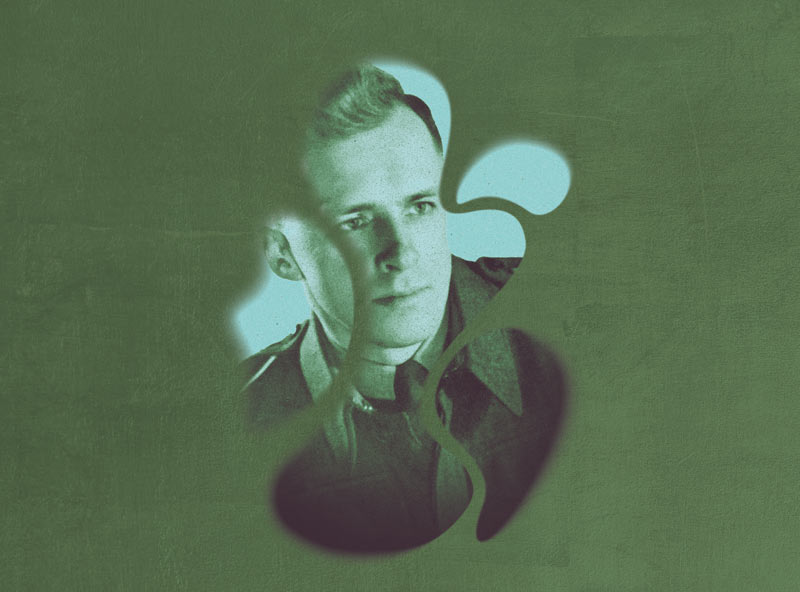

Lieutenant C. Hume Wilkins in 1943 [Courtesy Charles Wilkins]

When at the age of 11, I asked my dad if he thought he had killed any Nazis with artillery fire during the Second World War, he thought for a few seconds and said solemnly, “I hope so.”

It wasn’t the answer I or anyone else might have expected from the peace-loving son of a Quaker and, at that point in his life, a part-time preacher.

Not until years later would I come to appreciate that it wasn’t jingoism or a sense of theatrics that had prompted his response, but rather his refusal to shelter in any sort of personal revisionism. He had gone overseas to do a job and had done that job. And even with the sensibilities of an 11-year-old kid on the line, he was not about to invalidate his commitment by claiming he hadn’t meant any harm.

More than five decades after the end of the war, as my dad lay in his coffin in a little funeral parlour in Plattsville, Ont., a dozen or so WW II vets, each of them wearing his service medals and the beret of his regiment, gathered around their dead comrade, as they do in that community when an old soldier dies. They enacted a brief military farewell, and a young musician played “Taps,” then “Reveille,” and the men saluted, fell to ease and dispersed.

He led a reconnaissance troop in Italy, where he was photographed with two local children near Riccione in late 1944 [Courtesy Charles Wilkins]

