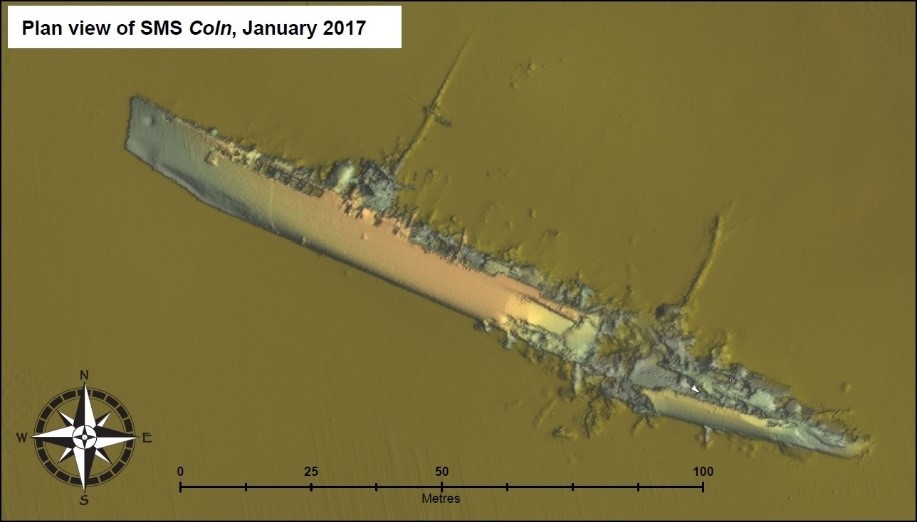

A digital terrain model of the wreck of SMS Cöln, taken at Scapa Flow in January 2017.

[Innes McCartney]

“For we couldn’t leave her there, you see, to crumble into scale,” he sings. “She’d saved our lives so many times, living through the gale.”

The nature of seafaring, the dependence on a relatively tiny refuge perpetually (hopefully) afloat on vast and volatile waters, breeds in mariners a special affection for the crafts they sail in. It is in part why seamen have always referred to their ships in the feminine— ‘she’ and ‘her’ —for, the story goes, they are motherly, womb-like, life-sustaining vessels, protecting and nurturing their crews through good times and bad.

In some ways, then, losing a ship is not unlike losing a loved one, at least for those who have sailed, and survived. For owners— the insured ones whom Rogers describes as “laughing, drunken rats” —not necessarily so much.

As with comrades and friends, in the annals of sea warfare, ships come and go. A sparse few are literally raised from the ocean depths. Some— the Titanic, a peacetime example —develop lives of their own long after they’re gone.

