Many young volunteers had little idea what they were in for when they enlisted for early service in the First World War.

They anticipated a grand adventure, “a jolly good show” and done. The conventional wisdom was that it would all be over by Christmas 1914. Of course, it wasn’t, and as the months turned into years, the longing and suffering deepened.

The mud got deeper, the rats more populous, the cynicism sharper, the casualty lists longer. Soldiers’ lifelines were the letters and packages to and from home.

Correspondence was the next best thing to being back there: a newsfeed and an outlet (measured, mind you, due to censorship, both officially and self-imposed); reassurance that, whatever madness enveloped you, there was still that familiar place where love and normalcy abounded. The written word, composed or read, was sanctuary.

“If you could only see them when the mail comes in,” Reverend B.W. Pullinger told a congregation in Saskatoon after returning from Flanders, Belgium, in 1917.

“How they crowd round the postman and how they go off into a corner to devour every word in their letters. Not only do they read and re-read every word, but they read the envelope, the address, the postmark, and everything.”

By Christmas 1917, the Canadians had been through the Battle of the Somme, they’d been gassed at Ypres, won great victories at Vimy Ridge, Cambrai and Hill 70, and they’d just come through the epic struggle at Passchendaele. They had seen more than their share of death, and some had even cheated it.

Mail call was never higher on the Canadians’ priority list.

Belfast-born Private John Russell (Jack) Clark, assigned to the 13th Canadian Field Ambulance, appreciated the Christmas parcels he received on Boxing Day from his “Darling Eva.”

Until the mail finally arrived, it hadn’t been much of holiday for the five-foot-seven, 140-pound former store clerk with flat feet.

“I spent a very, very quiet and dull Xmas,” Clark wrote in a letter from “Somewhere in France” on Dec. 27, 1917. “Worse than last year I do believe and that is saying something. Somehow, I did not realize it was Xmas day.

“That night we had a little spread of supplies to celebrate the wonderful day. The menu consisted of…now don’t smile—pork, potatoes and cabbage, plum pudding with sauce, tea and beer.… I was so disgusted and fed up. I just wanted to be back home. I seriously hope it is going to be the last Xmas I spend in France.

“If you could only see them when the mail comes in.”

“And to crown it all, Eva, we were all disappointed about the Canadian Xmas mail, especially as we have been getting no letters. I had a far happier time of it last night because it was then I received your two dandy parcels…I had a happier time unpacking them and we (the boys in my dugout) did enjoy ourselves.…You were the means of cheering some lonely boys at the front.

“My one big wish is that I may be back home to you safe and well before another year comes round.”

It was indeed the last Christmas Clark spent in France. He returned to Canada at war’s end and is believed to have married his darling Eva Auchinachie of Victoria. The couple had two children, Elizabeth and Russell, and eventually moved to Juneau, Alaska. He died in 1974, she in 1977.

Robert Hale emigrated to Canada from his native London as a teenager. Serving with the Canadian Field Artillery, he was shot in the left forearm at Ypres in June 1916. He wrote to his “Dearest Alice” on Dec. 30, 1917, from France.

“It was a great pleasure for me to receive your lovely parcel yesterday,” he said. “The contents were excellent. The cake especially was grand. Did you make it? Thank you very much Alice for that pipe. It was just what I wanted. I think you must be a mind reader. You always send me something I need.

“There was something in your parcel, which was better than all else. Those two kisses for Christmas and New Year’s. I think they are the best present I have ever had, dear. I only wish I could really have them.

“Somehow lately, I have been getting awfully lonely. I don’t know why. I often sit and think of you and I long to be back with you again. It seems so long ago when you and I used to be together. I intend to try and make up for these lost years if I am lucky enough to come home to you again.”

He signed off in awkwardly reserved fashion, “from your old and sincere friend,

Bob.”

Hale, by then a corporal, was wounded again in the left arm, shoulder and both legs by shrapnel in October 1918. He eventually returned to Canada, where he married his sweetheart, Alice, in 1920.

“You were the means of cheering some lonely boys at the front.”

Just 51 per cent of those who enlisted between 1914 and 1918 were born in Canada. The rest were immigrants, primarily from Britain, and it was among them that the compulsion to fight for king and country (the old country) was particularly strong. Many still looked on what was then the Dominion of Canada as a colony.

But after Vimy Ridge, after the Hundred Days and all the battles in between, and after Canadian representatives had put their names to the Armistice agreement alongside those of the principal combatants, Canada emerged a nation in the eyes of most.

Many a transplanted Englishman, Welshman, Scotsman and Irishman who signed up in Canadian cities and towns with their eyes cast eastward left the ranks grateful to return as a Canadian in heart as well as on paper. Likewise, many a boy went off to war and, for better or worse, came back a man, if they came back at all.

