Commander of the Kriegsmarine in 1943, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder told senior staff that “without the success of the navy there can be no final victory.” He would be proven right. [BUNDESARCHIV, BILD/146-1980-128-63/CC-BY-SA 3.0]

Documents seized by Allied forces at the end of the Second World War cast a light on the continuing struggle Hitler’s senior military officers had in waging war and reasoning with their wilful boss.

The dictator was already fed up with what he felt was the Kriegsmarine’s underperformance in the Mediterranean and the North Atlantic, but his anger reached the breaking point after a failed attack on an Allied convoy in the Barents Sea in December 1942. He ordered Grand Admiral Erich Raeder to submit a plan for docking the navy’s big ships. Raeder came back days later with guns blazing.

“If Germany’s large ships are decommissioned, the repercussions will be disastrous not only for our own situation but for the overall naval strategy,” Raeder said in a 5,000-word memorandum submitted Jan. 15, 1943, about two weeks after the sea battle in which some of his destroyers mistook Allied ships for their own. “There will be speedy and serious consequences in the other theatres for our allies.

“If we withdraw our threat from the Atlantic,” he continued, “the enemy will be able to concentrate his power somewhere else, and no effort on his part will have been required for the achievement of such a decisive success.

“He will be able to use this situation to settle conclusively the Mediterranean problem; or he can mass all the power of his best ships for a decisive blow against the Japanese fleet. In either event, he will regain the initiative which he had lost or which at least had been seriously limited.

“It is impossible to foresee the consequences.”

Der Führer was unmoved.