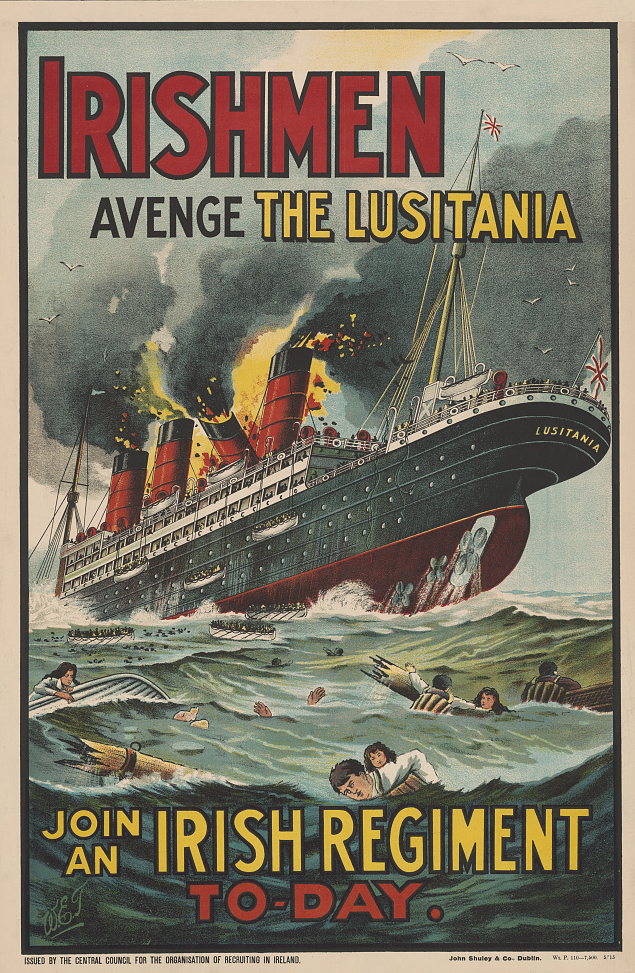

Incidents like the 1915 sinking of the ocean liner Lusitania by a German U-boat off Ireland, in which 1,195 men, women and children died, are manipulated to boost popular support for the cause and help feed the war machine, giving lost ships of a particular kind life after death.

“Remember the Lusitania!” proclaimed First World War recruitment and fundraising posters in what became a WW I battle cry.

While naval and merchant crews’ attachments to their homes away from home are as strong or stronger than those of many seafarers, however, the need for dutiful survivors to move on after they’re gone is relentless. Prudence and practicality take precedence in wartime, for all manner of reasons.

So it was on June 21, 1919, when German sailors, interned over seven months at Scapa Flow off Scotland’s Orkney Islands with what was left of their WW I navy, unceremoniously sank 52 of 74 of their own vessels.

Armistice talks weren’t going well, and German Admiral Ludwig von Reuter feared the British would seize the ships unilaterally, or the German government would reject the Treaty of Versailles, resume the war effort, and pit its forces against a fleet of its own ships fighting under Allied flags.

A poster calls Irishmen to arms to avenge the 1915 sinking of the liner Lusitania.

[Reddit]

In some ways, then, losing a ship is not unlike losing a loved one, at least for those who have sailed, and survived.

At 11:20 a.m. on that Saturday morning, von Reuter sent a coded signal to his fleet by flag and searchlight, ordering his crews to scuttle their ships.

They immediately began smashing internal water pipes and opening seacocks, flood valves and sewage drains.

Portholes had been loosened ahead of time, watertight doors and condenser covers were left open and, in some ships, holes had been bored through bulkheads, all to help along the spread of water and speed the sinking process.

One German skipper recorded that seacocks had been heavily lubricated and preset on a hair-turning, while large hammers were placed beside valves.

There was no noticeable effect until noon, when the ship Friedrich der Grosse began listing heavily to starboard and all the ships hoisted the Imperial German Ensign at their mainmasts. Crews then began abandoning ship.

Much of the British fleet assigned to guard the vessels was away on exercise that day. The British commander, Admiral Sydney Freemantle, learned of the scuttling about 40 minutes after it began and cancelled his squadron’s exercise at 12:35 p.m., steaming at full speed back to Scapa Flow.

Only the largest ships were still afloat by the time they arrived at 2:30. The last to sink was the battlecruiser Hindenburg at 5 p.m. By then, 15 capital ships were at the bottom; only one remained afloat. Five light cruisers and 32 destroyers were also sunk. Nine German sailors died and about 16 were wounded by panicked guards.

Intervening vessels were able to beach some of the sinking ships. A few others were eventually raised after local complaints that they were a hazard to navigation. But the rest of the sunken fleet lay undisturbed, their salvage deemed untenable at a time when scrap metal markets were glutted with the detritus of war.

Until, that is, British entrepreneur Ernest Cox came along and paid the Admiralty 250 pounds (worth about 14,000 pounds in 2023, or C$25,000) for 26 sunken German destroyers. Cox raised the 26 along with two battlecruisers and five battleships before he sold his company and retired as “the man who bought a navy.”

The new salvagers, Alloa Shipbreaking Company, later to become Metal Industries Group, raised five more cruisers, battlecruisers and battleships before the Second World War ended the enterprise. Seven of the wrecks still lie in deep water at Scapa Flow, diveable by permit.

