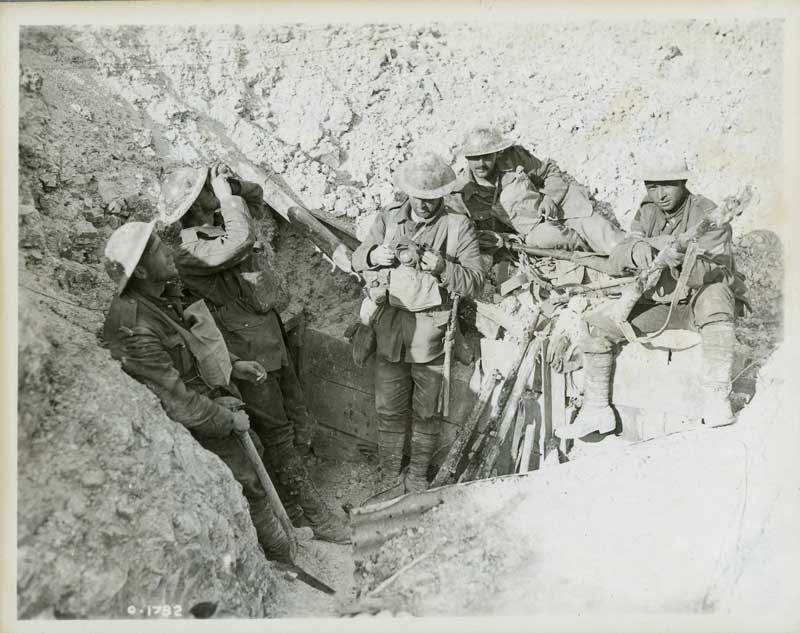

Soldiers take some sustenance near German lines at Hill 70 in August 1917.

[LAC/PA001596]

For a young man with Canada in his sights, he couldn’t have found a spot much farther away, or much different, from his home, settling as he did in McBride, B.C., a Rocky Mountain village that in 2021 numbered just 588 people.

It was 1913, a fortuitous time for a carpenter like Atherton in a place like McBride.

Far from the Roman road that ran through his hometown where urbanization and industrialization took root in the 19th century, McBride was a new settlement located on Mile 90 of the brand-new Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

A train station was being built on what would become Main Street. The area was growing on the strength of agriculture, logging and the railroad.

Atherton, however, would never see much development past the train station. A year after he arrived, a world war broke out in Europe, a war from which Atherton would never return.

Advancing under the cover of a creeping barrage, the Canadians fired and faced millions of machine-gun rounds.

In March 1916, the then 23-year-old tradesman hopped the eastbound train for Edmonton, where he enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

The identification disc found with Atherton’s remains was indecipherable before the Canadian Conservation Institute got ahold of it. They found enough there to link it to the private killed on Aug. 15, 1917, at Hill 70.

[ GoC]

He was soon in the thick of the fighting on the Western Front. By August, he was headed for one of the bloodiest battles of the war, the Somme. On Sept. 26, 1916, he was shot through the left thigh during the brutal fight for the German fortifications at Thiepval, one of the 10th Battalion’s 241 casualties.

As many did in the mud and filth of 1917 France, his wound turned septic. Atherton would be hospitalized for 72 days before he was allowed to return to duty in March 1917. It appears he missed the fighting at Vimy Ridge in April, but he was back with the 10th by mid-May and fought at Hill 70 in August.

It was there, on the outskirts of the French coal-mining town of Lens, that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps under General Arthur Currie met four divisions of the German 6th Army. The hill was just 10 kilometres from the ridge at Vimy where the Canadians had earned what would be their most famous victory.The gradual, chalky, barren slope that formed Hill 70 was about half Vimy’s height and less than half its length, yet it took 10 days to wrest it from German hands—more than double what it took to win the long sought-after Vimy.

Hill 70 had been under German control since 1914. The defenders were tenacious, dug-in and well concealed. The Canadians were expected to inflict, and incur, major casualties as they aimed to draw German troops away from the 3rd Battle of Ypres, and make the German hold on the French town untenable.

Canadian and British guns fired almost 800,000 shells in the days before the attack, killing, wounding and wearing down the German defenders as shrapnel cut barbed wire, disabled artillery emplacements, hampered communications and collapsed trenches.

Advancing under the cover of a creeping barrage, the Canadians fired and faced millions of machine-gun rounds. Royal Engineers launched a smokescreen just as the attackers began to move.

As part of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade, the 10th Battalion was among the Canadian units that reached the Blue Line, 550 metres out, in 20 minutes. It pressed on to the Green Line, which it reached early the next morning.

The fighting would eventually come down to close-quarters, hand-to-hand, life-or-death desperation. Six Canadians were awarded Victoria Crosses for individual actions at Hill 70, and all but two involved bloody close-quarters fighting.

