Then-Captain Alex Watson (left) and village elders converse through a translator during a meeting near Kandahar in 2002. [Stephen J. Thorne]

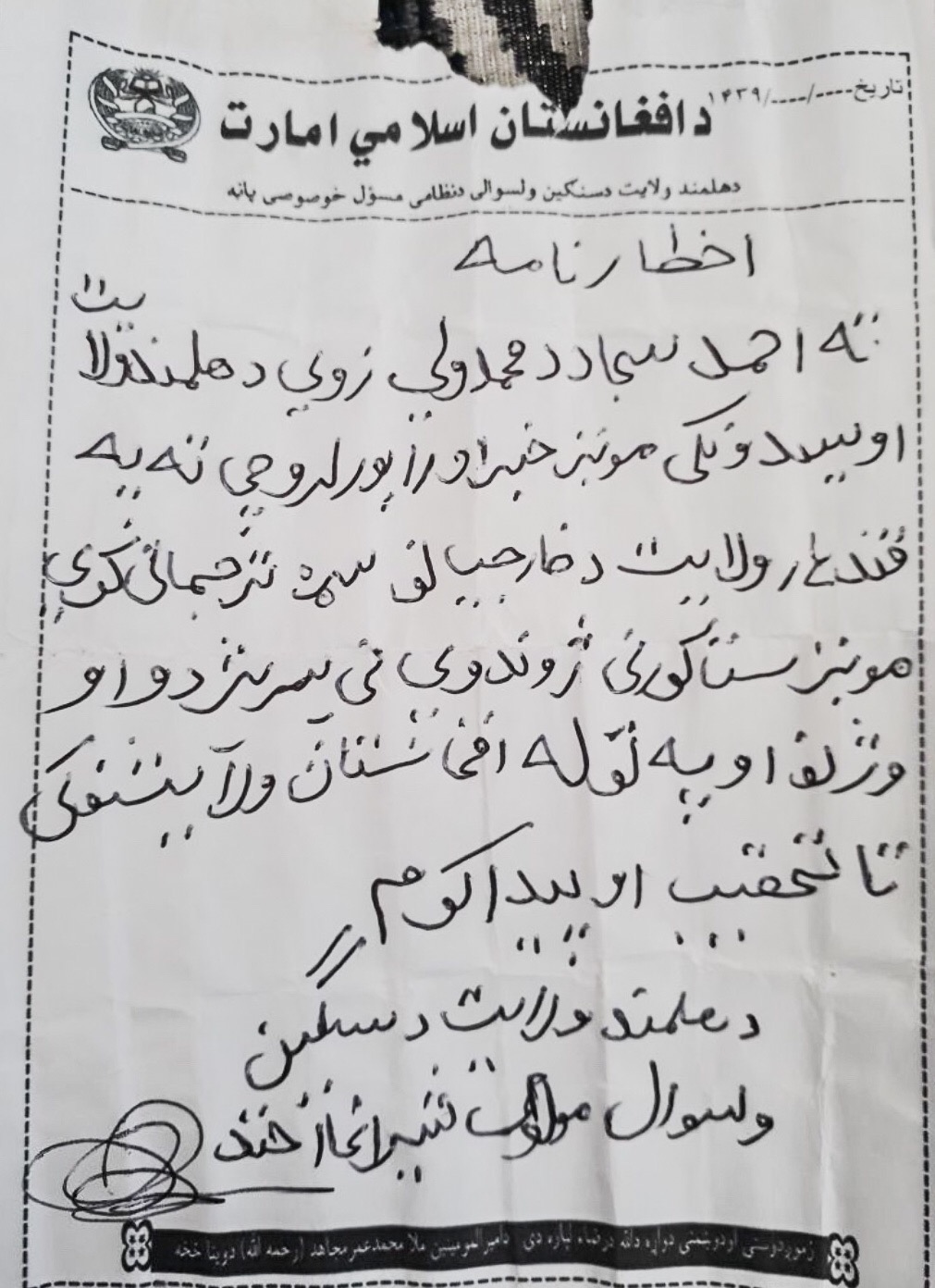

The night letters started arriving at his parents’ home in Afghanistan’s Helmand province soon after Ahmad Sajad Kazimi took a job translating for Canadian and other NATO forces fighting the war on terror.

“Tell your son to quit his job and stop working for coalition forces,” one said. “Otherwise we kill your son because he is co-operating with the Infidels!”

“You AHMAD SAJAD, son of Mohammad Wali, resident of Helmand province,” began another, “we found out that you are working as a linguist with Foreigners in KANDAHAR province. We won’t hesitate in killing your family.

“We are looking [for] you in all other provinces of Afghanistan.”

It was signed Mawlawi Shir Agha Akhond, (Taliban) governor of Sangin district, Helmand, Afghanistan.

They were not idle threats. Kazimi, better known to the troops he worked with by his nickname Alex, knows of several coalition interpreters killed from the time he started translating in June 2009. He moved his family out of Helmand.

