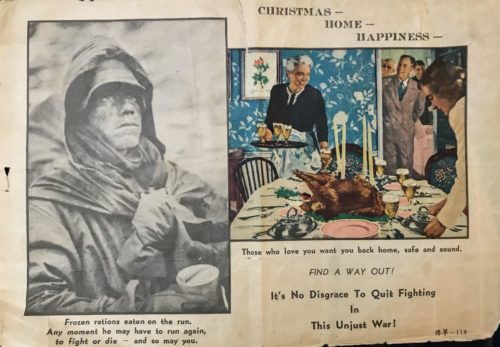

The Chinese military dropped this psychological-warfare pamphlet on Canadian troops in Korea in December 1951. [Courtesy of Louis Bailey]

“That’s what we got at Christmastime,” said Bailey, 92, handing over the one-page document.

On one half of the remarkably preserved paper is a now-famous David Douglas Duncan photograph of a dirty, miserable U.S. Marine huddled with his meagre rations against the cold of a winter near Chosin. On the other is a Rockwellian-style image of a happy family assembling around a table laden with Christmas turkey.

“Frozen rations eaten on the run,” it says below the frontline photograph, which originally appeared in the weekly Life Magazine before Chinese propagandists seized on it as a tool of manipulation.

The hooded marine is holding a can of frozen beans, his 1,000-yard gaze emblematic of his unit’s December 1950 retreat after they had been cut off by Chinese forces at the Chosin Reservoir northeast of Pyongyang.

“Christmas cards” suggested sweethearts back home were spending the holiday with another man.

When Duncan, himself a former U.S. Marine, asked the soldier what he wanted for Christmas, he famously replied: “Give me tomorrow.” The retreat marked the complete withdrawal of the United Nations-sanctioned forces from North Korea.

It was all great fodder for the communist Chinese, who were fighting alongside the North Koreans to unite North and South. The copy and the contrasting images aimed to undermine morale and resolve among the American, Canadian and allied forces on the peninsula, so far from home at their most vulnerable time of year.

“Any moment, he may have to run again to fight or die—and so may you,” warns the flyer.

On the other half of the page, the words ‘CHRISTMAS—HOME—HAPPINESS’ appear above the illustration depicting an immaculately set dinner table and the smiling faces of a gathering family.

“Those who love you want you back home, safe and sound,” it says below the image. “FIND A WAY OUT! It’s No Disgrace To Quit Fighting In This Unjust War!”

According to Bailey, the Canadians saw the flyers for what they were—a ham-handed attempt at sowing depression and discontent among those attempting to stop communism’s advance far from home and family.

“It’s a good souvenir,” he said dismissively. “I don’t think there’s too many of them around. Nobody kept them.”

A German leaflet dropped during the Second World War attempted to demoralize Allied troops. [www.psywarrior.com]

Even ancient warlords recognized the value in weakening the morale of their enemies and embarked early on to find soft spots to poke.

During the Battle of Pelusium in 525 BC, Persian forces used cats and other animals as a psychological tactic against the Egyptians, for whom felines held great religious significance. Such practices helped spawn the truism “know thine enemy,” attributed to Sun Tzu and his 512 BC military treatise, The Art of War.

Some methods lacked nuance.

In the 13th century AD, Ghengis Khan would warn villages in advance of plans to unleash his Mongolian hordes upon them if they did not surrender first. His warriors would massacre entire populations that refused his offer, and he would ensure that news of their fate would reach his next objective, inevitably moving its residents to think twice about following their neighbours’ example.

Similar practices continue to this day, 800 years on—from mass executions of villagers by Nazi occupiers in Second World War France, to the 1968 Mỹ Lai massacre by American troops in Vietnam, to the butchery by ISIS fighters in modern-day Persia—all motivated by the desire to bring others onside through fear.

American pilots with leaflets to drop in the First World War. [www.psywarrior.com]

English novelist and playwright Edward Bulwer-Lytton wrote “the pen is mightier than the sword” in 1839 and, by the First World War, enough rank-and-file soldiers were literate that words and pictures became the preferred form of messaging by those intent on winning, or at least changing, the hearts and minds of their enemies.

It proved a watershed moment in warfare, and forces on both sides sought ever-higher ways of penetrating and compromising the psyches of their rivals on the front. By then, the wheels of propaganda and psychological warfare were greased by mass-circulation printing presses and airborne leaflet drops.

