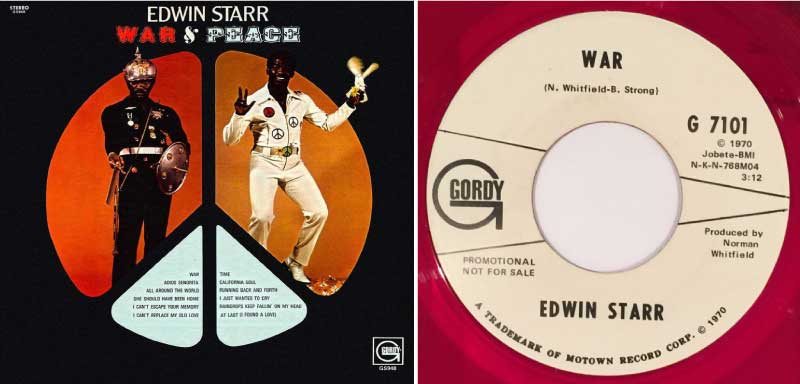

Edwin Starr’s 1970 album War and Peace featured the No. 1 single “War,” which asked the question: “What is it good for?” The Temptations first released the song three months earlier, but it was Starr’s version that earned the plaudits.

[Motown Records]

His answer, sung in defiance of those who would challenge him: “Absolutely nothing.”

Indeed, author John Steinbeck once said that “all war is a symptom of man’s failure as a thinking animal.” More recently, American photojournalist Aaron Huey, who’d seen his share of conflict, described war as “the greatest failure of mankind.”

Why, then, is there the constant need to invoke “war” whenever people seek to motivate others on a particular issue?

There’s the war on drugs, which evidence suggests was something else altogether; the war on crime, which has tended to perpetuate the problem more than solve it; the war on poverty, which no government has effectively addressed; the war on Christmas, which never existed; and endless wars on disease—from cancer to COVID-19.

Like real wars, these “wars” are often a last resort that addresses the symptoms of a problem, not the cause, and thus are doomed to fail.

Richard Nixon gives his trademark “victory” sign during July 1968 campaigning for the presidency in Paoli, Pa.

[Ollie Atkins/White House/WIkimedia]

The Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, founder of Taoism, has been credited with first uttering the idiom: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

“Wars” on social issues are like that. They rarely succeed in solving problems, and sometimes serve to perpetuate them. It is easier, after all, to rely on shelters and soup kitchens, even to build low-cost housing, than to address the fundamental causes of poverty—lack of education, lack of jobs, technological change.

Likewise, it’s easier to impose mandatory sentencing, contract private prisons and fill them with drug addicts and petty criminals than to address the underlying poverty and mental-health issues and develop effective prevention, rehabilitation and recovery programs.

Declaring “war” on anything is a dramatic act designed to shock, motivate and sometimes manipulate people on an issue. Some would argue it’s an admission of failure.

When United States President Richard Nixon declared the war on drugs, rallying Americans around a supposed crisis on American streets and neighbourhoods, the result wasn’t a battle with a drug epidemic.

Nixon’s so-called “drug war” started out largely as a public-health crusade.

Nixon and subsequent administrations championed the cause in order to criminalize Black Americans and hippies, according to a high-level adviser.

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and Black people,” Nixon’s domestic policy adviser, John Ehrlichman, said in 1994.

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Blacks, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

Nixon’s so-called “drug war” started out largely as a public-health crusade. Over time, it would be reshaped into punitive actions, mainly by later administrations, particularly President Ronald Reagan, whose wife Nancy underscored his front-line offensive with the words “just say ‘no’ to drugs.’”

The proportion of Black Americans the war on drugs has put in jails and prisons far exceeds their percentage of the U.S. population.

[Police photo]

Some war.

When Prime Minister Stephen Harper declared a “war on crime,” Statistics Canada’s records showed that violent and non-violent crime rates alike had already been on the decline for more than a decade. Yet his government warned of a crisis and imposed a series of punitive measures, including mandatory sentencing.

Craig Jones, one-time head of the John Howard Society of Canada, described the campaign as “penal populism,” or “the politicization of criminal justice and drug policy for short-term electoral advantage combined with a sympathetic—but largely content-free—discourse about ‘victims.’”

In a 2015 essay for Policy Options, the digital magazine of the Institute for Research on Public Policy, Jones said all it managed to do was degrade Canada’s justice system.

“It was all ideology all the time, characterized by open hostility toward evidence, disdain for harm reduction, and contempt for science, and disinterest in what works to limit the damage from incarceration, drug prohibition and drug use,” he wrote.

“The Harper government practised—almost as a matter of principle—unwillingness to consider the consequences of their anti-science, anti-evidence, anti-best practices agenda. It was the worst of times during which this country tumbled from its world-leading status as a correctional reform leader to importing the worst American justice errors.

“Among correctional practitioners, it was nine years of ‘bumper sticker’ and ‘feel good’ dogma unconcerned with an appreciation of downstream consequences beyond consolidating the government’s electoral base.”