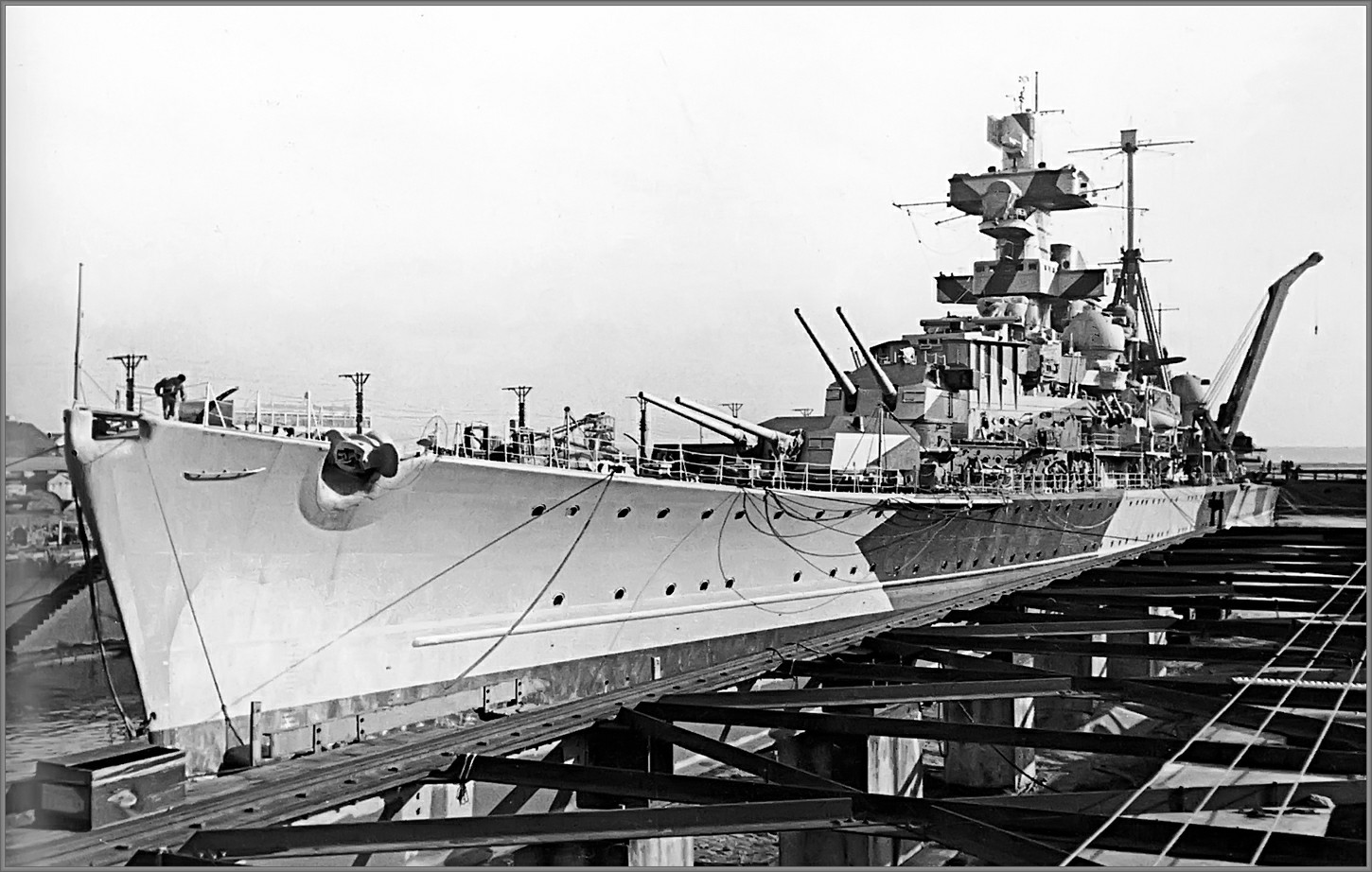

The German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper in Brest in 1941. The ship was scuttled at its moorings in Kiel, Germany, in 1945 after a Royal Air Force bombing raid. [WIKIMEDIA]

The memorandum was prepared by several top-ranking officers in the Operations Division of the German Naval Staff. The final draft shows careful corrections made by Raeder himself—most of them aimed at avoiding any room for misinterpretation that could offend the notoriously temperamental Hitler.

Raeder also deleted detailed calculations related to the possible reallocation of guns and other equipment from dismantled ships. Yet where the memorandum spoke of the role of the German Navy in the Second World War, a U.S. intelligence assessment said Raeder’s final corrections “served to bring out his point of view in the clearest and most outspoken form.”

He attached the memorandum to a brief letter addressed to “The Führer and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.” The letter, as Allied intelligence described it, constituted the last plea of the Kriegsmarine.

“Decommissioning of the large surface vessels will be a victory gained [and will] cause joy in the hostile camp, and deep disappointment in the camp of our allies, especially Japan,” Raeder wrote. “It will be viewed as a sign of weakness and of a lack of comprehension of the supreme importance of naval warfare in the approaching final stage of the war.”

The memorandum itself was entitled The Role of the German Naval Surface Forces in the War Effort of the Tripartite Powers.

In it, Raeder explains that the naval forces of Nazi Germany were designed and built to strike at the weak points of hostile naval powers—particularly Anglo-American sea communications. “The very existence of the English people rests on these communications, which also form the prerequisite to the entire British war effort,” says the document. “The enemy is superior in manpower, raw materials, and industrial potential. His chief problem is to maintain the vital shipping lines to Russia, so that he can transport men, materiel, and supplies to the points where he wishes to bring his offensive power to bear.”

This required enough ships with sufficient fighting power and cruising range to do the job. But German construction had only begun in earnest in 1939, he noted, and the building of big ships takes years.

“In order to increase quickly the number of our submarines, it was decided to complete construction of only those ships which were already in the final building stage. Construction of the other big ships was stopped.

“By this decision the German Navy was prevented from cutting the British sea communication lines in the course of the Greater German War for Freedom, and thereby to put a speedy end to the war. All emphasis of the construction program had to be placed upon submarines which were able to operate on the oceans against enemy shipping even without the support of large surface ships.”

Auxiliary cruisers were assigned to operations in remote areas; light naval forces, destroyers, torpedo boats and PT boats operated in enemy coastal waters, and the large ships of the fleet were committed to offensive operations against overwhelming enemy forces. However, the occupation of Norway consumed Germany’s larger naval resources.

