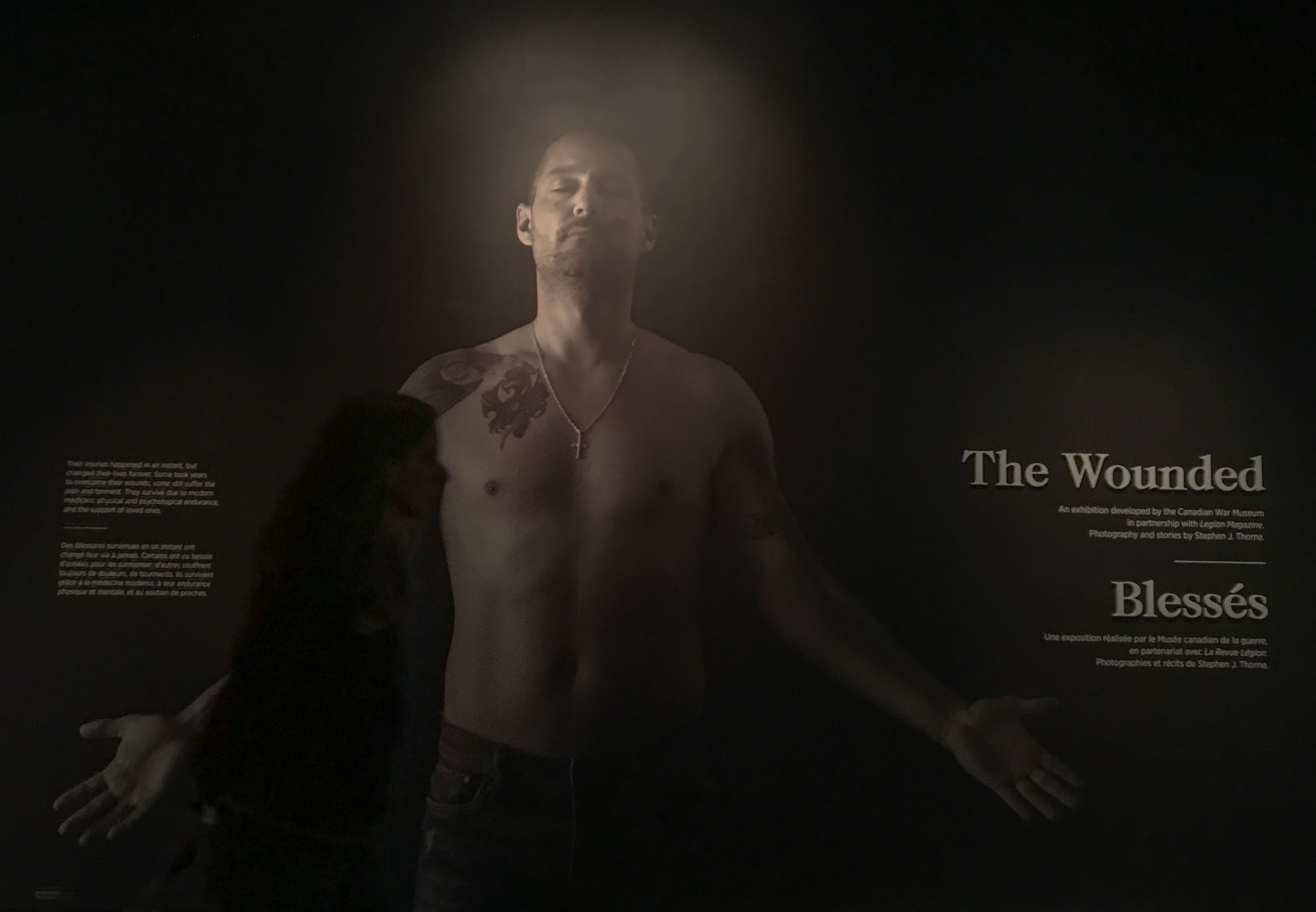

The Wounded exhibition at the Canadian War Museum continues to June 2. [Stephen J. Thorne]

There is an adage that is embraced by all the military, but especially the infantry: I’ve got your back.

It’s fundamental to any successful endeavour against an enemy in battle. But who’s got your back when the battlefield is life and the enemy is yourself?

“I think it’s even more significant now than when I was in the military,” says Helene LeScelleur, a former captain in 5 Field Ambulance who lost her military career to post-traumatic stress disorder.

“The military community is very strong; the brotherhood is very strong. But the brotherhood within the wounded community is even stronger.”

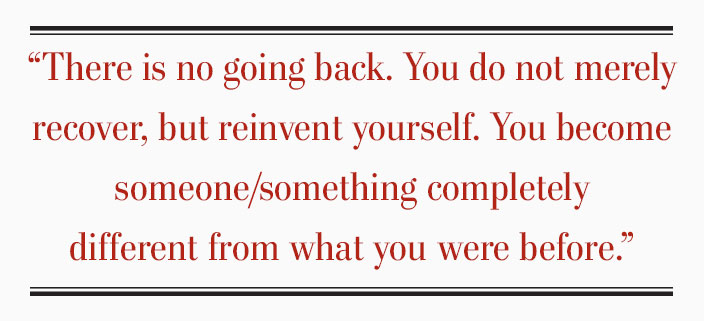

Macha Khoudja-Poirier alongside her portrait at The Wounded exhibition in the Canadian War Museum. The former medic battled PTSD for 10 years before seeking help. [CANADIAN WAR MUSEUM]

Vandoos Gorden Boivin and Andre Girard were inseparable during the Invictus Games in Toronto in 2017, like a couple of wide-eyed, star-struck kids as they cruised the events and took in the elaborate opening and closing ceremonies.

