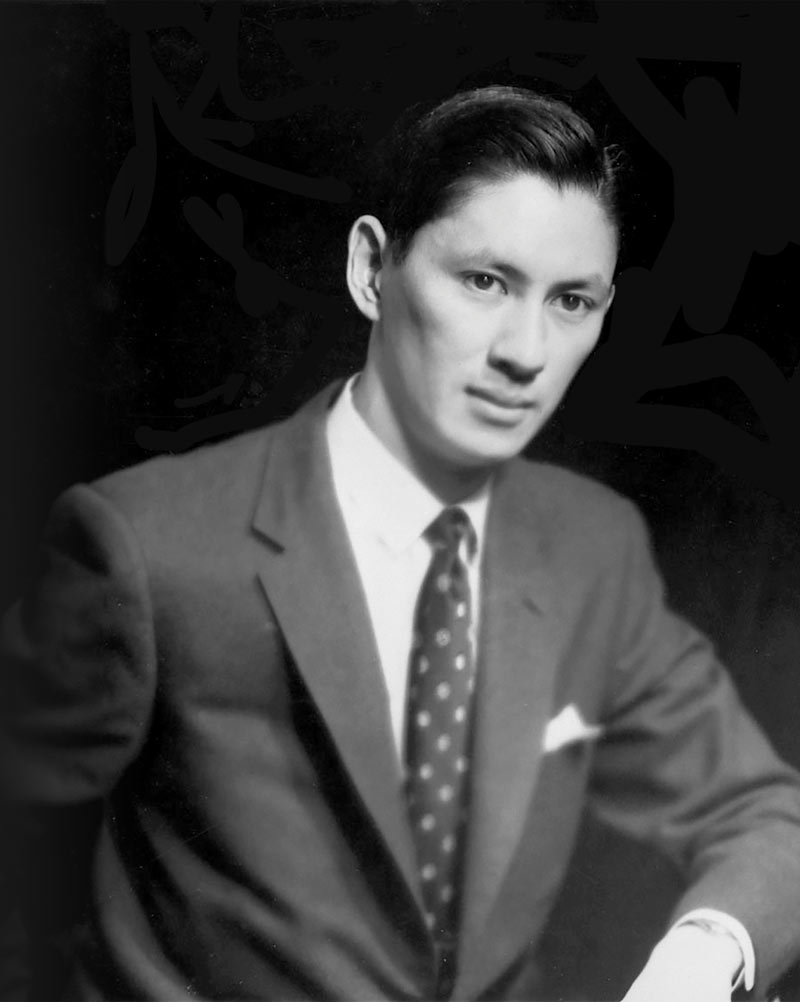

Douglas Jung circa 1958. [Arthur Roy/LAC/PA-047458]

When Douglas Jung was born in Victoria a century ago, no one could have dreamt he would one day become a veteran, a lawyer, a member of Parliament and a United Nations representative.

He spent his early life limited by laws that decreed where those of Chinese heritage could live and work and what jobs they could have. Racism was rooted deep in Canadian history.

Lacking labour to build the Canadian Pacific Railway in the West, workers were imported from China. Of the 9,000 western railway workers in 1882, 6,500 were of Chinese heritage. About 4,300 settled in Canada, mostly in B.C.

But once the line was completed, Chinese labour was no longer needed and Chinese immigrants no longer wanted by many Canadians. If Chinese “came in great numbers…they would send Chinese representatives to sit here, who would represent Chinese eccentricities, Chinese immorality, Asiatic principles altogether opposite to our wishes,” Prime Minister John A. Macdonald said in the House of Commons in 1885.

A younger Douglas (opposite, second from left), poses for a family portrait with older brothers Arthur and Ross.[The Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society]

That year, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act, imposing a $50 head tax; it was raised to $100 in 1901. Still, anti-Chinese racism grew; immigrants and residents of Chinese heritage were targets of bitter discrimination, hatred, riots and violence.

In 1903, the federal head tax was raised to $500. That amount proved an effective deterrent as only eight Chinese immigrants legally entered the country the following year. (Illegal entries were another matter.) Regardless, the tax ultimately wasn’t enough to stymie immigration. Before it was removed in 1923, some 82,000 Chinese migrants raised the money, sometimes with help from employers who needed more (or cheaper) workers.

