German survivors from U-210 are taken prisoner aboard HMCS Assiniboine, the ship that sank their U-boat during a furious surface battle on Aug. 6, 1942. They were taken to Halifax and then on to the United States, where they were interrogated. [DND/PA-116282]

Leutnant zur See Günther Göhlich was just 22 years old but despite his youth—perhaps because of it—he was, according to his Canadian and American interrogators, “arrogant and conceited.” He was the boat’s executive officer.

“He had all the makings of a youthful martinet and was most un-popular on board,” said an October 1942 report by the U.S. Navy. “It was stated that he lost his head during the sinking and that an engine-room petty officer stood behind him with a heavy wrench, intent on murdering him as soon as the lights failed.

“The fact that the lights remained on appears to have saved his life.”

Göhlich is part of an intimate and colourful profile of a U-boat crew compiled from interrogations of 16 survivors conducted in the United States and 21 more who had been taken to England. The secret naval intelligence report was filed Oct. 25, 1942, two and a half months after U-210 was rammed and sunk by Assiniboine.

HMCS Assiniboine, the Canadian destroyer that sank U-210 in the North Atlantic south-southeast of Cape Farewell, Greenland. Assiniboine was damaged and set afire during a battle after depth charges had forced the U-boat to the surface. [DND/PA-135967]

One 19-year-old was the son of an alpine guide who had left his father’s home in Austria the previous winter to join the Kriegsmarine. He used the traditional Austrian hello “Grüss Gott!” (greet God) with his interrogators and still assessed the wealth of his neighbours in terms of the number of cows they possessed.

Another junior seaman, age 18, said he had practically been pressed into service at the last moment to make up a full complement, which even then was one or two men short. He had received six-months’ basic training and had never before been on any sort of ship.

The oldest crew member, age 38, was a civilian diver and veteran merchant mariner who claimed that he had been drafted as an able seaman by mistake.

“He was extremely bitter about this error and stated that he had had no intention of going to sea at all, much less in a U-boat. He said that while in dock he had instructed in seamanship 10 of the more youthful enlisted men, whose previous occupations included those of confectioner, farm hand, baker, and saddler.”