Boiven nearly lost his left arm after a rocket-propelled grenade stripped it of flesh from shoulder to wrist; Girard became known as the Miracle Man after he survived a bullet to the head. The psychological wounds went deeper.

“It was tough to say ‘I need help. I am broken,’” Boivin said of life after his physical self was patched back together. “That part is difficult to do but, once you do it, they were there for me.”

Wounded Vandoos Gorden Boivin and Andre Girard were inseparable during the Invictus Games in Toronto in 2017. [Stephen J. Thorne]

The extent of Knisley’s amputation—his right leg all the way to his pelvis—became a point of pride about which he never failed to remind the others. More than brothers in arms, they became brothers in arms, legs, body and mind.

Wounded warrior Gorden Boiven (LEFT) hams it up with an old buddy from Quebec City, Frédéric Poitras. Boiven’s portrait became the signature image of the exhibition. [CANADIAN WAR MUSEUM]

Said Trauner: “We’d boost each other’s morale and bust each other’s balls.”

Stephen Thorne with Leah Cuffe and Mike Trauner. [Canadian War Museum]

One of the wounded, a sailor, came to me several times expressing guilt that his experience—a disabling fall aboard ship and subsequent struggles to work his way through his injuries—wasn’t worthy to have his picture stand next to the others.

But despite his own sufferings, that swabby, Joe Kiraly, is an inspiration to and pillar of the wounded community. He helped his own ascent from the depths of darkness by helping others, and continues to do so.

“Thanks for everything you have done for me personally and for all those you have helped,” was typical of the messages he received upon his recent retirement.

Martin Renaud and his father André were deployed in Afghanistan at the same time in 2007. André was 15 kilometres from the explosion that robbed his son of his legs; he heard the blast and felt the shockwave. [CANADIAN WAR MUSEUM]

“We have learned to speak about the real things,” she said. “You’re talking from your soul. You’re not talking from someone who’s trying to hide everything behind a bottle or because you think you’re too strong for that.

Andrew Knisley and his father Ken with Stephen Thorne at the Canadian War Museum exhibition of The Wounded. [Stephen J. Thorne]

That healing, or “recovery,” is a process, not a destination. The wounded learn to live with what they have been left.

“When people say ‘recovery,’ you typically think of returning to how you were before your illness or injury,” said Mike Trauner’s wife, Leah Cuffe. “But there is no going back. You do not merely recover, but reinvent yourself. You become someone/something completely different from what you were before.”

All found support and encouragement in family, the unsung heroes behind the heroic. Cuffe and Tracy Kerr, to name two, supported and took up the causes of their wounded warriors with love, resilience and undying devotion.

Chris Klodt’s wife Deena used tough love to motivate her husband. She was seven months pregnant when Klodt was rendered a quadriplegic by an AK-47 round to the neck during a firefight west of Kandahar.

Natacha Dupuis (LEFT) with partner Daniela Gasca at the Feb. 14 opening of The Wounded at the Canadian War Museum. [CANADIAN WAR MUSEUM]

A year later, with her maternity leave used up, Deena announced she was taking their newborn son Jonthan back to Manitoba, where a job was waiting for her. “If you get your independence back, I will move back,” she promised.

“It was the best thing she ever did for me,” said Klodt, who doubled down and worked like never before.

He was fighting for his independence, knowing that in the end it would bring him the life he wanted, with the woman he loved and the family they had started. Six months later, he was able to dress, feed and bathe himself.

Finally, he phoned Deena and, a month later, she and Jonthan were back. Today, the husband and father of two radiates love for his family and an awe-inspiring joie de vivre.

Justin Brunelle with wife Yara Saikaly and three-month-old Owen. “It comes with the territory and I think I was ready for that,” he said of his ordeal. “It could always have been worse.” [CANADIAN WAR MUSEUM]

With help from rehab, counselling and his wife of 29 years, Donna, he gained perspective and found new purpose as a ministerial adviser and veterans’ rights advocate. He decided that he was the author of his own book and what he did with his life would be what he chose to do with it, whatever the obstacles.

“There was no going back,” he said. “And there’s no point in lamenting that fact. What’s done is done.”

The last interview I did for this series was with Macha Khoudja-Poirier, a medic who had lived with PTSD for 10 years before she sought a diagnosis and treatment, pretty much as I had after more than a decade covering disasters and war.

She imparted a strong message that resonated: wounded veterans have to take responsibility for their own welfare. No one can “take you by the hand and bring you to the clinic,” she said. “If you don’t ask for help, nobody will come.”

It’s a truism that especially applies to those with psychological injury. And that includes most, if not all, of the brotherhood since, for the physically wounded, returning to daily life is only the end of the beginning. They’ve survived; now they must live.

People of all ages have been visiting the Canadian War Museum to experience The Wounded exhibition. The 18 portraits and stories are on until June 2. The exhibition is slated to tour for three years. [Stephen J. Thorne]

For that reason, and for myriad other reasons, the wounded will always walk a road apart.

The Wounded exhibition at the Canadian War Museum continues to June 2. The exhibition is slated to tour for three years. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Advertisement