“Our big ships were not called upon to attack enemy forces encountered at sea or to seek an engagement,” said the document. “Every loss weighed incomparably more on our side than on the side of the far superior enemy, even any minor damage that might arise from the hazards of war at sea, such as a reduction of speed.”

German Admiral Karl Dönitz (in dark coat), followed by Colonel-General Alfred Jodl (at left) and Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer, under arrest by British officers in 1945. [CAPT. E.G. MALINDINE/NO. 5 ARMY FILM AND PHOTOGRAPHIC UNIT/IWM]

“A German naval task force properly distributed along the western coast of France would have constituted the most effective obstacle for an Allied landing in North Africa, but for this we lacked sufficient strength,” said the memorandum.

“Since the spring of 1942 the command of our fleet had to limit further operations due to the lack of sufficient air support for reconnaissance and escort, and since it was impossible to provide our ships with the additional fighting power of carrier-based aircraft.

“Nevertheless, the opportunity still exists for our ships to keep on a sharp lookout and to await a moment favourable for an engagement. Even in the absence of sufficient air reconnaissance and air cover, favourable weather conditions and the element of surprise can be utilized at any time to achieve success.”

Dismantling the nucleus of the German fleet—the big ships Tirpitz, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Scheer, Luetzow, Prinz Eugen, and Admiral Hipper—would “constitute a bloodless victory for the enemy,” the memorandum said.

“For us, the result would be that the enemy could operate in our coastal waters at his own discretion. It is not possible to maintain air forces in sufficient strength and in constant readiness for defence, especially in northern waters. Even if this were possible, weather conditions such as low ceiling would prevent their successful operation at times.

“We would practically be offering our coastline to the enemy,” the document warned. “Light naval units alone cannot ward off such operations.”

The German battleship Tirpitz in 1941. [Wikimedia]

- About 300 officers and 8,500 enlisted men would become available—less than 1.4 per cent of naval personnel.

- 125,800 tonnes of iron would be obtained if the ships were scrapped—less than 1/20 of the German monthly requirements.

- Savings in raw materials, fuel, yard facilities, shipyard workers, etc. would be consumed in large part by the process of mounting the ship guns as shore batteries.

- Fifteen batteries could be constructed from the newly accessible guns, the first of which would not be ready for action for a year after the order to scrap the ships, the last of them after 27 months.

- Scrapping the big ships would require the work of 7,000 men in five large shipyards for one-and-a-half years.

- Benefits to the U-boat program would be slight. Of 300 officers available for reassignment, only about 50 would be gained for the submarine arm. Others would be too old or otherwise unsuitable.

- If all the scrapped ship iron was used exclusively for U-boat construction, seven more submarines per month could be built, provided 13,000-14,000 specialized workers could be allocated for the job.

“The disappearance of our nucleus fleet will have the most serious political and psychological repercussions in the nations, among our allies and among the neutrals,” said the paper. “Our nation…will conclude that we have abandoned all hope of winning this war by decisive naval operations.

“Our allies, and especially Japan, have felt the full impact of the enemy’s sea power, and they have fought it. They would not be able to comprehend our voluntary abandonment but would see in it a serious sign of weakness of the German war effort.

“The neutral powers too can evaluate a weakening of our naval strength only as a sign of declining strength. Yet to the enemy the disappearance of our warships will represent a political triumph.”

In conclusion, Raeder’s report said it is “impossible to foretell where and how soon the course of the war may demand the exercise of naval power for decisive intervention. It will be our own fault if at such a decisive hour our big ships are lacking, and then it will be too late.”

Raeder resigned two weeks later, on Jan. 30, 1943. He was named Admiral Inspector, a ceremonial office. Dönitz would go on to succeed Hitler and surrender 16 months later.

Raeder was captured by Soviet troops on June 23, 1945, and imprisoned in Moscow. He stood trial at Nuremberg, where he was sentenced to life for conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity; along with planning, initiating, and waging wars of aggression; and crimes against the laws of war.

He carried on a constant feud with Dönitz in prison before he was released on health grounds in September 1955. He died in Kiel on Nov. 6, 1960, and was buried in the city’s Nordfriedhof (North Cemetery).

Advertisement