Warships of Russia’s Black Sea fleet blockaded Ukrainian ports and shelled cities before Ukrainian missile and drone attacks forced it into a withdrawal.

[Alexander Demianchuk/TASS]

The country of 38 million has no navy to speak of, yet Ukrainian drone and missile strikes have forced its formidable maritime foe into a strategic retreat.

“Most of the combat units, if you take the carriers of cruise missiles, have actually all been relocated, except for one loser who has not yet launched a single missile,” said Captain Dmytro Pletenchuk, apparently referring to the Karakurt-class corvette Tsiklon (Cyclone).

Russia has not commented on the withdrawal.

Formed in 1783, the Black Sea fleet was once considered Russia’s main force in Crimea, but it has almost entirely been chased away and relocated in the months since its deputy commander was killed in action at Mariupol in March 2022 and land-based Ukrainian forces sank the fleet’s flagship three weeks later.

The loss of the Russian cruiser Moskva to Ukrainian Neptune missiles was only the second time a cruiser-class ship was destroyed in combat. The Argentine ARA General Belgrano was sunk by a British submarine during the 1982 Falklands War.

Moskva’s sinking was a major blow to Russian prestige and a symbolic, as well as practical, victory for Kyiv. It was the only ship in the fleet equipped with anti-aircraft missile systems capable of defending an entire naval formation from air attack. Its loss rendered the fleet incapable of operating freely in the northwestern part of the Black Sea, and plans for an amphibious landing near Odesa were abandoned.

Russian naval prospects only deteriorated from there.

The Black Sea fleet is depicted by 19th century Russian artist Nikolay Pavlovich Krasovsky after the 1853 Battle of Synope. The fleet was established in 1783.

[Nikolay Pavlovich Krasovsky/Wikimedia]

A July 31, 2022, drone strike at the fleet headquarters in Sevastopol wounded several people and forced the cancellation of Navy Day commemorations. Nine days later, Western officials confirmed that strikes at Crimea’s Saky airbase took out more than half the fleet’s combat jets. Saky has been hit twice more since.

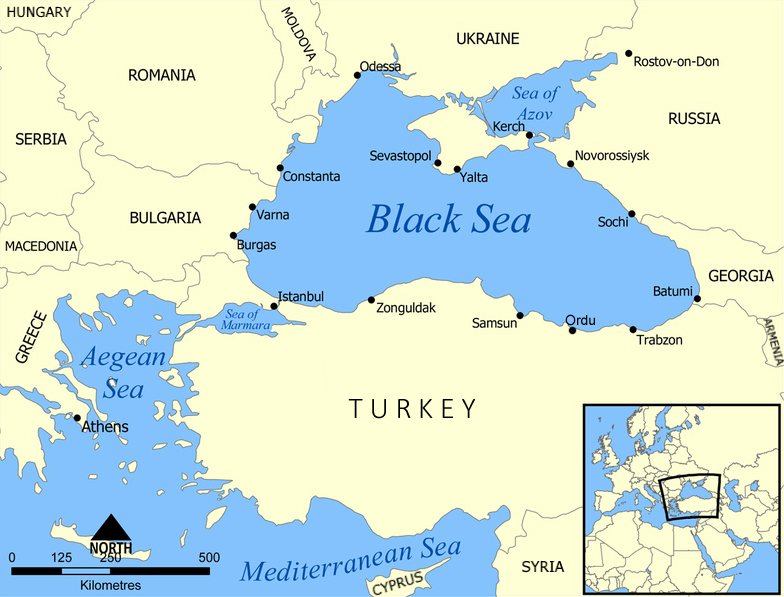

Access to the inland Black Sea is controlled by Turkey. It is invaluable to the trade prospects of several countries.

[Wikimedia]

Yet Ukraine has continued to hit Russian assets as recently as March 23, 2024, when Ukraine-built Neptunes damaged several Russian vessels, including an intelligence ship, and destroyed a Sevastopol oil depot, port facilities and the amphibious landing ship Kostiantyn Olshansky at dockside. The ship was part of the Ukrainian navy before Russia captured it when it annexed the Black Sea peninsula in 2014.

Two days after the Sevastopol attack, U.K. defence minister Grant Shapps described Russia’s Black Sea fleet as “functionally inactive.”

Experts chalk up Ukrainian success to technological innovation, audacity and Russian incompetence. Besides missiles and airborne drones, Ukraine has employed remote-controlled drone boats laden with explosives, similar to ones used by Houthi rebels in the Red Sea off Yemen.

They have “allowed Ukraine to tip the scales of naval warfare in its favor despite Russia’s massive superiority in firepower,” The Associated Press reported on March 5.

The great emblem of Russia’s Black Sea fleet. Its losses and subsequent withdrawal during the current Ukraine war are major blows to Russian prestige.

[Wikimedia]

Ukraine has also relied on cruise missiles provided by Britain and France for striking Russian assets in Crimea. They are launched from Ukraine’s Soviet-era warplanes and have a range of more than 250 kilometres.

“Western officials praise the efficiency of the Ukrainian attacks, noting that Kyiv has smartly used its limited resources to defeat far stronger Russian forces…effectively blunting Moscow’s naval dominance,” AP reported.

“Besides being militarily (and financially) overstretched, Russia cannot deploy any new battleships in the area.”