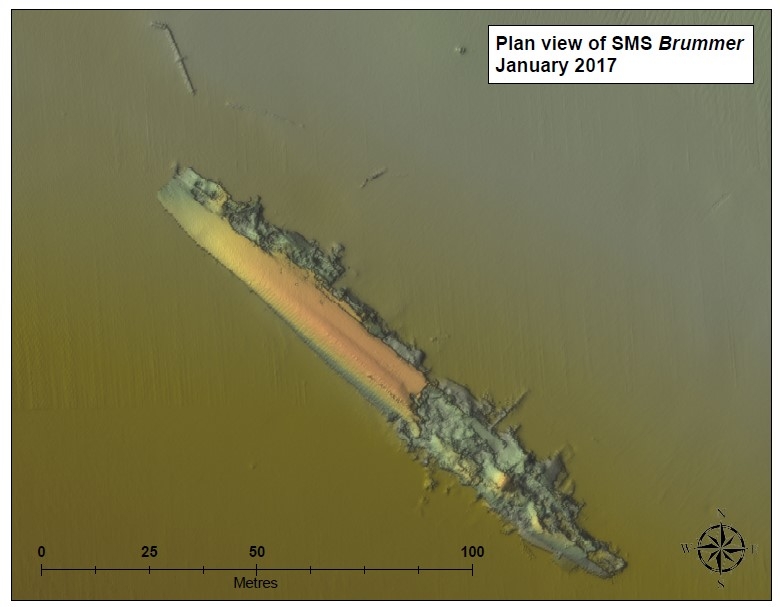

A digital terrain model Plan View of SMS Brummer, scanned in January 2017. The wreck shows evidence its engine rooms have been salvaged, a consistent feature of the light cruiser wrecks at Scapa Flow.

[Innes McCartney]

British entrepreneur Ernest Cox paid the Admiralty 250 pounds (worth about 14,000 pounds in 2023, or C$25,000) for 26 sunken German destroyers.

During the war-long Battle of the Atlantic between 1939 and 1945, the Allies alone lost 175 warships and some 3,500 merchant vessels, along with 72,000 sailors and merchant seamen.

It is generally agreed that 1,131 U-boats entered service under the pennant of Nazi Germany during WW II, but how many were actually lost is another matter. The most-accepted figures of wartime losses range between 765 and 785 U-boats.

Of all those, just one—U-31—was raised and returned to service during the war, only to be sunk again a few short months later.

U-31 was conducting sea trials off Germany on March 11, 1940, when a Blenheim of 82 Squadron, Royal Air Force, caught it on the surface and attacked, dropping four semi-armour-piercing bombs.

Two found their mark, damaging the sub’s compressed-air tanks. Uncontrolled compressed air flooded into the boat as it crash-dived; 56 of its 58 crew were killed outright. Two others on the conning tower were washed overboard and drowned.

U-31 had already conducted five patrols, sinking 10 Allied ships and damaging a British battleship before it became the war’s first U-boat to be sunk by aircraft.

Four days later, salvage crews raised the sub from about 18 metres of water in Jade Bight, a channel to the North Sea off the German naval centre of Wilhelmshaven. They towed it into port, repaired it and returned the boat to service on July 30.

U-31 sailed two more patrols, survived three attacks, and sank three more Allied merchant ships before it was sunk again, this time northwest of Ireland on Nov. 2, 1940, by depth charges from the British destroyer HMS Antelope.

The attacking ship picked up 43-44 survivors from the boat’s 46-man crew; at least two others died. U-31 was gone for good.

U-31 sinks right astern of HMS Antelope on Nov. 2, 1940.

[Royal Navy]

U-31 was raised and returned to service during the war, only to be sunk again a few short months later.