Despite being born in Canada, Jung was not considered a citizen. His father, Jung Yik Ching, emigrated from China to Victoria, where he married Elizabeth Chan, a housemaid who became a teacher, in 1920. The Jung family couldn’t buy property in certain neighbourhoods or swim in public pools; they were not allowed in “white” restaurants and were segregated in movie theatres.

People of Chinese heritage were barred from becoming doctors, lawyers, pharmacists and from jobs in the public service. They mainly worked as labourers in sawmills and coal mines or in restaurants and laundries. They were not allowed to vote—regardless of whether they, or even their parents, had been born in Canada.

Jung was one of hundreds of young men who saw the Second World War as an opportunity to gain citizenship, over community objections to fighting for a country that treated them as second class.

“We were prepared to lay ourselves down for nothing. There was no guarantee the government was going to give us the full rights of Canadian citizenship.”

“Some of us realized that unless we volunteered to serve Canada during this hour of need, we would be in a very difficult position after the war ended to demand our rights as Canadian citizens because the Canadian government would say to us: ‘What did you do during the war when everybody else was out fighting for Canada?’” said Jung in a biographical video produced by Veterans Affairs Canada.

Jung joined the army, following his older brothers into military service. Arthur flew 30 sorties in Lancaster bombers, becoming a postwar commercial pilot. Ross, who served in North Africa as a surgeon in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, rose to the rank of major. After the war, he served with the U.S. Army Medical Corps and the Central Intelligence Agency before a long civilian medical career in Washington, D.C.

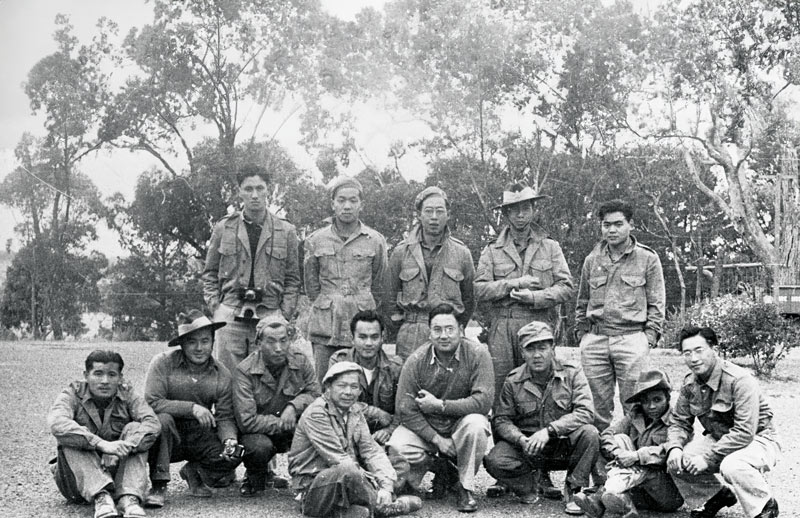

Jung sits for a photo while training in Australia in 1944. He was one of the first recruits for Force 136 (opposite, back row left), a Second World War Allied special ops team dedicated to the Pacific theatre.[The Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society]

When Japan entered the war in 1940, Chinese Canadians’ language skills were seen as an asset for spying behind Japanese lines in southeast Asia. Jung, who had taken an intelligence course, worked in Pacific Command Security Intelligence under Major-General George Pearkes.

The British wanted to set up an organization in Asia like the Special Operations Executive in Europe, which ran sabotage and espionage behind enemy lines.

“My group was probably the first to join up,” Jung said. Eventually 150 volunteered.

A British officer meeting with Pearkes asked Jung if he knew any other serving Chinese Canadians.

“I happen to know all of them,” Jung replied.

He and a dozen comrades signed a copy of the Official Secrets Act, agreeing not to talk about their wartime roles, and began Force 136 training about 15 kilometres north of Penticton, B.C., in a small cove they called Goose Bay, now the Commando Bay historic site.

Jung was one of the first recruits for Force 136, a Second World War Allied special ops team dedicated to the Pacific theatre.[The Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society]

Originally recruited for Operation Oblivion to build a resistance army in China, the mission changed to spying behind Japanese lines in New Guinea and Borneo—setting up intelligence networks, communication and observation posts and training local resistance fighters.

“And generally playing hell,” said Jung.

Force 136 members learned how to swim quietly, over long distances, burdened with a 23-kilogram pack and a waterproofed rifle. They mastered wireless equipment and the use of explosives. And how to kill silently.

