to disease.

Recent research has found that a five-year, once-in-a-lifetime climate anomaly was responsible for the cold and precipitation that contributed to hundreds of thousands of battlefield deaths between 1914 and 1918 and the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1920.

Eight scientists from universities at Cambridge, Mass., Nottingham, England, and Orono, Maine, found evidence in core samples of glacial ice taken from the Swiss and Italian Alps. Traces of sea salt indicated the highest influx of cold marine air from the North Atlantic in a century during the years 1914-19.

Combining high‐resolution glacial chemical analysis with detailed monthly records of mortality from 13 European countries, the researchers found deaths peaked three times during the war—in the winters of 1915, 1916 and 1918—concurrent with, or immediately following, cooling temperatures and increasing precipitation.

The team of climatologists and archeologists cited studies showing how extreme weather shaped major battles such as Verdun (1916-1917), the Somme (1916), the Chemin‐des‐Dames (1917), and the Third Battle of Ypres, better known in Canada as the Battle of Passchendaele (1917).

The view of present-day Ieper from the site of the early Canadian line. The rebuilt Cloth Hall and St. Martin’s Cathedral can be seen on the right.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

The constantly wet and muddy conditions exacerbated problems such as trench foot and frostbite; in summer, they bore disease. Because the sucking mud of the European battlefields impeded the recovery and treatment of wounded soldiers, many drowned or died of exposure and pneumonia.

It was at it worst in Flanders and near Ypres itself, which is set in a low-lying, shallow basin just about 30 metres above sea level. To the east lies a series of low, wooded ridges.

“From these little hills came streams, more water, always water, but nothing to the amount that appeared as if by an evil force,” wrote Eileen Battersby for the Irish Times. “It was to rain every day but three in August of 1917.

“The land had once been reclaimed from the sea through careful draining and irrigation carried out for centuries. Battles had been fought there many times; a century earlier, Wellington and Blücher had bested Napoleon at Waterloo, only 65 miles away.”

A plaque on the wall of the Passchendaele town hall commemorates the nine Canadians who earned Victoria Crosses during the battle. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Survivors recalled struggling through the muck, their boots being sucked off their feet and sinking up to their waists.

To make matters worse, the topsoil around Ypres runs anywhere from less than a metre to three metres deep. Beneath it lies a non-porous clay—the foundation of the region’s brick-making industry, and a compounding factor in the formation of the lethal mud that became a signature element of the war.

Hundreds of millions of shells were fired over the course of the First World War, pummeling the soil into a thick pudding and, in Flanders, destroying the ditches and dikes that formed the area’s drainage systems. The mud made movement difficult, rendering no man’s land almost impassable and the transport of heavy guns nearly impossible.

Thousands of exhausted horses and mules perished attempting to haul gun carriages across the devastated, cratered and muddy landscape. It took six men to stretcher a wounded soldier through the morass.

Survivors recalled struggling through the muck, their boots being sucked off their feet and sinking up to their waists.

“It was mud, mud, everywhere: mud in the trenches, mud in front of the trenches, mud behind the trenches,” recalled Bombardier J.W. Palmer of the 26th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. “Every shell hole was a sea of filthy oozing mud.

“There were so many days when I don’t remember what happened because I was so damned tired. The fatigue in that damned mud was something terrible.”

“There was no ground to walk on,” wrote Major C.L. Fox of 502 Field Company, Royal Engineers. “The earth had been ploughed up by shells not once only, but over and over again, and so thoroughly that nothing solid remained to step on; there was just loose, disintegrated, far-flung earth, merging into slimy, treacherous mud and water round shell holes so interlaced that the circular form of only the largest and most recently made could be distinguished.”

Canadian Guide Steve Douglas trudges through the rain at Tyne Cot Cemetery, nine kilometres northeast of Ieper town centre. The cemetery is the final resting place of 11,961 Empire servicemen of the First World War, 8,373 of them unknown soldiers.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Added Fox: “Covered with mud, wet to the skin, bitterly cold, stiff and benumbed with exposure, cowed and deadened by the monotony of 48 hours in extreme danger and by the constant casualties among their mates, they hung on to existence by a thin thread of discipline rather than by any spark of life. Some of the feebler and more highly strung deliberately ended their lives.”