“The Taliban and ISIS are worse than wild animals,” he said in an interview with Legion Magazine from Afghanistan, where he was hiding with his pregnant wife while trying to gain entry into Canada.

“They don’t finish an interpreter’s life with just a single bullet. They torture interpreters to death. They only use bullets when they come after their targets into the restricted areas like cities with high security.”

One translator was beheaded, his severed head left on his chest on the Kandahar-Kabul highway. Another was simply shot. A picture of him lying in peaceful repose with a single bullet hole beneath his chin appears on a Facebook page.

“If he has given his life on way of allah, he would have been rewarded with janah (heaven),” wrote one commenter called Muslim Pardes, “but unfortunatly he give his life for bush and obama, who are here to kill some afghans muslims. So who would care about this bastard. may allah bless him with hell and give his family and relatives the hardest life on both worlds.”

Then-Captain Alex Watson (left) with a translator and fellow Canadian troops in a village near Kandahar in 2002. [Stephen J. Thorne]

Kazimi is among about three dozen believed to have slipped through the cracks. Conservative foreign affairs critic Erin O’Toole has said he knows of about 10 with certificates proving their service and whose general whereabouts are known.

“I remember asking my guys, like, ‘who else do we want to bring over,’” said Alex Watson, who as a major commanded a company of Canadian troops employing Kazimi’s services while mentoring an Afghan combat battalion in 2009.

It was Watson’s third tour, and he got all three of his personal interpreters into Canada or the United States. His troops had a stable of about two dozen others who rotated in and out. Kazimi also worked for Australians, Poles and Americans.

“No names came up,” continued Watson, who hired Canada’s first Afghan translators back in 2002, “and then six, seven years later I hear about Alex.”

Kazimi’s cousin translated for U.S. forces and moved to Texas with his family under a special immigration visa. Another cousin worked for British forces and moved to Manchester, where he lives with his wife thanks to a special U.K. visa program.

Kazimi, who passed six intelligence reviews, says he missed out because nobody informed him about the Canadian program.

“This kid Alex was a cut above the rest,” Watson said. “I do remember him. Some of my guys stay in touch with him. It was a case where the troops wanted to get him out but that was never communicated up to me.”

Watson, now a civilian prosecutor, has taken up Kazimi’s case with Ottawa. Except for one sponsored by former cabinet minister John McCallum in 2016, no Afghan interpreter has entered Canada since the program was shut down.

Red T, a New York-based organization representing linguists worldwide, has gone to bat for coalition translators left behind in Afghanistan. Group president Maya Hess wrote Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen in June requesting a meeting.

It was the second time in two years she’s appealed to the Canadian government, without satisfaction.

“To escape persecution by insurgents, many of these linguists have been forced into hiding in their home country or escaped only to be stranded in Europe,” she wrote.

She pointed to Canada’s current policy directing those left behind to go through existing immigration channels, saying the process “represents an extreme hardship for them due to the perils of openly traveling in Afghanistan; the difficulties of applying while homeless or in a refugee camp in Europe; the challenge of the application process itself, including proof of persecution, which is often impossible to procure; an acute lack of resources; and myriad other obstacles.”

Other coalition countries, Britain and the United States among them, have re-evaluated and revised their resettlement policies, granting asylum to linguists who missed the first wave. “Trusting in Canada’s fundamental humanity, we are optimistic that a solution can be found,” wrote Hess.

The minister did not reply.

