A photo reproduction of a painting by W. Avis depicts Bell-Irving and his observer engaging enemy aircraft on Dec. 19, 1915, between Lille, France, and Ypres, Belgium. [Public domain/City of Vancouver Archives]

A “light umbrella,” the Oxford English Dictionary calls it. Delicate. Fringed with lace.

In First World War Europe, however, the Morane-Saulnier Type L Parasol was a French-built, two-seat monoplane—originally a scout aircraft that, once fitted with a single machine gun, became one of the world’s first successful fighter aircraft.

And, unlike the parasol of Mary Poppins fame, it was a rough- and rickety-looking one, at that.

This garden party was anything but highbrow, and its attendees were certainly not dainty. But for the clouds in the skies over the Western Front, there was nowhere to hide from the sun or any other threat to life and limb. And there were many.

On Dec. 19, 1915, Captain Malcolm McBean Bell-Irving of the Royal Flying Corps—one of six Vancouver brothers enlisted in Empire forces (two others also flyers)—and his observer, a Brit named Scott, encountered three of the more fearsome kind in the form of Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte aircraft, their type unknown.

“The first he drove off, the second he sent to the ground in flames and the third nose-dived and disappeared.”

Age 23 at the time, he was somewhere between Lille, in northern France, and Ypres, in the south of Belgium, where the German advance to the sea had ground to a halt in fall 1914. A salient had formed around the medieval trading centre that the Allies would keep pretty much in check until the war’s end.

For a pilot of his time, Bell-Irving was seasoned and, the evidence suggests, unflappable. He had joined 1 Squadron at Netheravon, England, in October 1914—the first Canadian to join the RFC—and had flown his first reconnaissance mission over France the following March.

He was wounded for the first time within a month, over Hill 60. He had survived at least one accident and several dogfights.

On this day, Bell-Irving shot down one of his foes and drove off the other two. He was wounded again, but continued to fly, and would be awarded the Distinguished Service Order, the first Canadian-earned decoration in the Royal Flying Corps.

“For conspicuous and consistent gallantry and skill during a period of nine months in France, notably on 19th December, 1915, between Lille and Ypres, when he successfully engaged three hostile machines,” reads his citation. “The first he drove off, the second he sent to the ground in flames and the third nose-dived and disappeared.

“He was then attacked by three other hostile machines from above, but he flew off towards Ypres, and chased a machine he saw in that direction.”

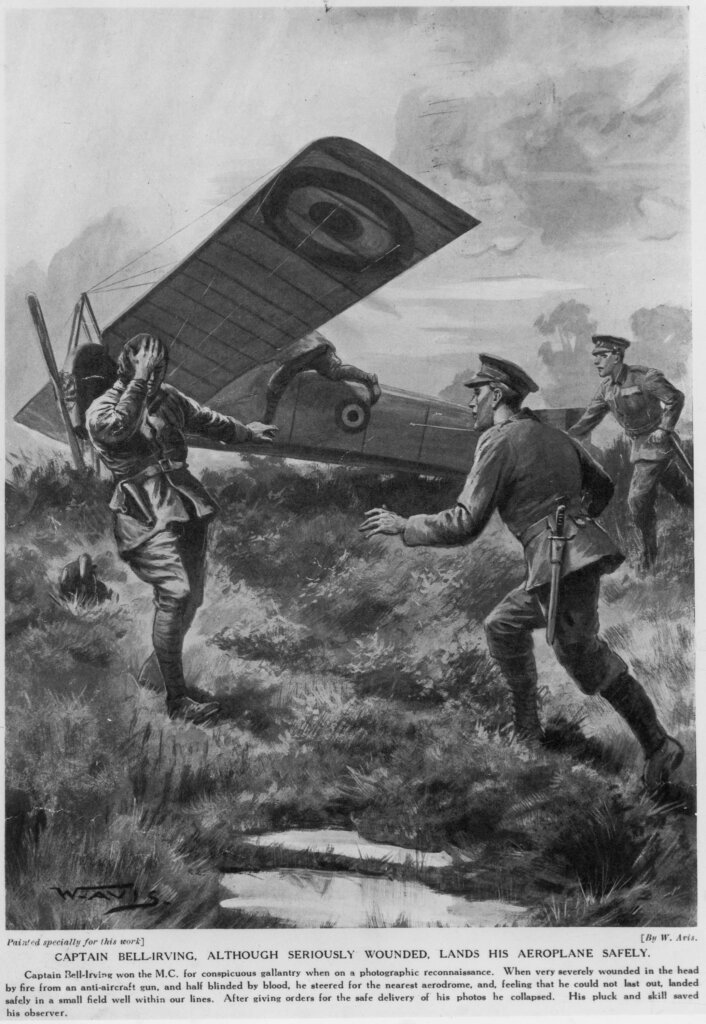

A depiction of a wounded Captain Bell-Irving after landing his Morane scout plane in a small field behind Allied lines on June 20, 1916. [Photo: Public domain/City of Vancouver Archives]

In those early days, wartime flight consisted of simple planes and balloons, used primarily in scouting and photographic mapping of enemy positions. The first crews of rival reconnaissance aircraft exchanged nothing more belligerent than smiles and waves. Soon, however, they began tossing grenades and even grappling hooks at each other.

The first recorded incident in which an aircraft was brought down by another involved an Austrian reconnaissance plane rammed on Sept. 8, 1914, by Russian Pyotr Nesterov on the Eastern Front. Both aircrews were killed in the dual crash.