Alper Coşkun, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, D.C., wrote in February that Russia’s inability to prevent these developments in the Black Sea has “tarnished its swagger.” And worse.

The losses, he said in an essay for the journal of the Liechtenstein thinktank GIS, amount to “an actual degradation of Russian naval capabilities” in the region.

“This problem is compounded by the fact that, for now, it is next to impossible to replace these assets,” Coşkun said. “Besides being militarily (and financially) overstretched, Russia cannot deploy any new battleships in the area.”

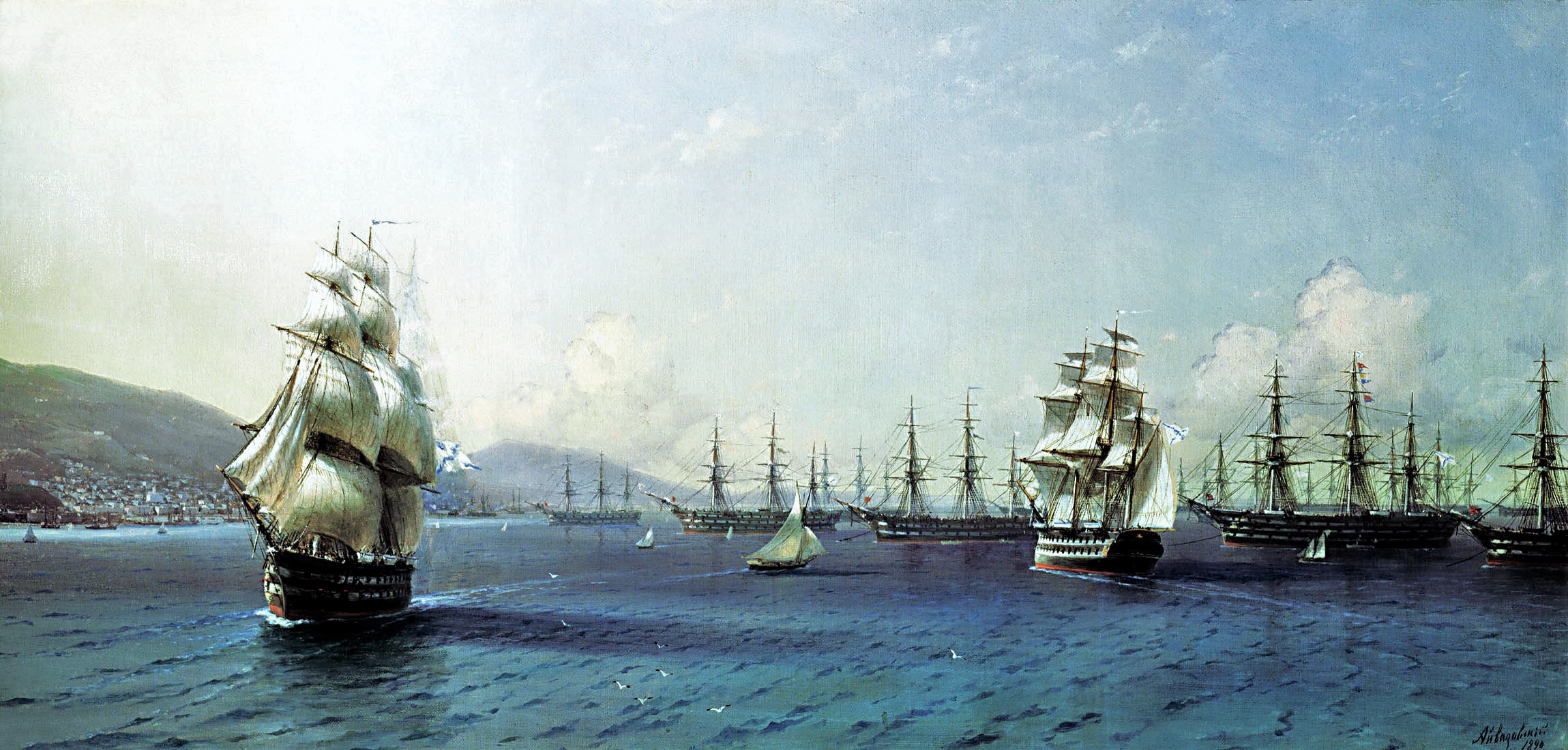

The Black Sea fleet in the Bay of Theodosia, Crimea, just before the Crimean War, painted in 1890 by Armenian artist Ivan Aivazovsky.

[Ivan Aivazovsky/Wikimedia]

The move has helped Kyiv both militarily and economically. With the collapse of Russian blockades of Ukrainian export routes, goods such as the country’s vital grain commodity are able to ship out by sea.

But the situation also stands to enhance Turkey’s influence in the area. It is the gatekeeper of the Black Sea where, Coşkun notes, Istanbul has stepped up natural gas extraction and maintains energy pipelines.

“As the war drags on and Ukraine sustains its offensive operations in the Black Sea, which they brazenly vow to do, Russia’s naval supremacy will erode,” he predicts. “This, in turn, will shift the balance of power in the regional maritime domain in Turkey’s favor as it comfortably watches these developments from the sidelines.”

Coşkun called it a “risky forecast that is bound to preoccupy Russia,” the country NATO’s 2023 Vilnius Summit dubbed “the most significant and direct threat to Allies’ security and peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area.”

Advertisement