It worked for Harper, at least: He won elections in 2006, 2008 and 2011, serving as prime minister for more than nine years. But he left behind an overcrowded, underfunded prison system.

These days, alarmists speak of a phantom “war on Christmas,” seen by some as a dog whistle by bigots seeking to stoke fears that non-white, non-Christian immigrants are stealing Western religion and culture.

The term was popularized by the likes of American conservative commentators Bill O’Reilly and Peter Brimelow in the early 2000s.

They claimed the term “Christmas” and associated religious references were increasingly being censored, avoided or discouraged by advertisers, retailers, schools and other public and secular organizations.

For two years now, the world has been waging “war” on COVID-19.

With the increasing popularity of the more egalitarian “holidays,” some took umbrage and, stoked by loudmouths like Brimelow and O’Reilly, denounced the term as a capitulation to political correctness.

For almost 20 years now, conservative media and some religious groups have periodically been calling for boycotts of some prominent secular organizations, particularly retail giants, demanding that they use the term “Christmas” rather than solely “holiday” in their marketing and advertising campaigns.

To the mainstream, however, the controversies that continue to this day seem a tempest in a teapot—simple, in most cases voluntary, measures of tolerance and accommodation in an evolving land. Hardly a war.

“There is no war on Christmas; the idea is absurd at every level,” Huffington Post commentator Jeff Schweitzer declared in 2014. “An 80 per cent majority can claim victimhood only with an extraordinary flight from reality.”

Belief in the “war on Christmas” is stoked to this day by broadcasters such as Tucker Carlson of Fox News.

[Fox News/YouTube]

“Wars” have long been waged against sickness and disease. The war on cancer. The war on heart disease. The war on AIDS.

For two years now, the world has been waging “war” on COVID-19.

“I’m a wartime president,” Donald Trump said in March 2020, nine days after declaring a national emergency. “This is a war. This is a war. A different kind of war than we’ve ever had.”

Addressing the House of Commons on April 11, 2020, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau invoked memories of war in a speech about “the trials that shaped our country.”

As he spoke, the pandemic was escalating in Canada, a great unknown that was approaching 26,000 cases and 800 deaths. Canadians from coast to coast were shut inside their homes, while doctors, nurses and other health-care workers were staging a heroic defence against the onslaught.

Minimum-wagers, such as grocery store clerks, restaurant workers and delivery drivers, were pressing on to provide essential services and maintain some semblance of functionality as the country’s economy shrank.

The House was about to vote on a massive spending package aimed at easing the economic impacts of COVID-19 and, while Trudeau said the crisis surrounding the pandemic was not a war, the ultimate conflict was implied throughout his address.

“Why do we talk about medical professionals as if they are soldiers on the front lines of a war?”

“As I stand here today, I think of the young men who died taking Vimy Ridge,” Trudeau said on the 103rd anniversary of Canada’s seminal battle. “I think of the Greatest Generation who grew up during the Depression and fought through World War II.

“They fought for us all those years ago. And today we fight for them. We will show ourselves to be worthy of this magnificent country they built. And for them and for their grandchildren, we will endure. We will persevere. And we will prevail.”

But many commentators and medical professionals consider the war analogy—in the case of the coronavirus, at least—inappropriate.

“Why are we tempted to treat COVID-19…like a terrorist force, to not ‘let the virus win?’” culture reporter Alissa Wilkinson wrote for Vox during the first spring of the pandemic. “Why do we talk about medical professionals as if they are soldiers on the front lines of a war, rather than scientists and practitioners studying and caring for the health of others? Is it possible that saying ‘we are at war’ prevents us from seeing all the ways we can both end this pandemic and prepare for the next one?

Some commentators and medical professionals consider comparing the fight against viruses to war inappropriate. [Mstyslav Chernov/Wikimedia]

One problem with the war metaphor, she noted, is that it can stigmatize people with the disease because they can’t “fight it off.”

“Even today,” said Lisa Keranen, who studies medical rhetoric surrounding viruses and other biological threats, “we talk about people whose immune systems are ‘weaker’ because they can’t fight off COVID-19.

“There’s almost a smuggling of some implicit blame in there for someone who is a victim of a disease.”

In the 2016 movie Arrival, linguist Louise Banks (played by Amy Adams) is tasked with teaching aliens to speak English. She explains to a military commander why it’s not just the words she teaches, but also how she frames the teaching and applies grammar.

“Let’s say that I taught them chess instead of English,” she says. “Every conversation would be a game. Every idea expressed through opposition, victory, defeat. You see the problem? If all I ever gave you was a hammer…”

“Everything’s a nail,” the commander interjects, grasping her meaning.

In fact, the problems that confront society are more often puzzles, the solutions to which demand dexterity, finesse and degrees of elegance, not the bludgeon of mighty force.

Often, as in the war on AIDS and possibly now on COVID-19, there is no “victory,” but measures of mitigation and control with which people eventually learn to live.

Advertisement