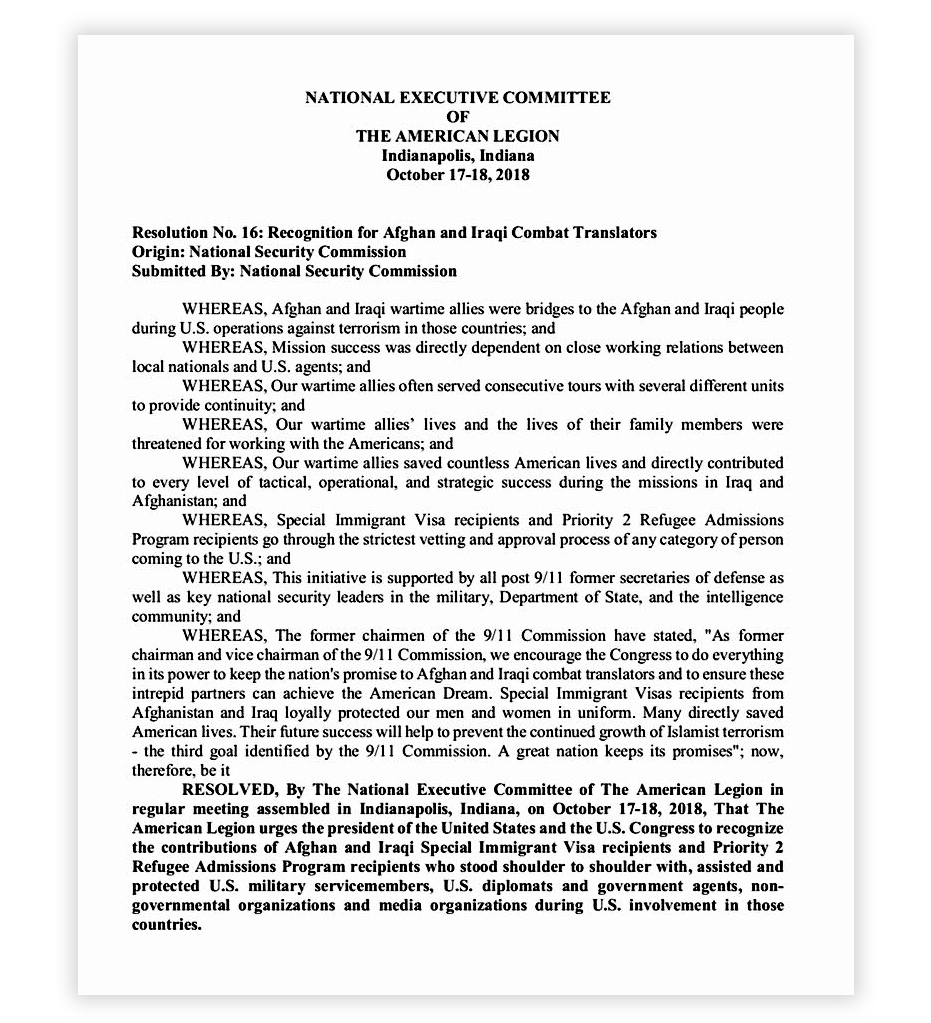

The American Legion recently issued this resolution calling on the U.S. government to boost its admissions of Afghan and Iraqi translators who had served American interests overseas. [Courtesy Ahmad Sajad Kazimi]

“They were hardcore,” Watson said. One of his first translators, whom he called Ahmed, was among his best, expanding and refining his English as he diversified and built his experience working primarily for Canadian and American forces.

“Ahmed was late a lot, especially in 2006,” Watson said. “You had to be respectful of that because the highway between Kandahar airfield (where the Canadians were based) and the city became very, very lethal, especially in 2006-2007.

A Taliban night letter threatening Kazimi for helping coalition forces. [AHMAD SAJAD KAZIMI]

“He’s like, ‘I’m so sorry, sir. I’m late because my baby died this morning. It won’t happen again.’ I knew he had a baby girl but he hadn’t talked about her very much. They hadn’t even named the child yet—they didn’t until the first birthday because infant mortality was so high. But Ahmed was like, ‘hey, I’m ready to get to work now.’ I told him to go home. Can you imagine?”

For Kazimi, the military work was varied and interesting, the food good and the money great—up to US$1,600 a month versus an average Afghan wage of $200. Now he is paying the price, living in sustained terror. His first child, a boy, arrived recently.

“My life is at serious risk,” he said. “It’s so hard to live in such an insufferable situation here in Kabul. I’m hiding every day.”

Still, Kazimi is willing to continue working for NATO forces. He said his job translating English and Dari at meetings with village elders and during compound searches, prisoner interviews and training sessions was “awesome.”

“I learned new things from my mentors,” he said. “I learned about western life. I loved my job. I knew there was a big risk but, honestly, I learned how to live good, how to help others.”

The retributions continue. Taliban recently used grenades in attacks on the homes of two interpreters in the Kandahar area, one of whom had done 10 rotations with Canadian troops. Both escaped with their lives, although one was later shot in the right hand after he was seen in a local market.

Ahmed, who had survived an IED blast, acquired a U.S. green card in 2006 and moved his family to Brooklyn, continuing to work for coalition forces in Kandahar.

“He’s a wheeler and a dealer; he had all kinds of things going on,” said Watson. “By my second or third tour, Ahmed had become director of the civilian side of Kandahar airfield. He’d moved up in the world significantly; he was a power-player in Kandahar province. And then in Brooklyn, he worked at a Home Depot.

“I think he found that less auspicious, although I’m pretty sure he was pretty great at selling paint. That dude could sell anything.”

Two of Watson’s other personal translators now live in Toronto, one of them a machinist, the other in the import/export business. Along with Ahmed in Brooklyn, all are doing well. “All three of those guys, I would do anything for.”

Kazimi said he wants to come to Canada for his family’s sake. “I want tranquillity,” he said. “More importantly, I want to gain my right to live as a Canadian citizen in Canada and work there like my other friends who are currently living there.

“I’m worried about my child’s future here. I always ask myself what if I don’t make it? What if I get killed one day, then who is going to take care of my loved ones?”

—

The second of a three-part series of Front Lines columns on Afghanistan. Don’t miss the photo essay Citizens of War in the November/December issue of Legion Magazine.

Click here to read Part 1 – Inside Afghanistan: Life and the art of the barter

Advertisement