Three primary factors saved the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor during the Japanese surprise attack of Dec. 7, 1941:

- all three aircraft carriers based at the Hawaiian port were at sea when 353 Japanese aircraft attacked in two waves starting at 7:48 a.m. on a Sunday morning; they would quickly change the course of the entire war;

- the attackers overlooked critical infrastructure, including the power station, drydock, shipyard and maintenance, fuel and torpedo storage facilities; the submarine piers and headquarters with its decoding room were also spared;

- of 102 ships stationed at Pearl Harbor at the time of the attack, 69 were undamaged, 26 were damaged and seven were sunk; only two, the battleships Arizona and Utah, a training vessel, were deemed total losses and written off.

The battleship Oklahoma was stripped of usable materials and ultimately sank while in tow to California after the war. The four other sunken ships were raised and returned to service by mid-1944. In fact, all but three ships damaged or sunk in the Pearl Harbor attack were repaired and returned to war service.

More than 2,400 Americans, including 2,008 sailors, had been killed. Another 1,178 were wounded. But the U.S., a reluctant participant whose lend-lease program helped save Britain, was now in the fight wholesale, and “Remember Pearl Harbor” became a rallying cry of the Pacific War.

The recovery work started immediately. Most of the smaller ships and three of the battleships— Pennsylvania, Maryland and Tennessee —were either returned to service or refloated and taken to the continental U.S. for final repairs.

The efforts were nothing short of gargantuan. The hull of the USS Nevada was riddled with holes, including a big one. The battleship’s interior was flooded and many of its compartments were burned out.

Nevada’s overhaul was completed in October 1942. The ship provided fire support during the liberation of Attu during the Aleutian Islands Campaign, then joined North Atlantic convoy duty. Nevada provided fire support for the D-Day invasion and Normandy campaign of 1944.

Fitted with bigger guns during its overhaul in Washington state, the ship fired shells up to 31 kilometres inland at Normandy in efforts to break up German concentrations and counterattacks. It was straddled by counter battery fire 27 times and never hit.

The Pearl Harbor attack left the battleship California in even worse shape than Nevada, holed by two torpedoes and a bomb and fully submerged to its main deck.

Salvage teams enclosed the ship in a wooden cofferdam— a watertight enclosure pumped dry to permit recovery work below the waterline —and the effort to refloat it began in earnest. Divers closed manhole covers and doors. Once afloat, the ship was transported to the Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Wash., where it was rebuilt and returned to the combat fleet in early 1944.

The USS West Virginia was the most severely damaged of the surviving battleships. By official U.S. Navy accounts, its port side had been ravaged by eight— yes, eight—Japanese torpedoes and its rudder was ripped off by another.

Salvagers removed more than three million litres of fuel oil and the ship’s vast cache of ordnance before it could be patched and refloated. The work continued at Pearl Harbor until April 1943, when it was taken to Puget Sound for an extensive refit. The West Virginia returned to service in July 1944.

A small boat rescues a sailor from Pearl Harbor waters alongside the burning USS West Virginia. The ship was sunk by six Japanese torpedoes and two bombs. [U.S. Navy/Library of Congress]

All but three ships damaged or sunk in the Pearl Harbor attack were repaired and returned to war service.

The Pacific War shifted abruptly at the subsequent battles of the Coral Sea, where the Japanese and the Americans lost a carrier each, and Midway where, six months after Pearl Harbor, U.S. naval aircraft sank four Japanese fleet carriers and a heavy cruiser. The Americans lost the carrier Yorktown to Japanese aerial bombardment and air-dropped torpedoes at Midway.

Battle deaths numbered 3,057 Japanese to 307 Americans. The fighting revolutionized the use of carriers and seaborne aircraft in naval warfare.

Military historian John Keegan called Midway “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare,” while naval historian Craig Symonds described it as “one of the most consequential naval engagements in world history.”

There was much bloody fighting ahead as U.S. Marines island-hopped northward, but the tide of the Pacific War had taken a dramatic turn from which the Japanese would never recover.