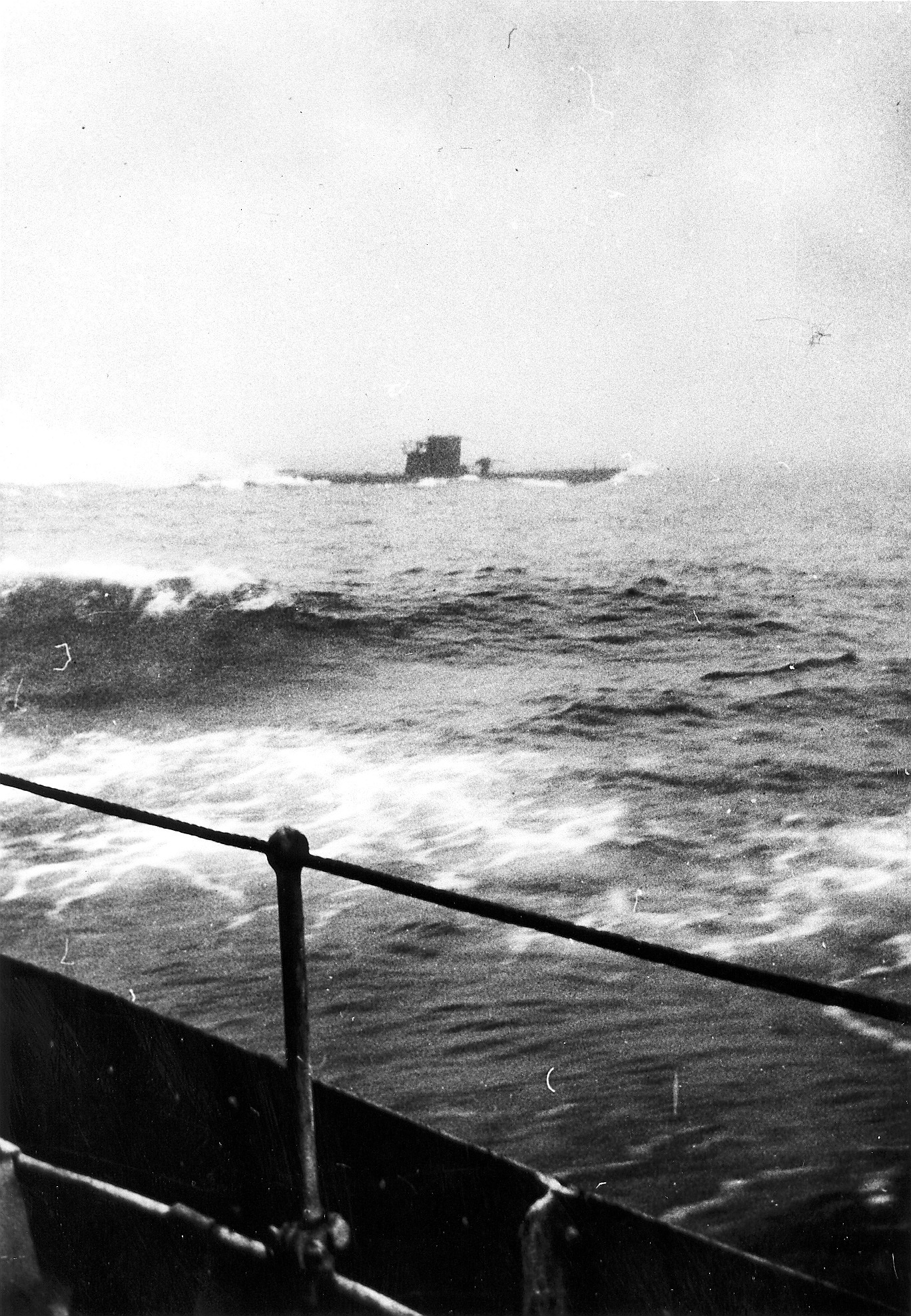

German submarine U-210 maneuvering at full speed on the surface in a desperate and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to evade destruction by HMCS Assiniboine. [DND/PA-037443]

“There is every indication from prisoners’ remarks,” the report said, “that the standard of foods carried on board remains relatively high.”

The crew’s physical condition varied, from “marked debility to robust.”

But Göhlich appeared to be the real peach of the batch.

After his captain was killed in action and his boat sunk, the executive officer shouted “hysterically” for help as he swam the frigid waters south-southeast of Cape Farewell, Greenland. A petty officer disdainfully told him to shut up.

“Göhlich was of the 1938 Naval Term (graduating class),” said the report. “His interrogators regarded him as one of the worse [sic] types of prisoner.”

One other officer survived the sinking. The engineer officer, Leutnant (Ing.) Heinz Sorber, also 22, was “a more decent type and, apparently, a capable officer.”

“Though previously a Party member, he told and enjoyed anti-Nazi jokes,” said the report. Sorber served aboard the German battleship Scharnhorst for more than a year and had survived the sinking of U-580 after it was rammed in the Baltic.

“Sorber was pleasant and good-natured, but thoroughly security-minded,” wrote his interrogators. “He was prematurely bald, having lost all his hair suddenly, he said, during his period of basic training.”

HMCS Assiniboine rams U-210 after the destroyer’s 4.7-inch gun hit the U-boat’s conning tower. Six of the U-boat crew-two officers and four enlisted crew-were killed during the action; 37 survived. [DND/PA-037445]

Prisoners said Lemcke had been removed from his destroyer in 1940 and put in charge of an anti-aircraft battery. He was busted down to the rank of seaman and sentenced to three months in a penal battalion, all for exercising disciplinary brutality and failing to comply with naval regulations.

“He had caused a member of a gun crew to be beaten in front of the entire division for falling asleep on duty, as he realized the man was very young and might be shot if subjected to court-martial. He had, therefore, taken matters into his own hands.”

He served a three-month probation aboard a minesweeper and was promoted to leutnant zur see, a junior rank equivalent to sub-lieutenant or ensign. After a cruise with an experienced U-boat commander, he assumed command of U-210 with the rank of oberleutnant.

He was reinstated in his former rank of kapitänleutnant when he left Kiel for his first war cruise. The report said Lemcke, whose awards included an Iron Cross, told his story openly to suppress rumours.

“While he was admired for his frankness, it is not believed that he was highly regarded otherwise by his crew. The story was told that he drank champagne and brandy on board, and that he ordered the boat submerged on rough nights as the motion on the surface prevented him from sleeping.”

Several prisoners appeared to consider Lemcke an inexperienced commander and blamed him for the loss of his boat. Specifically, some said he overestimated the damage he had caused Assiniboine during their exchange of fire and should have dived.

Lemcke had married Luise Moelck of Kiel, Germany, in June 1941. He received a radio message announcing his wife had given birth to twins, a boy and a girl—the crew each received two bottles of beer in celebration—about eight days before he was “blown to bits” by a direct hit on U-210’s conning tower from Assiniboine’s 4.7-inch gun. Four enlisted men were also killed in the battle.