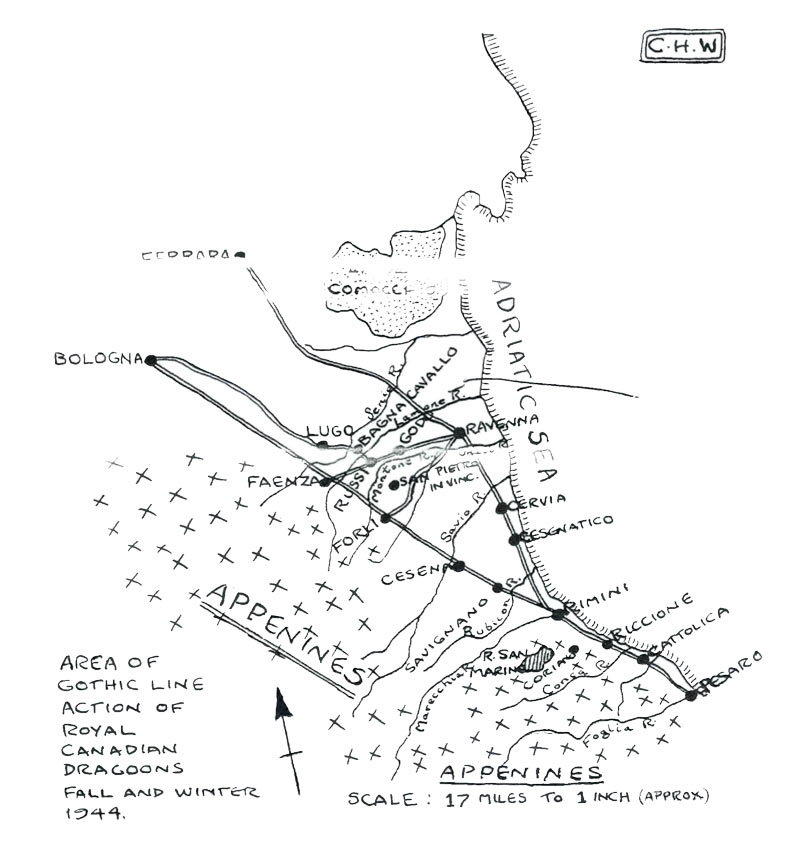

Around the time he drew this map (below) of the Gothic Line region.[C.H. Wilkins]

It was at that point that an amiable and soft-spoken air force veteran named Gow Harvey, who I did not know personally but who had known my dad for years, came over, shook my hand and asked in a suggestively conspiratorial whisper: “Do you know what your dad actually did during the war?”

It was like one of those Hollywood scenes in which the unsuspecting scion learns that the father or grandfather, the straight-up paterfamilias, was in reality a guy with a mysterious, perhaps shadowy, past. And for the briefest of moments, against all rational inclination, I felt frozen in the headlights—what on earth was he going to tell me?

Certainly, I didn’t know a lot about my dad’s years as a soldier. Life in the trenches simply wasn’t something he talked about. As an 11-year-old, I had gone with him once to Ottawa where he was speaking to a convention of bright high school matriculants and had been surprised to hear him tell them that for a year after the war, he had been adrift to the point where he had frequently considered suicide. He explained that as he walked the several-mile route back and forth to the University of Toronto as a student in 1946, he would sometimes stand for hours on the Bloor Viaduct, contemplating a jump.

But this was never mentioned again, not even in the car as we drove home to Cornwall, Ont., that night.

Until then, my impression of the war, or at least of my dad’s part in it, had been shaped by two bravura occurrences, both imparted to me by people other than my dad.

The first was that he had accepted a demotion in rank (captain to lieutenant) so that he could get overseas and fight. During a period when my mother felt my dad’s contribution was going unappreciated by other branches of the family, she made a point of speaking up about his voluntary relinquishment of rank and status, as if to show evidence of his selflessness and commitment to the cause.

The second thing was that he had been Mentioned in Dispatches, in other words cited for bravery in field reports to the high command in London. I knew this only because on a visit to my grandparents’ place in Hespeler, Ont., one summer, my grandfather showed me a letter, sent in 1945, advising that Lieutenant C.H. Wilkins had demonstrated “gallant and distinguished service in battle.” The letter (now in my possession) had been hand-signed in (what else?) royal blue ink by King George VI.

When Queen Elizabeth died recently, I was reminded that on a morning in 1952, as my dad shaved in the upstairs bathroom at 16 Parkdale Avenue in Deep River, Ont.—a bathroom in which he kept a little radio so that he could catch the early news from CHOV in Pembroke—my sister Annabel and I, who were still in bed, heard the bathroom door open and a restrained sob, then his plaintive voice: “King George is dead!” As the inspirational leader of the Allied forces, the king had mattered more to him than Churchill or the generals.