The wrecks from both battles lay unexplored until 1998, when Yorktown was confirmed about 1,600 kilometres northwest of Honolulu. In less than a week in 2019, explorers found the wrecks of the Japanese carriers Kaga and Agaki in 5,490 metres of water.

The USS Lexington, the carrier sunk during the Battle of the Coral Sea, was found by the late American explorer and philanthropist Paul G. Allen and his research vessel R/V Petrel in 2018 some 3,000 metres below the ocean surface, about 800 kilometres east of Australia. The ship’s aircraft were still clearly identifiable.

Other notable victims of sea battles have been discovered in recent decades, including the British battleship HMS Hood, found in three sections 2,845 metres down in 1981. The bow was on its side, the mid-section upside down and the stern still speared into the seabed 40 years after it was lost in the Battle of the Denmark Strait.

The German battleship that sunk it, Bismarck, was scuttled after suffering catastrophic damage. It was found in 1989, sitting upright in some 4,572 metres of water, about 1,000 kilometres west of Brest, France. In fact, inspection of the Hood wreck solved the mystery of how it was lost: its aft magazines exploded after a direct hit from Bismarck’s guns.

Close to home, the tankers British Freedom (the master was lost, 57 crew survived) and Athelviking (the master and three crew lost, 47 survived) were torpedoed and sunk by U-1232 under Kapitän zur See Kurt Dobvratz on Jan. 14, 1945, just off the mouth of Halifax Harbour. Both were stripped of much of their brass and memorabilia after they were found in about 60 metres of water during the 1990s.

HMCS Clayoquot, a minesweeper, was torpedoed off Halifax by U-806 on Christmas Eve 1944. Eight crew died. The ship lies in pristine condition 91 metres below the surface on the edge of a large channel at the entrance to the harbour, its foredeck gun still in place and stern destroyed by the strike.

The deepest shipwreck ever found was the USS Samuel B Roberts, a destroyer escort sunk in October 1944 during the Battle off Samar in the Philippine Sea and discovered 6,895 metres down in 2022.

The aircraft carrier USS Lexington explodes during the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 8, 1942.

[U.S. Navy]

In the fall of 1942, two U-boats—U-513 and U-518—sunk four ore carriers off Bell Island, Nfld., in separate attacks two months apart. Sixty-nine merchant crewmen were killed, and an errant torpedo destroyed a loading dock.

The ships lie within a 5.5-kilometre radius at the anchorage, their holds still laden with iron ore from the Bell Island mines. The cargo is even spilling out of the gaping torpedo hole in PLM 27.