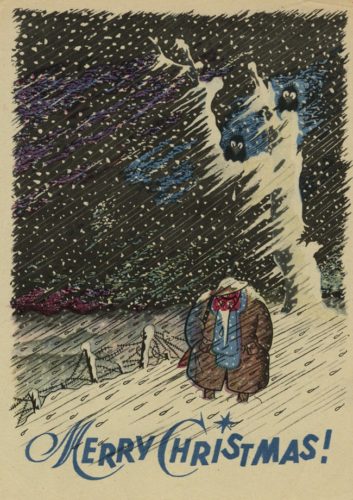

(Click on photo to enlarge) Fake letters (top) were circulated describing unhappiness at home. This Christmas card (above left) was used by Japan against American forces on Guadalcanal, northeast of Australia, in December 1942. Britain produced this Christmas card (above right) depicting Hitler as Santa Claus with the words “Hunger” and “War.” [www.psywarrior.com]

The famous Christmas truce of 1914 was borne of the misguided assumption by the trench-bound soldiers of both sides that the Great War would not last, that their differences were not that stark, and that all would be well again by spring.

“The generals, outraged by the willingness of their men to fraternize with the enemy, issued harsh orders prohibiting continuation of the truce,” wrote Therea Blom Crocker of the University of Kentucky in a 2012 thesis.

“And the soldiers, now reluctant to fire upon opposing troops, had to be coerced into resuming the war, and in some cases were even punished for their participation in the ceasefire.”

But by the following Christmas, with the advent of poison gas and two brutal battles at Ypres along with many other slaughters behind them, the season of peace and goodwill had become a weapon in the arsenals of both sides.

Exchanges of rations and cigarettes, family picture displays and soccer matches in no man’s land were verboten. Instead, “Christmas cards” suggested sweethearts back home were spending the holiday with another man.

By war’s end, British intelligence alone had dropped almost 26 million leaflets on German lines, including postcards from German PoWs detailing the good food, warm beds and humane treatment they were receiving at the hands of their captors.

“Christmas is a time where, traditionally, we think about coming together.” But radio had a more far-reaching effect.

The practice was so effective that the Germans began shooting captured leaflet-dropping pilots, prompting the British to develop the unmanned leaflet balloon in 1917. Some 48,000 were deployed in the last 18 months or so of the war.

Contrary to regulations, soldiers kept at least one in seven leaflets, despite the threat of severe penalties for not handing them in. General Paul von Hindenburg acknowledged that “unsuspectingly, many thousands consumed the poison.”

German PoWs—many uneducated and unworldly—did admit to disillusionment at the suggestion conveyed by the leaflets that they were mere cannon fodder.

Indeed, “cannon fodder” was a favourite term of manipulation for both sides, although something was lost in translation in this message, entitled “Think It Over,” dropped on American lines late in the First World War:

“You have left behind you all that is dear to you and come to France to fight the Germans,” it said. “Until the English wanted you for cannon food you never knew that the Germans were your enemies.”

A leaflet dropped on “ye Britons” in November 1918 suggested “there might be a truce to fighting now and peace by Christmas if you accept Germany’s liberal offers.”

“Would you not rather save your lives and your health, thereby furthering the happiness of your families and dear ones at home, than to further the greedy ambitions of lying war agitators?”

It was the Germans who capitulated a week later.

This German propaganda leaflet targeted the British in 1944. [www.psywarrior.com]

“Every American theater commander, given the choice of using psychological warfare or not…did choose to use it,” wrote Paul Linebarger in his 1948 book Psychological Warfare. “Every major government engaged in the war used psychological warfare.”

And no wonder. The propaganda aimed at soldiers on the front “fed off that fear and anxiety of separation”—feelings especially strong around Christmas, said historian Tim Cook of the Canadian War Museum, author of 13 books on war.

“War we often think about as service, sacrifice and fighting, and coping and enduring, but it’s also about separation—separation from your loved ones for months or years on end,” said Cook in an interview with Legion Magazine.

“Christmas is a time where, traditionally, we think about coming together and I think that playing off that could be quite difficult for young guys, who are especially going through particularly difficult situations.”

In the lands of “Stille Nacht” (“Silent Night,” Austria) and “O Tannenbaum” (“O Christmas Tree,” Germany)—the lands of Kris Kringle—Christmas is particularly close to the heart, a fact that was not lost on wartime propagandists in London.