Palmer was severely wounded by shellfire during Passchendaele. “I was too damned tired even to fall down,” he said. “I stood there. Next I had a terrific pain in the back and the chest and I found myself face down in the mud.

“My pal came to me; he tried to lift me. I said to him, ‘Don’t touch me, leave me. I’ve had enough, just leave me.’ The next thing I found myself sinking down in the mud and I didn’t worry.” He was resigned to die before he found himself being carried away on a stretcher.

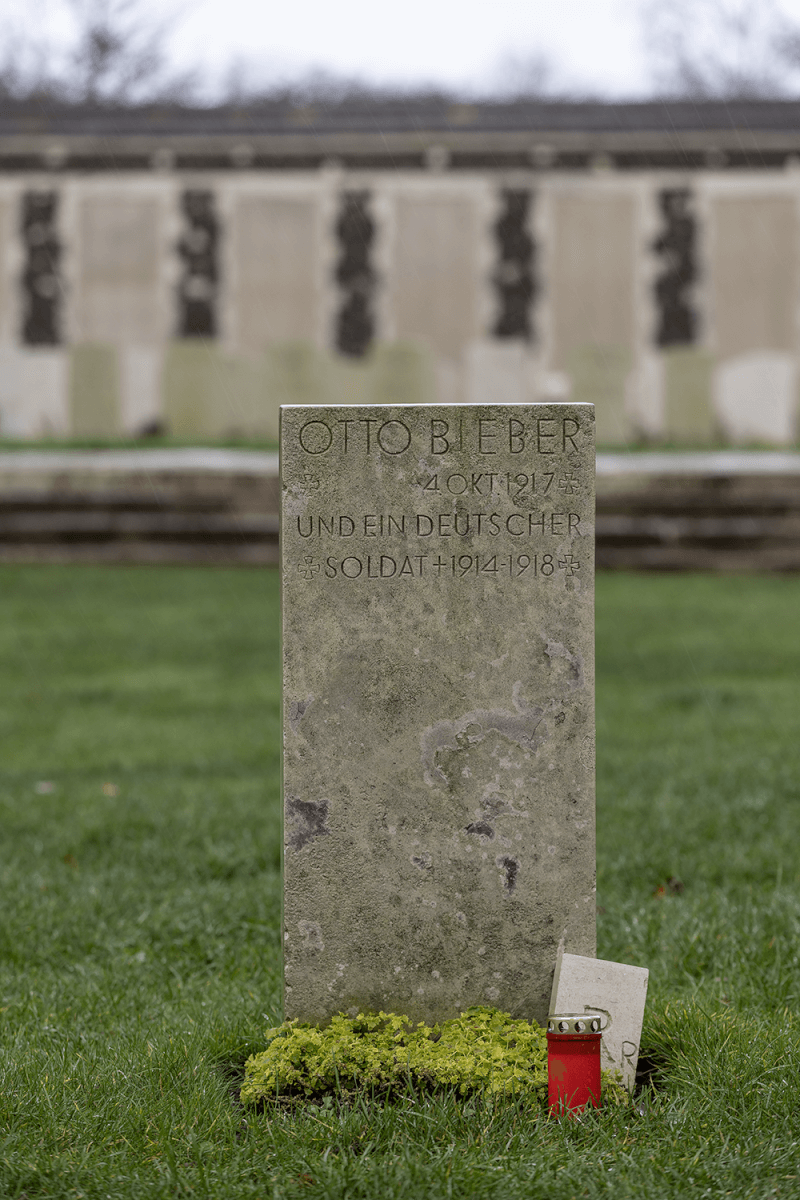

Among those buried in Tyne Cot Cemetery are four Germans.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Nary a building was left standing in either Ypres or the hilltop village of Passchendaele.

The fighting was brutal, the victories measured. Ground changed hands multiple times. The Second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915 marked the Canadians’ first major battle of the war.

Thousands of Canadians were killed or wounded in June 1916 during the 12-day Battle of Mount Sorrel, a strategic piece of high ground in the Ypres salient.

Nearly 16,000 Canadians were killed or wounded during the Battle of Passchendaele between July 31 and Nov. 10, 1917. It remains notorious for its heavy rains and shelling—and its futility: the victory, consolidated by Canadian troops, did nothing to help the Allied effort and became synonymous with the senseless slaughter of the First World War.