They left in October 1944 for more exercises in Australia, where they took parachute training and learned survival skills to help them in a jungle filled with ferocious monkeys, venomous snakes, poisonous plants, leeches, mosquito-borne malaria, unfriendly locals and enemy Japanese.

“We looked like cutthroats,” said Jung in Unwanted Soldiers, a 1999 National Film Board documentary. “We were not in military uniform and we were unshaven, dishevelled. We were on our own and we had to survive.”

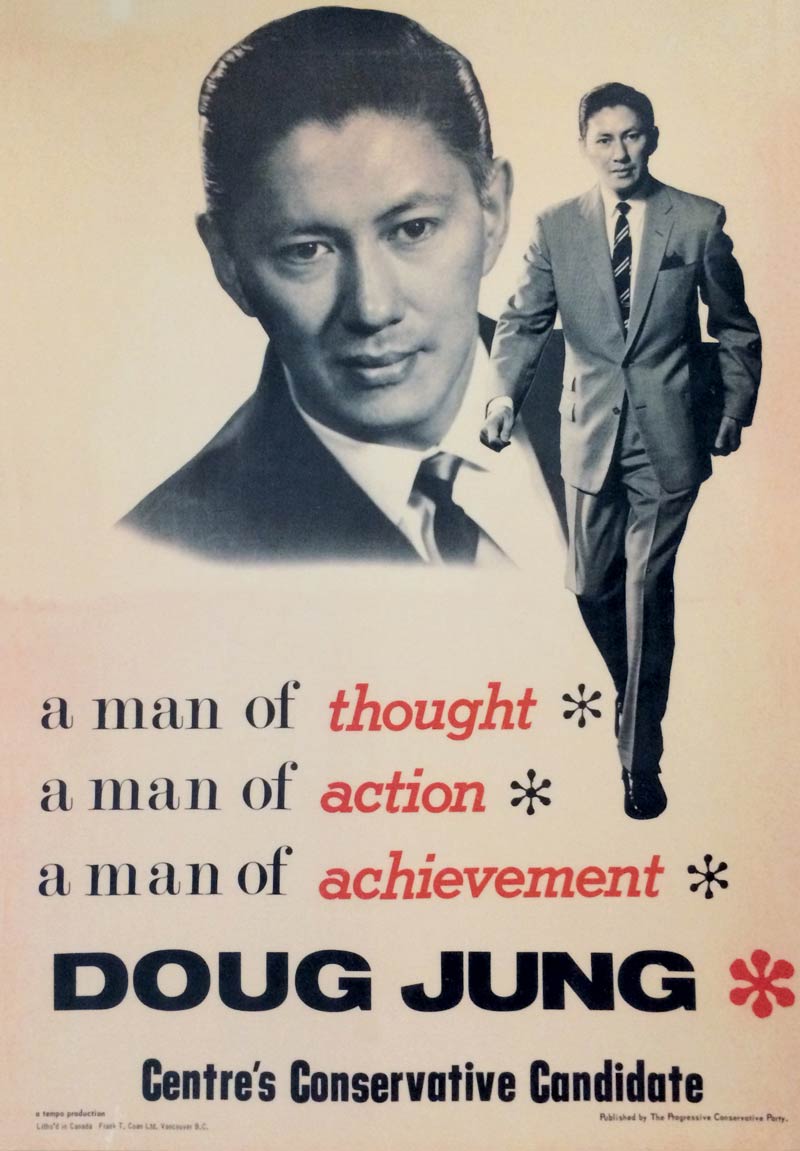

Jung was the first Chinese Canadian elected to Parliament in 1957 and served as the president of the Progressive Conservative Party youth wing. [Vancouver Public Library/Wikimedia]

They were issued cyanide pills; if captured, the Japanese would torture and kill them.

“We were prepared to lay ourselves down for nothing,” said Jung. “There was no guarantee the Canadian government was going to give us the full rights of Canadian citizenship. We were taking a gamble.”

Sergeant Jung broke his ankle during a parachute jump, ironically landing on an ambulance. The war ended while he recovered, but he remained overseas during postwar cleanup and rescue operations.

“Douglas Jung and others like him are directly responsible for making Canada the country it is today.”

“My father never talked about his war experiences,” said Jung’s son Arthur. Until, that is, one night he opened up while watching The Bridge Over the River Kwai, criticizing the film’s depiction of jungle warfare.

Jung returned to Canada in 1946. The country still didn’t recognize him as a citizen. His fight was not over.

