HMS General Hunter in the line of battle with the British squadron at Lake Erie, September 1813. The brig is the subject of a new high-tech exhibition at the Welland Museum in Welland, Ont. [Illustration: Peter Rindlisbacher]

Duncan McCallum had stumbled upon the blackened ribs of what turned out to be a War of 1812 shipwreck emerging from exposed sand near the town of Southampton, Ont., 190 kilometres north of London.

Marine archeologist Ken Cassavoy (pointing) and volunteers excavate the site where HMS General Hunter was beached in 1816. The 2012 excavation yielded hundreds of artifacts, later conserved by the Canadian Conservation Institute in Ottawa. [Larry Lepage/HMS General Hunter Project]

“It was obvious to us immediately that there was a substantial part of the ship under the sand,” Cassavoy recalled in an interview with Legion Magazine. “We decided we’d go ahead and do something with it.”

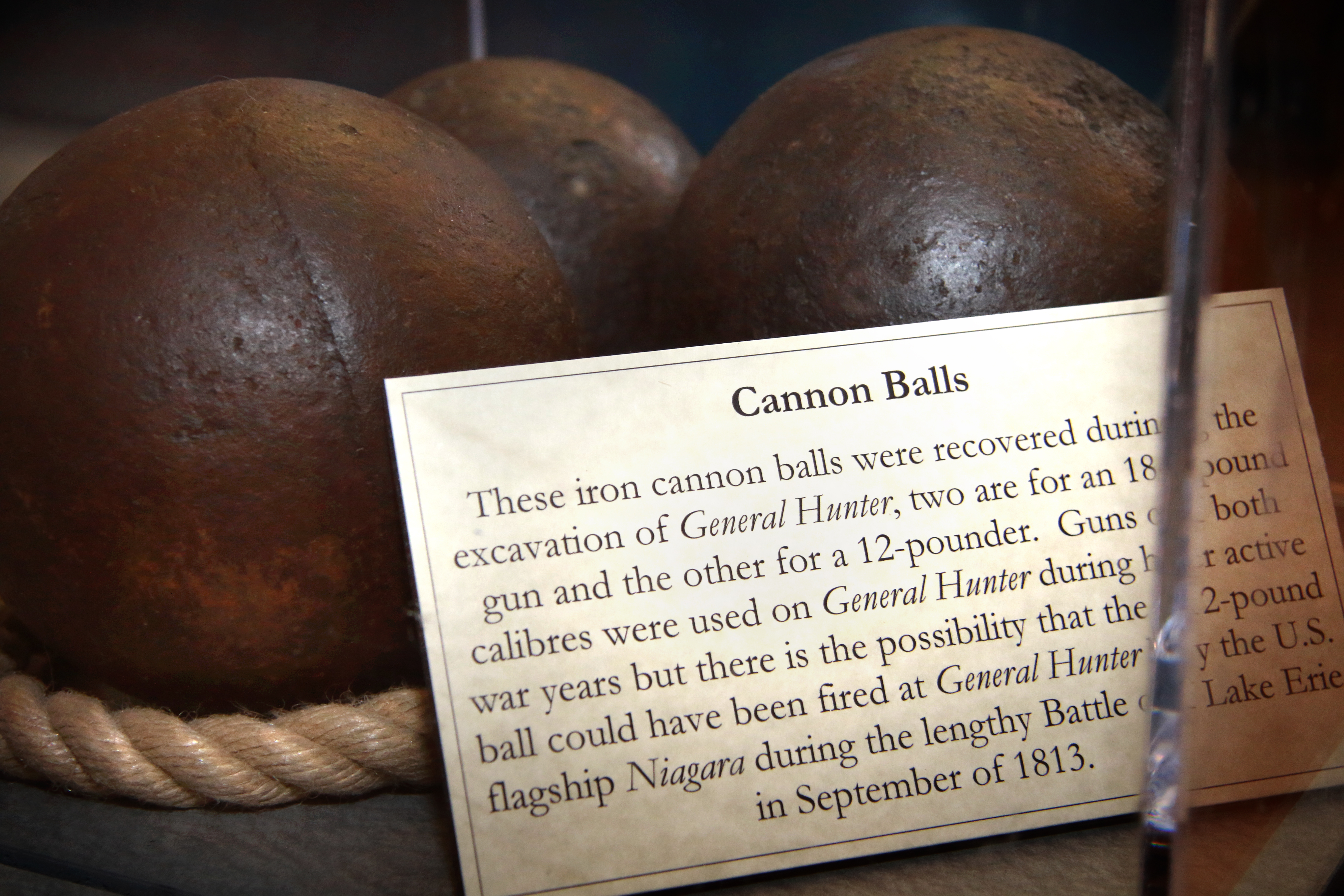

As project director, he co-ordinated a team of about 200 volunteers on a nine-week excavation in 2004. They uncovered the ship’s hull, charred timbers, a one-pound swivel cannon, iron nails and spikes, cannonballs, lead shot and a bayonet.

They also found ceramics, spoons and military buttons. Once the site was excavated, they reburied the ship’s wooden hull in the stable environment of the wet sand beach.

In 2012, it all went into a three-quarter-scale reproduction built at Bruce County Museum and Cultural Centre in Southampton to mark the war’s bicentenary. Now, HMS General Hunter is the subject of a high-tech exhibition at the Welland Museum in Welland. Ont., 25 kilometres west of Niagara Falls.

A model of HMS General Hunter at the peak of her glory, now on display at the Welland Museum. [Welland Museum]

The exhibit also includes the stories of two other War of 1812 shipwrecks explored by Cassavoy, USS Hamilton and USS Scourge, which still sit upright 92 metres down on the bottom of Lake Ontario off Port Dalhousie, Ont. The two vessels sank in a squall at 2 a.m. on Aug. 8, 1813.

Welland Museum chair Greg D’Amico says the high-tech approach is the future of museums, designed to attract new, younger audiences and introduce them to a history—the War of 1812—with which many are woefully unfamiliar.

“It’s going to be more tactile, more visual, more [auditory],” said D’Amico. “It’s not going to be ‘Here’s the ship, read about it.’”