The cap badge of Wilkins’ Royal Canadian Dragoons; with his Aunt Grace at Clear Lake, Ont., in 1942; Wilkins’ medals; with family before his departure in April 1942; with brother Edgar, who served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, during leave in 1944. [Courtesy Charles Wilkins ]

My dad, I would learn years later, had fought in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany. However, at the heart of his war record were five largely unspeakable months in late 1944, during which he fought in the famously vicious Italian Campaign, a 22-month death match with the Germans that began in the summer of 1943, when thousands of Allied troops invaded the Italian island of Sicily.

By the time those men hit the mainland a couple of months later, two things had happened: Italian Fascists under leader Benito Mussolini who were spread all over Italy had surrendered en masse to the Allies; and some 300,000 German soldiers had poured into Italy from the north as replacements.

The Allied plan was to move north up the Italian boot—basically 600,000 Allied soldiers (as many as 300,000 of whom might be active at any one time) pushing 300,000 Nazis back toward Germany. And here I must pause to note that during this year of 2023 we are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the start of that heroic initiative.

In all, nearly 100,000 Canadians fought in the campaign and more than 5,000 of them lost their lives. They were constantly being replaced or relieved by other soldiers, and when my dad arrived in Italy, some six months after the initial landing on Sicily, he came as reinforcement for the 1st Regiment of The Royal Canadian Dragoons. He had recently completed two months of tank training in Algeria—“blowing up the desert,” as he once characterized the activity.

But he was not a “tank man”—he was in reconnaissance, “recce” as they called it. In that capacity, he led a troop of 15 gunners and drivers—risk-taking swashbucklers trained to prowl the front lines looking for enemy weaknesses, which they did either on foot or on their knees or bellies in the Italian mountains, or when it was possible, in fast armoured cars: either big American Staghounds or “Stags” (14-tonne vehicles, each mounted with a 37mm gun), or smaller Daimler Scouts, “Dingos,” equipped with a Browning machine gun.

By mid-1944 Rome had been liberated from the Nazis and fierce battles, such as the one at Ortona, had been won, bringing both respect and great losses to the Canadian troops, more than 500 of whom died in taking the mountain city from the Germans.

Meanwhile, the focus of the campaign had shifted to what Hitler had named the Gothic Line, an east-west continuum of easily defendable and fiercely defended trenches and gun placements in the area of the Foglia and Marano rivers, near the Adriatic resort cities of Riccione and Rimini, and moving inland into the mountains north of Florence.

The line was really less a “line” than a kind of buffer zone some 15 kilometres wide. Its thousands of concrete gun nests, bunkers and trenches had been built hastily with slave labour and, in effect, represented Hitler’s last stand in Italy. And it would be the job of my dad and the thousands who fought with him to somehow penetrate this last wall of defences, so that the British Eighth Army and the U.S. Fifth Army could get in behind the Nazis and finish them off.

An Otter Light Reconnaissance Car, similar to the vehicles Wilkins used in Italy. [Terry F. Rowe/LAC/PA-201359]

But on the day I met Gow Harvey at my dad’s funeral, I didn’t know any of this. Through the first 50 years of my existence, my dad had told me exactly one war story, had explained to me one day when I was about 12 how a communications wire he and his men had laid down had been broken by exploding shells. He was attempting to impart a moral principle, and the gist of things was that if he sent one of his men to mend the wire, he would never have been able to live with himself if the man had been killed or seriously injured. So, he went himself, belly-wriggled out across a field into no man’s land, in the dark, as machine-gun fire rattled around him. The moral of the story, as he articulated it, was that you never asked somebody to do a job, particularly a tough one, that you wouldn’t do yourself.

“Do you know what your dad actually did during the war?”

I recall another time when I was perhaps eight, and my dad’s gunner, a trooper-turned-lawyer named Jim Braden, told me jokingly about a vague time in a vague place where and when my dad had brought several live chickens into the turret of their Stag, so they would have them handy for dinner. When another of the vehicle’s gunners released a volley of machine-gun fire, the chickens leapt up in tandem and dropped dead of shock on the floor. So, the men didn’t have to kill them later.