“Learning how to live together is much more difficult than learning how to fight together,” he would later say in an address to the House of Commons.

“We were willing to work for everything that we wanted, which was no more than…the rights that every other Canadian enjoys,” said Jung in that VAC video.

“We never won any great military victories,” said Jung in Unwanted Soldiers. “But the victory that we did win far surpassed any military victory.”

It was hard work. Chinese veterans relentlessly campaigned for citizenship and challenged bans. Soon, they were swimming in community pools, getting public service jobs and studying for professional careers.

“We did something for the Chinese community no other group could ever have done,” Jung said at a veterans’ reunion in 1987. “Without our contribution to Canada as members of the armed forces during the Second World War, none of the rights that exist in the Chinese community today would be possible.”

Citizenship was finally granted in 1947, the year the Chinese Immigration Act was repealed. Chinese Canadians could finally vote in federal elections, and soon after, in municipal and provincial elections.

As a citizen and free to choose a profession, Jung first took a federal public service job, then studied law at the University of British Columbia; he began practising in 1954, specializing in immigration law.

Then he had several firsts for Chinese Canadians: appearing before the B.C. Court of Appeal in 1955; running in a provincial election in 1956 (he lost); and becoming national president of the Progressive Conservative Party youth wing.

In 1957, Jung became known as the giant killer after soundly defeating the favoured Liberal incumbent, Defence Minister Ralph Campney, in a federal byelection in the Vancouver-Centre riding.

“When you elected me to the House of Commons, I felt, for the first time in my life, that I was truly a Canadian,” he told a reporter the night of the election.

In 1907, Canadian roughnecks came “into Vancouver Chinatown where they smashed all the stores, took the Chinese and tied them together by their pigtails and threw them and their belongings into False Creek. Fifty years later that same constituency…made amends by electing the first Chinese Canadian member of Parliament,” said Jung in the documentary I Am the Canadian Delegate.

He was re-elected in the Progressive Conservative landslide in 1958 and served as a member of Parliament for five years. He advocated for equal standards for Chinese and European immigrants and for citizenship for Chinese forced to come to Canada under false names due to restrictive prewar immigration policies.

Families split apart by the head tax now faced restrictions on which family members could immigrate, including children over the age of 18.

“The people of Canada do not wish as a result of mass immigration, to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large-scale immigration from the Orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population,” Prime Minister Mackenzie King said in the House of Commons on May 1, 1947.

[The Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society]

Jung fought for amendments to immigration regulations to allow 6,000 wives and dependants of Chinese Canadians into the country and for financial aid for Hong Kong refugees.

“I believe we have a moral obligation to those early Chinese immigrants, who sacrificed so much and received so little, to become reunited with their families,” he told the House of Commons in 1960.

But immigration and equality for Chinese Canadians weren’t his only interests. Jung also fought for benefits for pensioners and students and urged the federal government to establish Canada as a leader in relations with Pacific Rim countries. He also helped create the National Productivity Council, the precursor to the Economic Council of Canada.

Jung was appointed to Canada’s legal delegation to the United Nations by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.

“By that one stroke he told the world that here in Canada we no longer had racial discrimination,” said Jung.

But the news travelled slowly.

“The first day I took my seat at the United Nations, one of the ushers came over to me and said, ‘I’m sorry sir, I think you are sitting in the wrong seat. This is for the Canadian delegate.’

“I said: ‘I am the Canadian delegate.’”

That was not his only impassioned feeling. “I don’t think that anyone can understand the surge of emotions that went through me when I took my seat…in that period of nine years from being a non-person, I had risen to the position of representing Canada at the United Nations.”

After leaving politics, Jung returned to his law practice and community service. He continued supporting veterans; was appointed a judge on the Immigration Appeal Board in Ottawa; served as director of Far East relations of the Former Parliamentarians Association; and was president of the Japan Karate Association of Canada.

Among Jung’s honours are the Order of Canada and the Order of British Columbia. He was also Life President of Unit #280 of the Army, Navy & Air Force Veterans in Canada.

In 1995, Jung suffered a heart attack while marching with fellow veterans; he died in 2002. After his death, a federal office building was named in his honour.

But he lives on.

“Douglas Jung was a trailblazer who was not only a pillar and hero to our community, but he and others like him are directly responsible for making Canada the country it is today,” wrote artist Miles Tsang in a 2020 Facebook posting accompanying a portrait of Jung he had created.

“His legacy should never be forgotten.”

Advertisement