D’Amico says he has advocated the concept from Day 1 in his role as museum chair that history in a museum setting has to be more than stories of the dead. It has to come alive.

“People who are 16 to 23 years old—what are you going to do to get them into your museum? What are you going to do to get them to see their history, their lives in a way that’s going to work for them? Especially the War of 1812.”

“We live here and these kids don’t know anything about it. They know Laura Secord is chocolates. We are trying to always strive to bring that younger generation into our museum.”

Built in 1806 at Amherstburg, Ont., General Hunter had taken part in numerous engagements, including the capture of Detroit. After her capture, General was dropped from her name and the Hunter sat out the rest of the war.

She was sold to private interests and ended up a U.S. Army supply vessel serving on the Upper Great Lakes. She was caught in an August 1816 gale after delivering general stores to Fort Mackinaw at what is now Mackinac Island, Mich., at the northern end of Lake Huron.

Her crew beached her on the Canadian side 250 kilometres into her return trip. Her skipper, seven crew and two passengers made it ashore, then rowed the ship’s boat safely to Detroit.

The wreck was later salvaged by U.S. soldiers dispatched aboard two ships. They took her rudder, anchors, major spars and as much else as they could find. Since she was beached, they were able to burn her to below the waterline. Her remains were left to the sands of time.

Marine archeologist Ken Cassavoy has spent more than 35 years exploring shipwrecks around the world, including multiple War of 1812 sites. [Courtesy Ken Cassavoy]

“There was a lot of sand in the ship at that point so they took everything off that they could,” he said, describing the cannon as small with no markings.

The brig’s story was fleshed out in documents found in archives—an unusual stroke of luck, says the archeologist.

Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry transfers his flag to USS Niagara after his flagship, USS Lawrence, was disabled while defeating the British at the Battle of Lake Erie in September 1813. [ILLUSTRATION: PERCY MORGAN/LIBRARY OF CONGRESS—LC-USZC4-6893]

“It’s so much a part of our history. For people who live here, it has so much relevance. The Battle of Lake Erie was just down at the other end of the lake here.”

The exhibition is scheduled to run at the Welland Museum through year’s end.

Cannonballs recovered during the excavation of HMS General Hunter. [Welland Museum]

Advertisement