Meanwhile, back at the funeral parlour, if Gow had something to tell me, I guessed it was time to hear it. “What your dad and his men did,” he said now, “was the most dangerous, the most stressful, the most deadly work any soldier ever had to undertake.”

Gow was not easily impressed; he had been a gunner on a Halifax Mk II bomber and, as the only survivor of a flaming crash over Leipzig, Germany, in early 1944, had been taken prisoner and had spent some extremely difficult months, at a fraction of his normal weight, in Stalag Luft 6, a famously brutal Nazi prisoner-of-war camp in what was then East Prussia.

Gow reported that he had gone to visit my dad one day in about 1995. My dad would have been 83. They had talked for three hours about the war in general, about the Allied command, Churchill, Montgomery, the U.S. forces, Patton, North Africa, Rommel, bully beef, the Fascists, the deaths of Mussolini and Hitler, the Nazis, or “Nazzys” as my dad always called them, until eventually Gow said to him, “Now, Hume, you’ve told me all about everything except yourself. You didn’t get Mentioned in Dispatches by hiding in a trench.”

Fighting at the Gothic Line.[DND/LAC/4233144]

Life on the front lines was an emotionally messy, non-stop struggle to stay sane.

And with that, my dad had told him how it was, describing, as Gow recalled, how night after night, his little troop of armoured cars, sometimes just one of them, part of ‘C’ Squadron, would patrol the Nazi positions along the Gothic Line, picking up information, firing the odd shell to see who responded, looking for weaknesses—and how at times, when a car was too obvious or cumbersome, they would leave it several hundred metres to the rear and would go on foot, or on their bellies, sometimes along dried up river or creek beds, attempting if possible to get in among the Nazi encampments and gun placements, or, on rare occasions, even behind the front-most trenches and gun nests, gathering information, sending back radio reports as they were able.

The idea was to tell headquarters how many Jerries were out there, how well they were armed, whether there were reinforcements, supplies, food, proper trenches—did they have tanks, and if so, how many? My dad told Gow how at times, in the middle of the night, he and his gunner, or he alone, would be close enough to Nazi trenches or lookouts that they could hear the Jerries talking, or laughing as they played cards or made tea in the darkness.

“If these reconnaissance guys got caught,” said Gow, “it wasn’t about being taken prisoner.” As far as the German infantry were concerned, anybody crawling around under their noses represented a lethal threat not just to the security of a few troops or trenches, but to the whole Gothic Line and, hence, the outcome of the war. Beyond which, Gow concluded, the snooping was an insult to the Jerries’ strategic intelligence.

Perhaps understandably (and undoubtedly in violation of the Geneva Conventions) the Nazis discouraged such activity by summarily executing personnel such as my dad if they managed to catch them. In one notable incident, according to Gow, the Germans left a couple of corpses draped over fences—a resonant warning to anyone who might follow.

“Can you imagine,” Gow said, “what this kind of work did to a soldier’s head night after night, week after week, on the front lines?”

As we talked, I glanced several times at the shrunken figure lying in the box, his war medals and decorations laid out on top (including his favourite, the little bronze oak leaf awarded to military personnel Mentioned in Dispatches). One of the things that gives me pride in my dad’s war record is that he was not a warrior at heart, not an athlete nor even particularly a competitor, but rather a poetry-loving, Shakespeare-quoting intellectual, a guy who by the age of 17, in 1929, had read every novel in the Hespeler library, had survived spinal meningitis (which he told me once had permanently diminished his co-ordination) and who later in life taught literature and philosophy, loved opera broadcasts on CBC Radio and read a hundred books a year.

And had, of course, fought like a wolverine in Italy.