Senseless slaughter. And devastation.

Nary a building was left standing in either Ypres or the hilltop village of Passchendaele—or anywhere around them, for that matter. Towns and villages, evacuated for much of the war, were levelled. Many of their Flemish residents went to the Netherlands, some never to return.

The fighting had reduced Ypres’ great Cloth Hall to rubble, where traders from all over Europe had been bringing their fabrics and wares since the 17th century. Its next-door neighbour, St. Martin’s Cathedral, was a ruin, too.

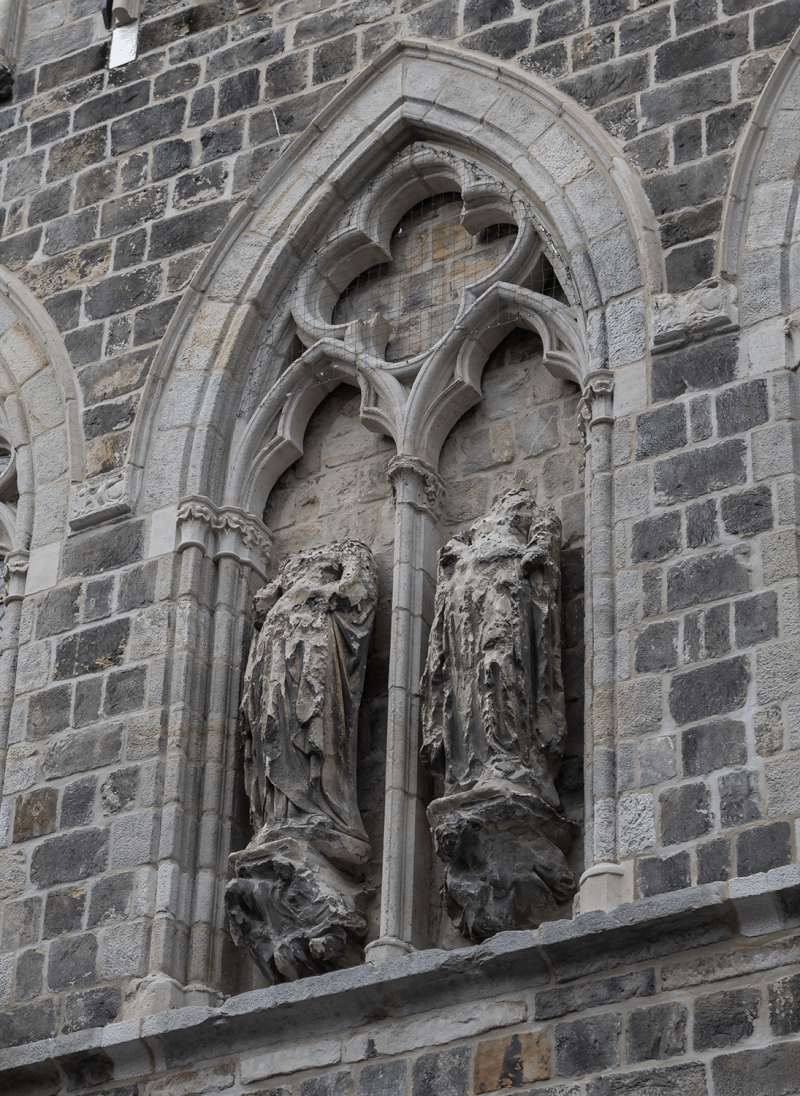

Some of the statues on the Cloth Hall were never repaired or replaced when the former trade centre was rebuilt after the war.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Today, Ieper is a thriving town of 30,000. The Cloth Hall and St. Martin’s were rebuilt after the war, largely from the original stone. Unrepaired statues damaged in the fighting still adorn the window frames, as they were at war’s end. The Cloth Hall is now the home of the impressive In Flanders Fields Museum.

A British helmet in the Salient Tours shop in Ypres shows evidence of the undoubtedly fatal wounds suffered by its wearer.

[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

This is the third of a series on the war in Flanders. Next, on Jan. 3, The Passchendaele Museum’s Names in the Landscape Project.

Advertisement