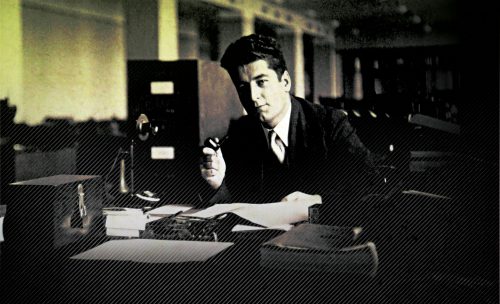

Gustave Bieler led a network of French Resistance members during the Second World War. [Jacqueline Bieler]

It was an inauspicious beginning—Bieler seriously injured his back when he landed on some rocks and he spent six weeks recovering in hospital under an assumed name. But he refused to return to England, and soon had set up one of the most successful spy rings in northern France, known as the Musician Network.

Bieler, who emigrated to Canada at the age of 20, spoke European French and was serving as a regimental intelligence officer when he was recruited by the Special Operations Executive, which established networks in occupied countries to foil Germany’s war efforts and gather intelligence.

The 25 teams in Bieler’s network were made up of French Resistance members who worked to derail trains, cut rail lines and blow up military targets. Once he and a couple of resistance members hid in a punt and drifted down a canal to place bombs below the waterline of a lock gate in a canal used to transport munitions. His teams destroyed German gasoline storage tanks, tractors used to tow barges and German equipment. Employed in the rail yards, they used axle grease larded with abrasives to cause train wheels to fall off.

In preparation for D-Day, weapons and ammunition were delivered by parachute.

In preparation for D-Day, weapons and ammunition were delivered by parachute and Bieler distributed them among his teams.

Belier operated in absolute secrecy, knowing there were collaborators and double-agents who would betray his network in a heartbeat if they could. He operated under the code name Guy in order to safeguard his wife and children in Canada.

His precautions paid off in mid-January 1944, when Bieler and his wireless operator Yolande Beekman were arrested. He maintained his silence, even under torture, giving the Germans not one name—not even his own.

Although the Germans were able to arrest about 50 members of one team, most of the Musician Network carried on their work right through D-Day, using weapons Bieler had supplied.

Even the Germans respected Bieler. He was not dispatched by gas or piano wire, as other Canadian spies were, but faced a firing squad in September 1944. The Germans even provided an honour guard.

Streets, buildings and memorials were dedicated in Bieler’s honour after the war in many towns and cities in northern France, and in Canada a lake, a veterans’ residence and a Quebec park have been named after him.

Bieler was, said fellow spy Gabriel Chartrand, “the great Canadian war hero.”

Advertisement