A Christmas 1940 memorandum in the archive of Britain’s Political Warfare Executive cautioned against dropping explosives on the German populace during the holiday season for fear its effects could be the opposite of what was intended.

Written by Richard Crossman, head of the German section of the Ministry of Economic Warfare, it notes that the festive season is a time when German civilians and troops alike “will feel the absence of their families more strongly and will be most susceptible for this reason to certain lines of propaganda, particularly if that propaganda is made to appear as though it were not propaganda at all.”

Addressing the head of the propaganda division of the Special Operations Executive, he said his team had developed a plan combining radio broadcasts with leaflet drops in the hope of “exploiting Christmas Eve in order to demoralise German civilians and the German Armies of Occupation.”

The Air Ministry, however, was refusing to co-operate, insisting that if a raid did take place on Christmas Eve, they would be dropping bombs, not leaflets.

Crossman’s department was concerned.

“Germany, as you know, takes the Christmas festival very seriously indeed, and a bombing raid on that day would probably harden civilian morale against us as well as [give] German propaganda a handle against us in such places as the Vatican.”

As an alternative, Crossman proposed leaflets bearing a message along the lines of: “Peace on earth, but only when Hitler is smashed.”

The RAF was skeptical that such exercises were of any consequence and said as much in its response to Crossman’s proposal: “The Germans have assiduously preached ‘Guns before Butter.’ Is not this more likely to come home to roost if Christmas festivities are interrupted by bombs rather than if a few aircraft drop paper which will not be found until the following day?”

No leaflet drop is believed to have been made and, regardless, the RAF was hamstrung by a two-day Christmas truce in the air war between Britain and Germany.

But the relentless advance of communications technology was already outpacing the ministry’s stuffed shirts and brass hats when it came to psychological warfare.

As the Second World War escalated into a global conflict of unparalleled proportions, pamphlets and leaflets rained down on opposing troops. Eight billion were dropped by Allies in the Mediterranean and European theatres alone.But radio had a more far-reaching effect.

Charles Rolo, a British-born journalist who would go on to become literary editor of The Atlantic, wrote in 1943 that radio “has been streamlined from a crude propaganda bludgeon into the most powerful single instrument of political warfare the world has ever known.”

“More flexible in use and infinitely stronger in emotional impact than the printed word,” he wrote in a treatise entitled Radio War, “as a weapon of war waged psychologically, radio has no equal.”

Radio personalities whose sole purpose was to get into the heads of the enemy rose to prominence between 1939 and 1945.

There was Axis Sally, a former showgirl from Maine whose real name was Mildred Gillars. She became one of the Third Reich’s most prominent radio voices with “Home Sweet Home,” a propaganda show directed at American troops.

Germany started hiring American fascist broadcasters as early as 1939.

After broadcasting patently “fake news” from Berlin for virtually the entire war, Lord Haw Haw—William Joyce, a scarfaced American-born teacher raised in Ireland—was captured and hanged in 1946. At his peak, it is estimated that six million Britons regularly tuned in to his broadcasts, which began with the distinctive “Germany calling, Germany calling” in Joyce’s high-English accent.

Journalist William Shirer called him “the war’s outstanding radio traitor.”

There were others—Germany started hiring American fascist broadcasters as early as 1939—but Nazi propaganda chief Josef Goebbels considered Joyce “the best horse in my stable” and he was rewarded with German citizenship.

Nazi Germany revolutionized the use of radio and film for propaganda. By 1943, the Germans were broadcasting more than 200 international programs in over 30 languages worldwide, in addition to encamped soldiers of all Allied nations.

Propagandist radio in the European theatre was not the sole domain of the Nazis, however.

Starting in 1941, Briton Selfton Delmer—known as “Der Chef”—operated phony German radio stations, including Gustav Siegfried Eins, or GS1, which masqueraded as an actual Nazi radio station broadcasting to fellow Germans at home; Soldatensender Calais, which posed as a German station for troops in France; and Atlantiksender, which spread targeted disinformation to U-boats in the Atlantic.

His programs reported such juicy prospects as injured German soldiers receiving infusions of syphilis-tainted blood from captured Poles and Slavs, and gossiped about an Italian diplomat in Berlin who was bedding the wives of German officers.

In November 1943, Delmer wrote Der Chef out of existence with a script that had Nazi troops storming the studio and “shooting” him mid-broadcast. Beginning in May 1944, he produced a German-language newspaper called Nachrichten für die Truppe (News for the Troops), airdropping it to soldiers on the Western Front.