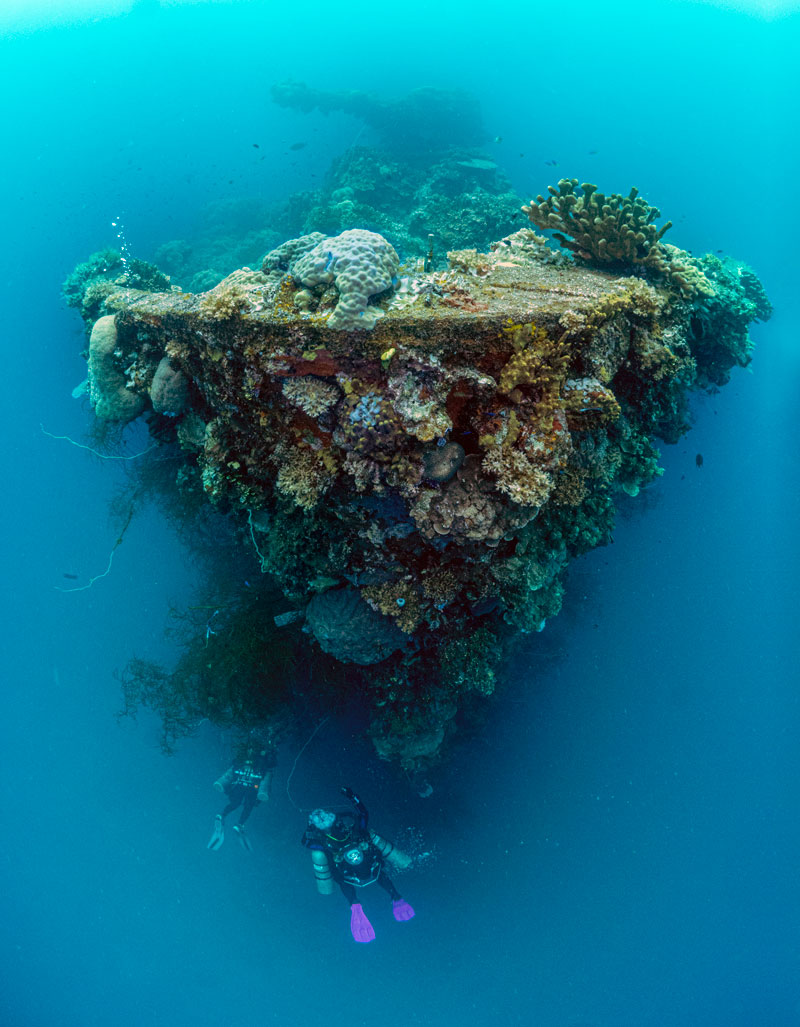

“Beautiful, colourful life just grows all over them,” said Canadian undersea explorer Jill Heinerth, who has dived on the wrecks more than 20 times. “The first time I saw the barrel of one of these defensive guns with anemones sprouting out of the end, I think that touched me more than anything. This used to spit salvos of ammunition and now it’s just growing this bouquet of anemones. It’s incredible.”

On the other side of the world, Allied sailors know the stretch of water at the southern end of what was called Savo Sound in the Solomon Islands as “Ironbottom Sound.” Dozens of ships and planes sank there during the Battle of Guadalcanal in 1942-43.

The site is now a divers’ paradise, along with the former Truk Atoll in the Pacific islands of Micronesia. At the latter, now called Chuuk Lagoon, Heinerth dove on the wrecks of dozens of ships, aircraft, even the remains of a small Japanese submarine.

The site in the Caroline Islands was Japan’s main South Pacific base during the Second World War, staffed by almost 28,000 personnel of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, tankers, cargo ships, tugboats, gunboats, minesweepers, landing craft and submarines were anchored in the lagoon. Japan withdrew its larger warships before the Americans attacked early on the morning of Feb. 17, 1944.

The operation, known as Hailstone, lasted three days. U.S. carrier-based planes sank 12 Japanese warships and 32 merchant vessels. They also destroyed 275 aircraft, mainly on the ground.

Canadians were part of a force of British Pacific Fleet ships that staged a second attack, Operation Inmate, in June 1945. What they left behind is now dubbed “the world’s biggest ships’ graveyard.”

“The wrecks are extraordinary,” said Heinerth. “There are dozens…and they were all sunk simultaneously, basically, and they’ve all become incredible artificial reefs. The colour is unbelievable.

“They’re very, very intact, many of these wrecks, so we can easily penetrate some great distances inside of them.”

Divers explore the bow of the Fujikawa Maru in the South Pacific.

[Courtesy Jill Heinerth/ INTOTHEPLANET.com]

The contrast between the shipwrecks is evident, reports the dive website masterliveaboards.com. Most of the Solomons ships went down during active fighting.

“The wrecks in Truk [Atoll] are relatively pristine as they were sitting still during the bombings,” said Shaz Kozak, Solomons master operations manager. “In the Solomons, you will see clearly the battle wounds and war damage on the wrecks. This is what makes [the] Solomon wrecks so interesting to dive and explore.”

The variety of ships differs, as well. In Truk Atoll, all the wrecks are Japanese. At Iron Bottom Sound, there’s a large proportion of American hulks among Japanese and New Zealand vessels lying on the bottom.

Advertisement