Gow and I promised to get together, but we never did, and for the next 20 years, my awareness of my dad’s war contribution stayed pretty much as it was that day in the funeral parlour. Around 2010, I came across a sheaf of my dad’s wartime letters to my mom and other family members. But many of the details had been edited out, presumably for security. On Remembrance Day, I would shiver at the cenotaph and think about the things Gow had told me. But despite everything, any sense of my dad’s war remained a sketch.

Then a kind of miracle happened.

Out of the blue in early 2022, a Dutch historian named Edwin Meinsma emailed me explaining that he was writing a book about the Canadian army’s role in the liberation of his province of Friesland in the northern Netherlands in 1945. The name of a Canadian lieutenant, C.H. Wilkins, had come up repeatedly in his research—was this person by any chance my father, or a relative? If so, could I tell him more?

The astounding thing was that along with the request came a lightly redacted electronic copy of a 140-page diary in which my dad had documented the roughly nine months from his first action in Italy to his final deployment in Germany, where on May 8, 1945, word came down that the nightmare was over, the Germans had surrendered and Hitler had committed suicide.

Meinsma had acquired the diary, I believe through an archival service of some sort, or perhaps the Canadian War Museum, and my immediate question was why my dad had never shown it to me—or even mentioned it. I wondered perhaps if the particulars of its contents were in some way uncomfortable for him. Later, it seemed more plausible that he simply didn’t want to think about those contents anymore, or the experiences that had spawned them. The year of suicide fantasies when he had come home, and the inner chaos represented by those fantasies, were pretty good evidence that he no longer wanted to think about the war.

Regardless of what the diary meant to him, it was a gold mine for me—a rich, personal, invariably illuminating account of the role he and his comrades played in the struggle to break through the Gothic Line and end the Nazis’ dominance of northern Italy. More significantly, it offered a great skein of detail that for me had always been missing.

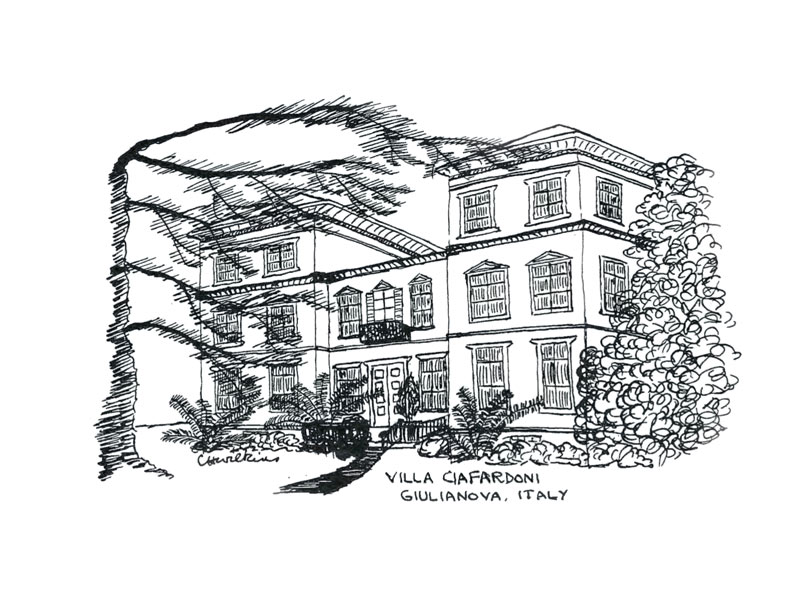

Wilkins’ sketch of the villa in Giulianova where he and his squadron took leave in 1945. [C.H. Wilkins ]

Everything was there—from what the fighting men feared (good marksmen, confusing orders, inadequate maps) to how they fought (relentlessly), to the fine points of their daily diet: the despised bully beef, the hated hardtack, the mystery soup; the chickens and piglets and calves “liberated” from roadside farms; the occasional small treat (a 1944 Christmas parcel from the British YMCA contained an orange and a package of Life Savers for each man). Unfortunately for the troops, they were often unable to harvest the local grapes and apples, because the retreating Nazis had booby-trapped the vines or tree branches, or placed land mines, including the infamous Bouncing Bettys, in the vineyards or orchards.

