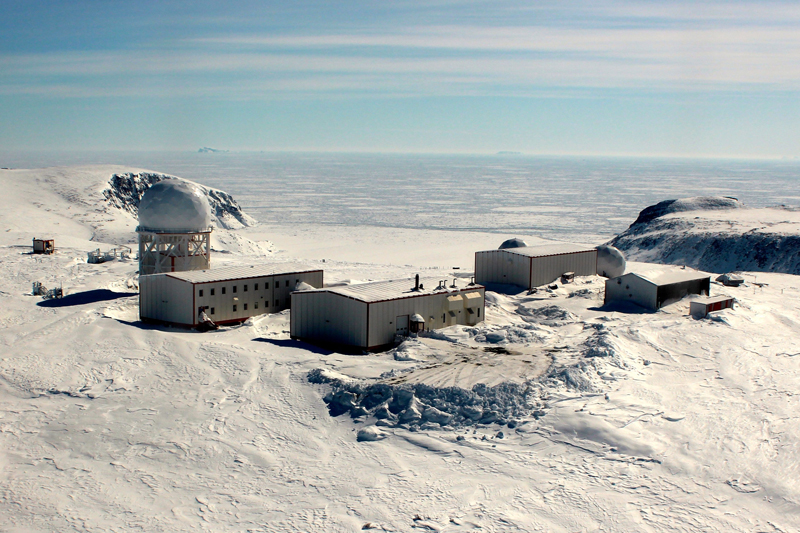

North Warning System site BAF-3 is located in Brevoort Island, Nunavut. This long-range radar site was established in October 1988. [Lianne Girard]

The $592-million contract for the operation and upkeep of the North Warning System (NWS) went to Nasittuq Corp. The Iqaluit-based company takes over from Raytheon Technologies at a particularly sensitive time for Arctic sovereignty and management.

“The Inuit are the eyes of Canada in the Arctic.”

“One of the strongest arguments to demonstrate that the Arctic is within Canadian jurisdiction is the fact that you have people living there and those people are the Inuit,” Clint Davis, the Inuk CEO of Nunasi Corp., a Nasittuq shareholder, told Legion Magazine.

“The Inuit are the eyes of Canada in the Arctic. And we’ve been living there for thousands of years. I think it’s rather appropriate that you actually have the people who’ve lived there the longest actively involved in operating, maintaining and managing these systems that are there to provide defence for North America.”

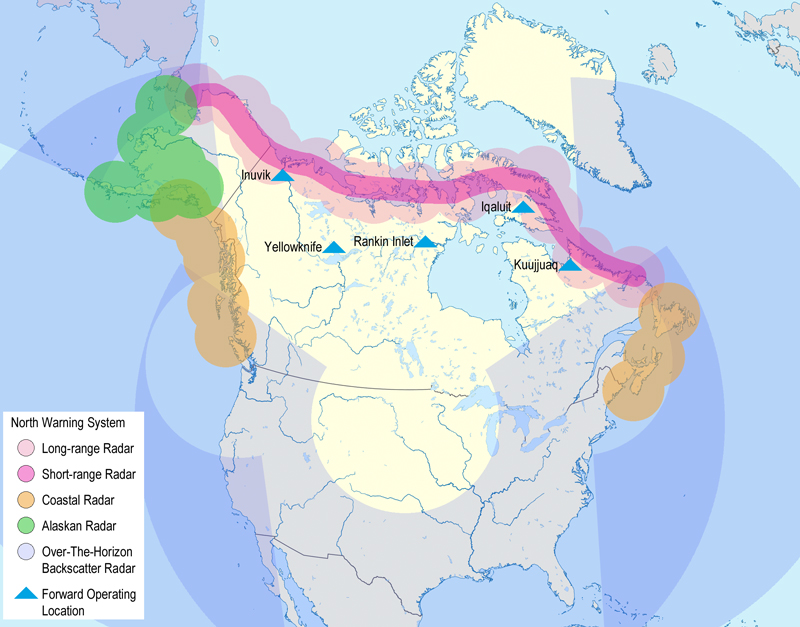

The 37-year-old NWS is a network of dozens of remotely operated radar stations strung 5,000 kilometres along the rim of the Arctic Ocean from Baffin Island and along the Bering Sea to southwestern Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. Effective April 1, Nasittuq will be responsible for 47 of the stations in Canada.