Battling freezing cold, buffeted by unpredictable winds and weather in flimsy, relatively unreliable airframes, and increasingly threatened by their rivals’ incursions, pilots began firing handheld weapons—pistols and shotguns, mainly—at enemy aircraft, although they were rarely an effective means of attack.

Once, when Bell-Irving’s revolver misfired, he is said to have thrown the weapon at a German pilot, hitting him in the head.

By early 1915, the British army reckoned it would need some 50 squadrons—700 planes.

With a homeland so vast and wild, it was only natural that Canadians took to the skies early and often. The First World War—the first industrialized war—would prove the catalyst that propelled Canada’s fledgling aviation industry to new heights.

Like no other war before it, the Great War fostered unparallelled advances—in medicine, technology, weaponry, machinery and, perhaps more than any other field, aviation.

Just a decade after the Wright brothers achieved history’s first powered flight, the airplane had become a weapon of war and the focus of an arms race.

Warplanes started out as rudimentary aircraft with open cockpits and limited instrumentation. Pilots, quite literally, flew by the seat of their pants, without parachutes.

The aviation industry, however, was in rapid growth, in constant evolution, designs and performance improved with each new aircraft.

By early 1915, the British army reckoned it would need some 50 squadrons—700 planes. The British secretary of state for war, Horatio Herbert Kitchener, ordered it to double its request.

A Morane-Saulnier Type L Parasol with RFC markings. This French-built, two-seat monoplane became one of the world’s first successful fighter aircraft. [Photo: SDASM/flickr.com]

By war’s end, Allied nations were outproducing the Germans by nearly 5:1 in aircraft and better than 7:1 in engines. Britain was coming out with 31 times more planes a month than it had owned when the war started. The RAF was the first independent air service, and the largest.

“Pilots were needed in ever-increasing numbers to fly the new machines and replace casualties,” the BBC reported in 2014. “Although the [Royal Flying Corps] was relatively small, their ratio of losses was at least as high as in the infantry.

“But there was never a shortage of volunteers either to fly as a pilot or as an observer. The romance of flying was an attractive proposition, it avoided the tedium of life in the trenches and offered a novel way of going to war.”

Flying with British units, Canuck aviators acquitted themselves exceptionally well in history’s first aerial confrontation between countries.

There were 171 Canadian flying aces between 1914 and 1918—airmen with five-plus aerial victories, or kills. Four of the Top 12 were Canadian, three Top 10: Billy Bishop with 72 kills; Raymond Collishaw (60); Donald McLaren (54); and, at No. 12, William Barker (50). Twenty-four Canadians scored 20 or more.

Canadian flyers were awarded at least 495 British decorations for gallantry, including three Victoria Crosses—Bishop and Barker among them—and 193 Distinguished Flying Crosses, plus nine bars.

A photograph of the Bell-Irving siblings: (from left) Roderick, Henry, Aeneas, Richard, Malcolm, Alan and Isabel (centre), who served as a nurse in Lady Ridley’s Hospital for wounded officers in London. [Vancouver Sun Archives]

He was transferred to Lady Ridley’s Hospital in London where he lay in and out of consciousness for three months. Bell-Irving’s wound, a piece of shrapnel in the brain that had temporarily affected both his sight and memory, kept him out of action for 18 months.

Once reactivated, he went to the School of Special Flying at Gosport, England, commanded by his brother, Alan Duncan Bell-Irving, for a refresher course. Impatient to get back to France, he talked his way into soloing on a Sopwith Camel and spun it into the ground from a left-hand turn. It was a typical mishap attributable largely to the plane’s stubby fuselage and the torque of its powerful rotary engine.

But Bell-Irving suffered further head injuries and lost his left leg above the knee after the accident. The American brain surgeon who had advised on his earlier head wound saw him in a London hospital on May 23, 1918.

The doctor reported that Bell-Irving “only vaguely recalled me—suffering the tortures of hell from neuromats in the stump of his amputated leg…. Still the same charming person, however, despite his thoroughly drugged condition.”

Bell-Irving eventually returned to Canada where he served as liaison officer with the RFC, responsible for all matters affecting Canadians who had been seconded from the army.

By the time the aircrew who survived the Great War came home, many had caught the flying bug, or at least saw opportunity in an emerging industry.

All six Bell-Irving brothers were decorated for valour. All but one, Major Roderick Ogle Bell-Irving, survived the war. Arthur, a captain, achieved ace status with seven aerial victories and served in WW II with the Royal Canadian Air Force. But not Malcolm.

He ended the war at the rank of major. He doesn’t appear in the list of Canadian aces and his total victories are unrecorded. He died June 11, 1942, in Oak Bay, B.C.

By the time the aircrew who survived the Great War came home, many had caught the flying bug, or at least saw opportunity in an emerging industry that, in a country such as Canada, offered tantalizing room for development.

Between the wars, aircraft design continued to evolve, records were set and broken, early bush and floatplanes hit production lines, and the airplane began to open Canada’s vast hinterlands to easier exploration, exploitation and settlement.

Versions of a new Canadian military flying force came and went until, in 1924, a reconstituted CAF was granted royal sanction by King George V.

The RCAF was forged on a growing aviation culture of hinterland stick jockeys, airmail pilots, transport captains and high-flying adventurers. At its WW II peak, the RCAF was the world’s fourth largest air force, and had asserted itself as a respected, if not feared, hunter and protector.

Advertisement