More than 10,000 Canadians were killed, wounded or declared missing in action at Hill 70. The 1,300-plus MIAs were among the highest of any Canadian battle of the war.

Atherton was reported wounded on the battle’s first day. Soon after, word spread that he was dead. He was 24 years old.

His sole beneficiary was his mother, Sarah Ball, who was still living back in Leigh, England, where he’d been born. On Nov. 14, 1919—more than two years after her son’s death—she received a letter from the officer in charge of wills with a copy of Atherton’s last will and testament.

Canadian soldiers in a captured German trench during the Battle of Hill 70 in August 1917. The soldiers on the left scan the sky for aircraft, while the soldier in the centre appears to be re-packing his gas respirator into the carrying pouch on his chest. Dust cakes their clothes, helmets and weapons.

[DND/LAC/3395589]

“I have not yet received a report from our London office as to any personal effects that may have been recovered, nor is the Pay Account expected to be received here for some considerable time yet,” wrote a Lieutenant Walker.

What happened to the 24-year-old private and how he disappeared may never be known.

“To be honest, I don’t look for that,” said Dr. Sarah Lockyer, the forensic anthropologist who analyzed Atherton’s remains and wrote the investigation report. She is the casualty identification co-ordinator for the military’s casualty identification program.

“The remains are stored typically in a location close to where they were discovered,” she said, explaining that she has seven to 14 days to analyze them and the focus is identification, not cause of death.

“So, it’s things that come from the biological profile—age estimation, height estimation, if there is something weird about the teeth or is there like a healed fracture that maybe is in the personnel files and things like that.

“At the end of the day, they were killed in action, so they all died of war.”

Furthermore, people killed in action were often buried in hastily dug graves close to the front, sometimes with only a rifle or wooden cross to mark their location. A proper headstone would be provided later on or the remains would be unearthed and transferred to formal cemeteries.

These plots were often damaged by shellfire. In 1918, many were overrun, first by advancing enemy and later by the Allies pushing eastward again. Over time, the locations of many registered and otherwise documented graves were obliterated.

Brass Canada shoulder title found with the remains of Private Atherton.[GoC]

“There’s a lot of construction going on in that area and the remains are just kind of popping up everywhere,” said the Moncton, N.B., native.

Atherton’s 10th Battalion suffered 429 casualties at Hill 70, 73 of them with no known grave. Battalion dead included one of the six Canadian VCs—Private Harry Brown, who was caught in a counterattack the day after Atherton was killed.

Communications had been cut; Brown and another soldier were dispatched with identical messages. The other messenger was killed.

“Private Brown had his arm shattered but continued on through an intense barrage until he arrived at the close support lines and found an officer,” said his citation. “He was so spent that he fell down the dugout steps, but retained consciousness long enough to hand over his message, saying ‘Important message.’”

Brown then lost consciousness and died in the dressing station a few hours later. He was just 19. “His successful delivery of the message undoubtedly saved the loss of the position for the time and prevented many casualties.”

Lockyer said Atherton’s relatives were difficult to track down. He had only one sister, who the anthropologist wasn’t sure had any children.

On July 11, 2017, combat engineers clearing century-old munitions found human remains near rue Léon Droux in Vendin-le-Vieil, north of Lens. Commonwealth War Graves Commission staff recovered them and several artifacts, including an identification disc and 10th Battalion insignias—a cap badge with the battalion’s distinctive beaver-and-crown emblem among them.

In time, the Canadian Forces Forensic Odontology Response Team, along with the Canadian Museum of History and the Casualty Identification Review Board, went to work, applying historical, genealogical, anthropological, archeological and DNA analysis to the job.

Canadian C10 numbered collar badge found with the remains of Private Atherton. [GoC]

Lockyer said Atherton’s relatives were difficult to track down. He had only one sister, who the anthropologist wasn’t sure had any children.

The DNA donor and the next-of-kin were, in fact, two different people, she said.

“They’re both first cousins, four times removed—or something like that. They’re quite far away from Atherton. It happens with his family tree.”

Despite the hurdles, the investigators had confirmed by October 2021 that the remains, indeed, belong to Atherton. They are to be buried in the Loos British Cemetery in Loos-en-Gohelle, France. No date has been set.

The Canadian Corps only partially accomplished its goals at Hill 70. The Canadians prevented the Germans from transferring local divisions to the Ypres Salient, but failed to draw in troops from elsewhere. They were later unable to take Lens itself.

Both sides concluded in their assessments of the battle, however, that they succeeded in their attrition objectives. Hill 70 was costly for all, in no small measure due to extensive use of poison gas.

As is the practice for found soldiers, Atherton’s name will remain with 11,284 others on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, commemorating Canadians of the First World War who were killed on French soil and have no known graves.

Advertisement