They are the eyes and ears of the continent’s northern gateway, and the Russian military is regularly testing their effectiveness and the Canada-U.S. response in the airspace just beyond both countries’ borders. Moscow often dispatches Cold War-era bombers over the pole to the edge of Canadian and U.S. airspace, where North American Aerospace Defense Command (Norad) aircraft inevitably turn them back.

The North Warning System is a series of long- and short-range radar stations in the Arctic that replaced the Distant Early Warning Line system in the late 1980s. [Challenge and Commitment: A Defence Policy for Canada/Ministry of Defence]

These shifts under the hawkish, even hostile, regime of Russian President Vladimir Putin come as the warming effects of climate change shrink the Arctic ice season and render Arctic waters more navigable. Russian and American vessels appear to have the run of Arctic waters, periodically passing through the fabled Northwest Passage without seeking permission from Ottawa.

The vast Canadian Arctic spans three territories, extends to the North Pole, and encompasses 75 per cent of the country’s coastlines and 40 per cent of its land mass.

“I think more countries are going to start getting bolder about Canada’s North.”

“The sheer expanse of Canada’s North, coupled with its ice-filled seas, harsh climate and more than 36,000 islands makes for a challenging region to monitor—particularly as the North encompasses a significant portion of the air and maritime approaches to North America,” says a federal defence policy released in June 2017.

Eight nations—Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States—have mounted overlapping and disputed Arctic sovereignty claims.

“I think more countries are going to start getting bolder about Canada’s North,” said Davis, originally from northern Labrador. “As the Northwest Passage opens up, I think you’re going to see more traffic going through there and that traffic won’t be monitored.“I think that does raise concerns about sovereignty and security.”

Meanwhile, plans to upgrade the NWS have been bouncing around for years.

U.S. Air Force Lieutenant-General S. Clinton Hinote, deputy chief of staff for strategy, integration and requirements, said in July 2021 that the U.S. and Canada have delayed NWS modernization “for too long.”

Tom Lawson, who served as Canada’s defence chief under former prime minister Stephen Harper, told Eye on the Arctic in December 2020 that hypersonic missiles like those developed by Russia have removed the element of distance—and decision time.

“Russia can employ these missiles from Arctic bases to rapidly target northern sites in North America, and there would be little time to react,” said Lawson, who also served as the deputy commander of Norad.

In August 2021, U.S. Air Force General Glen VanHerck, commander of U.S. Northern Command and Norad, said the NWS was designed to detect “bombers flying at 36,000 feet that had to fly over the homeland to drop a gravity weapon.”

“Ideally, we would like to go to an advanced system—over-the-horizon radar,” VanHerck said during a discussion at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

The North Warning System is a joint United States and Canadian radar system that includes 47 radar sites spanning the Canadian Arctic. [Wikimedia]

“There’s proven technology today that would give us domain awareness. I think it’s crucial, as we create new systems, that we don’t make them singularly focused. Any new systems that we create must be able to not only detect bombers, but cruise missiles and even small [unmanned drones], to be affordable and usable.”

It’s the second time Nasittuq has done the NWS job, which includes flights into some of the country’s most remote locations to service equipment. It last did so between 2001 and 2014. In January 2021, the firm re-organized its corporate structure and became an officially recognized Inuit-controlled company.

“Inuit are First Canadians and Canadians first.”

The new Nasittuq contract includes four two-year option periods for a potential total estimated value of $1.3 billion.

The Arctic is fundamental to the Canadian soul and spirit.

But Davis, an honorary lieutenant-colonel to the Queen’s York Rangers, a primary reserve unit based in Toronto, says population growth and urbanization, mainly along that 300-kilometre-wide belt bordering the United States where most Canadians live, is leaving more and more people disconnected from the North.

The NWS is essential to the air defence of Canada and the United States. [Master Warrant Officer Paul Belanger]

But many, he adds, are “frustrated” with a host of issues largely centred around support and development, and “the lack of collaborative vision” for the North.

“I do hope that certain leaders [make] a real concerted investment in the Arctic. When you look at basic infrastructure, it doesn’t exist compared to other parts of the country. It’s time to change that.”

Advertisement