The report said the crew’s inexperience led to a number of mishaps.

On one occasion, the captain forgot to take into account the air pressure in the boat and flung open the conning tower hatch when they surfaced. He was hurled onto the bridge, injuring his face.

Another time, the diesel engines were started before the main induction valve was opened, causing the eyes of the engine-room crew to “protrude violently.” Three men managed to open the intake just in time to avert a serious accident.

During trials, the executive officer took photographs of the ship’s company lined up on deck. A seaman sent one of the photographs home. A flotilla order arrived days later ordering the man punished for what was considered a security breach.

A ship’s boat rescues survivors from U-210 (wearing life-jackets) after the U-boat sank in the North Atlantic. The ‘X’ above one of the survivors indicates a German submariner who had lived in Saskatchewan for 17 years. He is not mentioned in the U.S. intelligence report. [CWM 19880063-001_7]

One prisoner estimated that at least one U-boat was going down each week, and that at least 100 had been lost in all (87 were sunk in 1942 alone). None seemed particularly surprised that five were believed lost from their own wolf pack.

“Though it is true that many men still volunteer genuinely for the U-boat service, there is much evidence of compulsion,” said the report. “One man said that at a transit base volunteers for U-boat service were called for from a group of 80 men.

“Thirty-five stepped forward, but it was necessary to order all except a handful to do likewise until the required number was reached.”

There was no evidence at the time that volunteers were being sought from the Wehrmacht, but survivors said there were ex-Luftwaffe men in the U-boat service who “bitterly regret having made the change.” Others volunteered for the U-boat arm rather than submit to compulsory service on the Russian front.

Contraction of venereal disease in the Kriegsmarine, once punishable by three-days’ detention, was considered “cowardice before the enemy” and subject to court martial by the time U-210 went down.

“The result is that few men come forward to confess the truth and the number of sufferers from this complaint in the U-boat service has risen correspondingly,” said the report. “This has been confirmed by medical officers examining prisoners of war on arrival in the United Kingdom.

“The reason for making venereal disease a court-martial offense is said by prisoners to be the ease with which those who did not wish to sail could contract it in French ports.”

The report said there was every reason to believe that U-210’s crew generally based their beliefs and hopes on Nazi propaganda. Several thought England would be crushed before 1943 was out, and that Germany and the United States would then come to terms, “particularly as America would sue for peace as soon as she learned that she was ‘fighting only for the Jews.’”

“The same prisoners claimed that all Germans knew of the discovery in some French archives of a secret document drawn up by Jews calling for sterilization of all Germans in the event of an Allied victory. They seemed personally frightened of the consequences of Germany losing the war.”

In fact, Theodore Newman Kaufman, an American Jew from New York, had self-published the 104-page book Germany Must Perish! in 1941. It advocated sterilization of all Germans and the territorial dismemberment of Germany, arguing it would achieve world peace. The Nazi Party used the book to support its case that Jews were plotting against Germany.

“No man has ever done so irresponsible a disservice to the cause his nation is fighting and suffering for than…Nathan Kaufman,” journalist Howard K. Smith wrote after the book became known while he was visiting Germany. “His half-baked brochure provided the Nazis with one of the best light artillery pieces they have.”

U-210’s crew mocked the Allied bombing of German cities, decrying the bombers’ “poor aim” and telling their captors that movies of the German bombing of London were widely shown as visual proof of retaliation for English bombing of Germany.

The report doesn’t say where the prisoners were interrogated, but U-boat crews and other PoWs were typically landed in New England and then taken to Fort Hunt, Virginia, an army-navy interrogation center outside Washington, D.C. Once interrogations were completed, they were transferred to a prisoner-of-war camp.

Some 425,000 German PoWs were held in 700 camps throughout the United States during the war; another 34,000-plus were in 40 camps in Canada.

While the fate of most of U-210’s crew is unknown, many would have been returned to a partitioned Germany after the war, although many PoWs returned to settle in North America over the years.

Günther Göhlich was one of them. He became a veterinarian and died in Toronto in 2014, age 95. His obituary said he would be remembered for his love of animals, nature and sailing, which it said he developed in the Kriegsmarine.

He was apparently a good card and chess player, skills “he perfected during his time when he was held captive by the Yankees as a PoW.”

The obituary said he would also be remembered for “his kindness and generosity, sense of fairness, his honesty, his directness and for holding his own point of view on any subject he held close to his heart.”

Advertisement