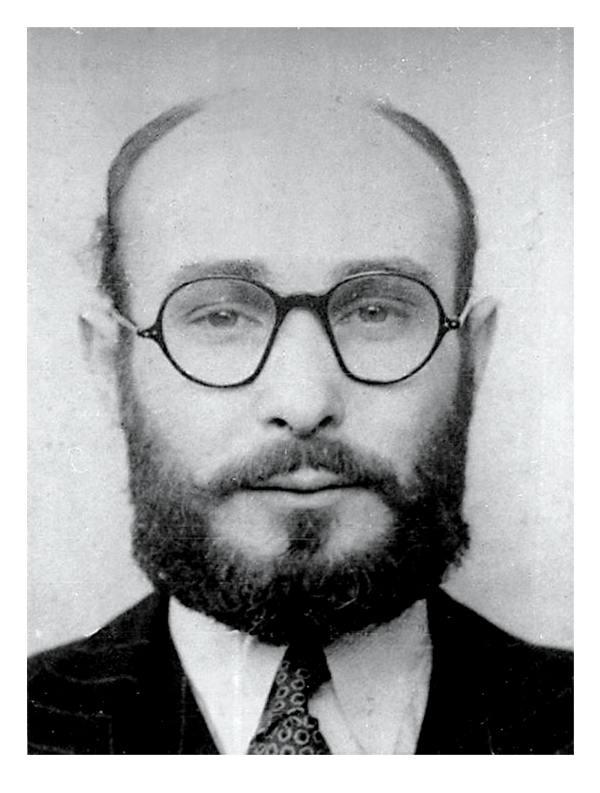

Juan Pujol became the most successful double agent of the Second World War, playing a critical role in D-Day’s success

AGENT GARBO

The brutality of the Spanish Civil War led poultry farmer and reluctant Spanish soldier Juan Pujol to despise totalitarian regimes. With the success achieved by Nazi Germany at the outset of the Second World War, Pujol wrote: “I wanted to start a personal war with Hitler. And I wanted to fight with my imagination.”

Pujol resolved to serve England as a spy. British agents in Madrid, however, rebuffed all his approaches. Exasperated, to get things rolling, Pujol finally volunteered to spy on England for the Germans.

Having effectively established himself as an independent double agent, Pujol set up in Lisbon and began showering the Germans with information gleaned from an ever-growing network of fictional sub-agents. Having never visited the United Kingdom, he relied on a Blue Guide to England along with reference books and magazines from Lisbon’s library. He told his German controller there were men in Glasgow willing to “do anything for a litre of wine.” The German apparently knew no more of Glaswegian drinking habits than did Pujol.

In April 1942, Pujol finally contacted Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service and moved to London. The service’s Spanish-speaking Tomás Harris became the handler of agent “Garbo.” Together they created an elaborate network of 27 fictional sub-agents with full life stories. Harris and Garbo jointly filed 315 letters. Each ran about 2,000 words and was written in Pujol’s trademark florid, verbose style. The material was so voluminous that the Germans ceased further attempts to establish spies in England.

One message sent in November 1942 cemented Pujol’s credibility with the Germans. Timed to arrive just slightly too late, the message warned that an Allied invasion fleet was headed for the Mediterranean. Despite Operation Torch’s success, the Germans declared the intelligence provided was “magnificent.” By 1944, the Germans believed Pujol was controlling an extensive network of tried, tested and trustworthy agents.

This positioned Garbo perfectly for a masterstroke supporting Operation Fortitude—the deception whereby American General George S. Patton assembled a fake invasion army directed toward Pas-de-Calais, France. Even after D-Day on June 6, Pujol’s messages kept the German high command believing that the Normandy invasion was a ruse. Consequently, two armoured and 19 infantry divisions were held in Pas-de-Calais.

Fearing his double-agent role was in danger of being revealed, Pujol went to ground in September 1944. That December, he was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire. After the war, he moved to Venezuela and died in 1988.

AGENT ARABEL

In 1941, 29-year-old Spaniard Juan Pujol convinced German intelligence officers in Madrid to send him to London to build a network of agents capable of providing critical intelligence. Pujol declared himself a dedicated fascist, ready to die for the Führer’s “new world order.”

After some initial skepticism, Pujol was recruited and code-named “Arabel.” His training consisted largely of a crash course in secret writing, whereby invisible ink messages were hidden in an innocuous letter. Pujol insisted on absolute control over the timing of his contacts with the German controllers because “any leakage…would ruin his cover in England,” as British intelligence officer Tomás Harris put it.

On July 19, 1941, Pujol arrived safely in England. Arabel’s reports were supposed to reach Madrid via the diplomatic mailbag of neutral Spain’s London embassy. Pujol vetoed this system, instead recruiting a civilian airline employee to carry mail to Lisbon and then forward it by regular post. This, Pujol said, avoided the reports passing through British censors. From Madrid, his intelligence was passed to Berlin and found to be “substantial and plausible.”

In November 1942, warned by his sub-agent working on the Clyde docks in Glasgow, Pujol sent an airmail message that an amphibious invasion force with ships painted in Mediterranean camouflage had just left the harbour. The message was delayed and Operation Torch’s landings in North Africa succeeded. Although sorry the intelligence “arrived too late,” the Germans said that Pujol’s “last reports were magnificent.”

Knowing an Allied invasion of France was coming, Pujol was pressed for information. Between January 1944 and D-Day, Arabel—now reporting by wireless—sent 500 messages—four a day. With 27 “agents” under command, Pujol’s reports detailed a massive invasion buildup.

On June 5, Arabel warned his German wireless contact to stand by for an urgent message at 3 a.m. on June 6. When the German failed to be manning his set at the established time, Pujol raged: “I cannot accept excuses or negligence. Were it not for my ideals, I would abandon the work.” Three days later, he advised Germany that the Normandy invasion was a ruse. The real strike would be delivered by First U.S. Army Group at Pas-de-Calais.

On July 29, 1944, Germany awarded Pujol an Iron Cross, via radio. He expressed “humble thanks” for the honour of which he was “unworthy.” In September 1944, Pujol went underground for fear of arrest. But his fictional network of agents continued to provide intelligence the Germans valued until war’s end.

Advertisement