Goebbels was a master of the art, but even he had to admit a month before he committed suicide that “enemy propaganda is beginning to have an uncomfortably noticeable effect on the German people.

“Anglo-American leaflets are now no longer carelessly thrown aside but are read attentively; British broadcasts have a grateful audience.”

American Iva Toguri was the best-known of at least a dozen “Tokyo Roses” broadcasting in the Pacific. [Wikimedia]

Calling herself “Orphan Ann,” Toguri’s role on her radio show “The Zero Hour” is still disputed (Gerald Ford granted her a presidential pardon in 1977, more than two decades after she had served six years on a treason conviction). It is said in court papers that she made 340 broadcasts between November 1943 and August 1945.

The Japanese propagandist programs were distinguished by their sultry voiced hostesses, including Canadian June Suyama, “The Nightingale of Nanking.” They originated from as many as 13 Japanese-occupied locations around the Pacific.

The Japanese propagandist programs were distinguished by their sultry voiced hostesses.

Toguri’s program featured popular music laced with stories of infidelity and the easy life back home, lighthearted insults directed at her “thankless wretches” and “honourable boneheads,” and ever-present reminders of the mosquito-infested miseries of jungle life.

It was all underscored by unsettlingly accurate references to specific Allied units and their locations, even individuals, along with subtly menacing warnings about what was in store for them—which, disturbingly often, proved true.

But it was music that wielded many of the most damaging blows to homesick and lovelorn soldiers, whether they be in the cold of winter or the blistering heat of tropical islands.

A record jacket for the song “White Christmas” by Bing Crosby, released in 1942. [Wikimedia]

“We laughed. We were only 17; none of us even had steady girlfriends or wives.”

Yet few mediums can stir the emotions like music can, and the propagandist broadcasters knew it well. No matter how dismissive listeners may have been of their wild claims and verbal attempts at undermining morale, they often couldn’t avoid the allure of music and the more insidious effects it had.

Wartime music could exacerbate misery, loneliness and heartache like nothing else—tunes like Marlene Dietrich’s “Lili Marlene,” Vera Lynn’s “(There’ll Be Bluebirds Over) The White Cliffs of Dover” and, during the yuletide season, none more than “White Christmas.”

“Music reaches deep into the mind to create decision-affecting moods,” said Music and Combat Motivation, a 2015 paper produced by graduate students attending the Air Command and Staff College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama.

“With the knowledge of the influence of these factors, many governments intentionally tried to use music to sway enemy soldiers’ morale through propaganda in WW II.”

The paper cited instances in both the U.S. Civil War and the First World War in which music served to undermine troops’ fighting spirit—the Blues and the Greys were known to have “battles of the bands” and joint singalongs which, much to the chagrin of their commanders, served only to pacify soldiers on both sides.

The paper said all the major powers of the Second World War used music in attempts to sabotage enemy morale and erode the will to fight.

An American soldier loads leaflets into a cluster bomb container at a U.S. military printing plant in Japan during the Korean War. The container holds 22,500 leaflets. [Wikimedia]

Christmas longing was notably exploited in a 2010 campaign by the Colombian military to demobilize FARC guerrillas, with whom they had been fighting for decades.

Government soldiers picked nine 25-metre-tall trees adjacent to paths frequented by the guerrillas and decorated them with lights, activated by motion sensor. They hung banners next to them saying: “If Christmas can come to the jungle, you too can come home. Demobilize. At Christmas, everything is possible.”

The campaign, called Operation Christmas (not to be confused with the Hallmark movie of the same name), inspired 331 fighters to leave FARC’s ranks, a 30 per cent increase over the previous year.

“The effectiveness of this campaign wasn’t just a matter of making the target audience feel, but provoking the audience’s current emotional state for the desired outcome,” wrote Alicia Wanless, a researcher at King’s College London.

The military followed up with Operation Rivers of Light, in which civilians close to the conflict areas, as well as friends and relatives of guerrillas, sent Christmas letters in floating LED-illuminated balls via rivers used by the insurgents; 180 left the ranks, including a FARC commander and one of the group’s main bombmakers.

Some psychological warfare efforts were hokey attempts that could easily be sloughed off by their intended targets, said Cook. “But there are deeper seeds of disquiet and disillusionment that emerge over time, especially for people under tremendous stress and strain that we can scarcely imagine.”

Advertisement