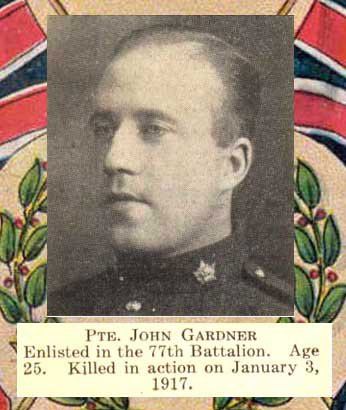

Private John Gardner was born in Belfast on Oct. 5, 1890, and emigrated with his family to Ottawa, where he worked as a plate printer at the American Bank Note Company for eight years before enlisting with the 77th Battalion (Ottawa) on Nov. 16, 1915.

In a letter to his father Samuel on Jan. 2, 1917, Gardner, now with ‘D’ Company, 47th Battalion (British Columbia), said he had seen “all kinds of talk” in the newspapers about peace, “but there is no sign of it as far as I can see.”

He’d been in the trenches for six months.

“I don’t think there can be any agreement until Germany admits herself beaten and agrees to the allies’ terms. War is not so bad as long as the weather keeps dry, but we get our share of rain here in France. But I always try to keep cheerful, for it’s the only way. It does no good grumbling; all you can do is make the best of it.”

He said he got plenty of letters and parcels for Christmas. He especially appreciated the chocolate, saying “chocolate and cake cheer a fellow a whole lot.”

“I hope you had a pleasant time on Christmas Day. By the time next Christmas is here, I hope the war will be over and that I will be back again in Ottawa and home.

“There’s no place like home, dad.”

Gardner was killed the following day, leaving everything he had to his father. He was 26.

James Henderson Fargey, a farmer from Belmont, Man., ended up with the 43rd Battalion (Cameron Highlanders of Canada) after enlisting in Winnipeg at the tender age of 17. Less than 15 months later, in October 1916, he died days after suffering multiple gunshot wounds.On New Year’s Eve 1917, Leslie Duncan Smith, a 20-year-old friend from Belmont with whom he had enlisted, wrote to Fargey’s mother.

“I shall never never forget poor Jim,” said Smith, who’d recovered from a bullet wound to the left thigh received the day before his friend was hit. “He was a good lad with a splendid character and a perfect hero.

“Chocolate and cake cheer a fellow a whole lot.”

“It is hard for us over here where men are killed every day to imagine the pain and distress this war is causing to our dear ones at home. We are so hardened that we think so little of it, but we cannot help it because we would ever be mourning the losses.”

“Remember, Mrs. Fargey,” he added, “that if you want anything done out here for you in the way of looking up friends and or getting information of the whereabouts of anyone I shall do all in my power to find out. I am going to see Jim’s grave the first opportunity I get. There is a special society in France to keep soldiers graves tidy so I have no doubt that the cemetery where Jim’s body is is well kept.”

Smith survived the war and was discharged in Winnipeg on March 24, 1919.

In a poetic letter to his mom Nellie written on Christmas Day 1917, he said he and his fellow soldiers had been spending all their spare time in recent days “getting the dugout fixed up as nicely as possible for Christmas.”

“By Christmas we had it nicely decorated,” he wrote. “Yesterday, Albert Dennis and I went out and gathered some green branches, spruce, fir and cedar also the leaves of some evergreen shrub which I did not recognize but which were very pretty and we easily decorated our home.

“Not having quite enough material, we went out again, and this time we found a real holly tree and with it we were well away. We decorated our mirror with the leaves of the evergreen shrubs, the posts of our supports with cedar and fir and the supports themselves with holly. By the time we had finished, our home looked more like some farmer’s paradise than a bare French cellar a mile and a half from Brother Boche.

“After dinner we sat around the fire and talked—talked of the old days back home before the war, talked of our training days, and talked of the life out here, of our last Christmas also spent on the line and of the events of the intervening year. Presently, someone suggested the question Where will we spend next Christmas?, and in answer to it some of the more optimistic among us said Canada.… A couple of pessimists among us suggested that probably we would still be in France.

“By the time we had finished, our home looked more like some farmer’s paradise.”

“So the day passed and now it is Christmas night. How I would like to be with you all tonight.… I wonder what kind of a night it is at home tonight. We had a light flurry of snow just at dark and now the moon in shining bright and clear upon it from a cloudless sky. Everything is perfectly quiet, it is as though the two opposing forces have agreed to make this day as peaceful as possible and except for an occasional report of a gun one would never know there was a war on. There is just one thing which I would like this evening and as I looked out over the peaceful scene tonight with the glittering white snow sparkling under the moon beams I could not help thinking what a perfect ending a nice sleigh drive would make to this Christmas.

“With a heart full of love to all from your soldier son,

Harold”

Less than 11 months later, on Nov. 11, 1918, a grateful Simpson wrote to his sister Clemmie:

“The glad day has come.… At 9:50 this morning we received the official word that hostilities would cease at 11 a.m. That hour has come and gone. The guns are quiet. The war is over. As yet we can scarcely realize it. It seems we are in a dream from which we are afraid of awakening. War had become for us so real and yet so commonplace that it scarcely seems possible that it can be over.”

Advertisement