What is not commonly perceived, but is made clear by the diary, is the degree to which life on the front lines was carried on among the civilians who called the territory home. In some cases, they were embittered Fascists, Mussolini loyalists who spurned or even spat at the advancing Allies. More often, they were folks who had lost everything except their will to help the Allied infantry and artillery in the slow grind north: 90-year-old women, toothless old men, farmers, teachers, nurses, people quietly overjoyed to see the last of the Nazis and the arrival of the Allied army.

The lot of them, civilians and soldiers, lived knotted up together in the wreckage of what was: houses with no doors, orphanages with no roofs, monasteries and villas with five-metre holes blown in the walls. Headquarters was anywhere it could be established, preferably in a place with at least a smattering of comforts—say, a stove, a few chairs, a mattress or two and, perhaps above all, a windowless subterranean room, where at night the men could light a simple, single candle so they could peruse maps, read books or read one another’s faces without fear of giving away their position.

If no accommodations were available, the troops did the obvious and slept in trenches or foxholes, sometimes in the mud—or, if it was my dad’s troop, slept curled up in the turrets of their armoured cars.

Amid all of this, the diary makes clear, life on the front lines was an emotionally messy, non-stop struggle to stay sane: was the young soldier who, at the first sound of a machine gun, leapt out of the trenches and ran screaming toward the enemy gun nests; was another man’s night sweats (in the cold); another’s shivering fits in the warmth of the armoured car; was the crazy-making eeriness of the night watch—something moving out there in the shadows and, with it, the temptation to fire off a few rounds, or shine a light, except that in so doing you’d betray your position and would immediately take a shelling from across the lines.

“If you weren’t on watch,” said my dad at one point, “you were on wait.” Waiting until dark; waiting for a signal; waiting for orders; waiting for dawn; waiting out a barrage of machine-gun fire. Waiting for desperately needed reinforcements, or until just the right moment to come roaring up out of the riverbed and onto the German trenches.

At other times, soldiers waited patiently for Red Cross vehicles to go out into no man’s land and fetch a dead comrade and bring him in for burial; or fetch a “quiet” Nazi —which is to say a dead one—for delivery back north across the lines. A favourite deceit of the retreating army was to booby-trap the corpse of a fallen comrade, on the chance that someone from an advancing unit would tire of seeing or smelling it and would come out to bury it and would himself be blown to death.

The diary was a rich, illuminating account of the role he and his comrades played in the struggle to end the Nazis’ dominance of northern Italy.

Unidentified Canadian soldiers in Italy in December 1943[F.G. Whitcombe/DND/LAC/PA-204299]

“Battle is a raid on the senses,” notes the diary: the smell of cordite; the whine of an incoming shell or a “moaning Minnie;” the howl of an approaching bomber; the muffled thud inside the Staghound when a shell is fired. It has been said that the most terrifying sound of war was the click underfoot when an infantry soldier stepped on a Bouncing Betty and was unable to move without detonating the device and losing his legs.

On a night in October 1944, just north of Riccione, my dad, on reconnaissance, recorded his desperate attempts in the dark to orient himself between the “staccato trill” of the German MG42s and the clattering “rain-on-the-roof” of the Canadians’ Vickers machine guns.

He was a subtle writer, so it does not surprise me that the diary’s most understated lines are in his attempts to convey the devastation the troops felt over the loss of a comrade—the report from the front, the torn corpse, the shallow grave and brief committal, the wooden cross inscribed and installed:

“Two days later we stood by the graves of the dead, and gazed at the inscriptions lettered on the crosses over their heads, (K/A, Killed in Action). Padre Cleaverdon read the brief service. It comforted us to know that our friends were lying decently in the dark earth, safe and sheltered, after two long days on the battlefield when we could not reach their bodies because of the enemy snipers who hung about waiting to shoot anyone who exposed himself.”

It was not just the Allied dead who commanded my dad’s attention:

“Late in the afternoon we harboured in a grassy vineyard, where the ripe grapes hung in to easy reach. A pale young German lay at the road junction, his fighting days done. I never quite lost the morbid interest I had then in seeing their quiet bodies. A live German, too, had a little of the fascination of a wild animal; it is not easy to think of your dreadful hidden enemy as a man like yourself. I suppose the Germans had the same idea of us.”

As for living Nazis, when ‘C’ squadron moved into a villa that had recently been inhabited by the Germans, my dad was surprised and, I think, moved, to find the novel Resurrection by Leo Tolstoy left behind by an enemy officer—this at a time when my dad himself was reading Tolstoy’s War and Peace; brothers in literature if not in arms.

At other times, there was no such familiarity: “There, in the little town,” he writes in January ’45, “we saw for the first time German prisoners-of-war working under guard; and the old weird feeling of mystery came over us; everyone watched them, fascinated, as if they were men from the moon.”

Given my dad’s temperament, I am not surprised that the diary contains little sense of his personal influence on the advances and small victories he describes, or of his once-vaunted bravery under fire. In reference to the fear he sometimes felt, he recalled a sunrise reconnaissance mission along the banks of the Lamone River in December 1944:

“I crept forward to inspect the pits the Jerries had dug into the bank, and as I turned away another shower of shells came down. All I could do was throw myself down

in a shallow ditch, about as deep as a washbasin, and bury my nose. A piece of shrapnel knocked my helmet off, but I didn’t dare reach for it unless I wanted to lose my arm. For me, looking back, it was one of perhaps a dozen truly bad moments of the war; I couldn’t see how I’d get out alive. But eventually, like the other moments, it passed, and I had a sense of a guardian angel somehow looking out for my wellbeing.”

My dad had an equally pointed sense of the reassurances of a decent shave, a cup of tea, a shot of rum, a word or two of encouragement from the major as his little troop came in off another night of snooping, of whispering, of rumours and camaraderie.

German prisoners are escorted by men of the 1st Canadian Division around the same time.[Terry F. Rowe/DND/LAC/PA-167915]

Thus it was that the Italian Campaign pushed north: one riverbed, one canal, one creek bed at a time—the Salto, the Foglia, the Rubicon, each depleted waterway transformed by the Nazis into an all but impenetrable barrier of gun nests and hideouts and landmines, the lot of it backed by tanks and artillery, and if these failed, by thousands of square kilometres of impassable mountains to the northwest.

When at last, during the late winter of 1945, I Canadian Corps broke through the Gothic Line for good, The Royal Canadian Dragoons, including my dad’s squadron, had been taken off the front lines for a rest, first in the little town of St. Pietro, then in Giulianova overlooking the Adriatic.

It was from there, after weeks of rumours and speculation, that they were redeployed to Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. Near the Dutch town of Leeuwarden on the evening of May 5, 1945, they received word that a ceasefire had been ordered and the war was about to end.

“After so long on the lines,” my dad wrote in his diary that night, “it is hard to know what to do or think having been commanded to refrain from war. Being realists more than philosophers, the men, it seemed, paid minimal attention; a soldier takes everything in stride.

“For some of us there were tears, and that night in darkness I found myself thinking back over the months that had passed…England…North Africa…the hard days under fire in Italy…the outings into the night to discover what needed to be discovered.”

There was evidence in the writing that my dad was already feeling a weight over all that had passed, and by his memories of the campaign. But he said he felt, too, that the troops had:

“done what we came to do—had left the enemy a little weaker, undoubtedly a little closer to surrender.

“It may seem presumptuous, but I think we represented our country and supported our allies as well as possible. And we supported one another.

“Our war is over,” he said in conclusion. “Whatever remains to be done here will be carried out on time borrowed from home—which once again,

happily, is a real possibility, and no longer just a dream.”

Advertisement