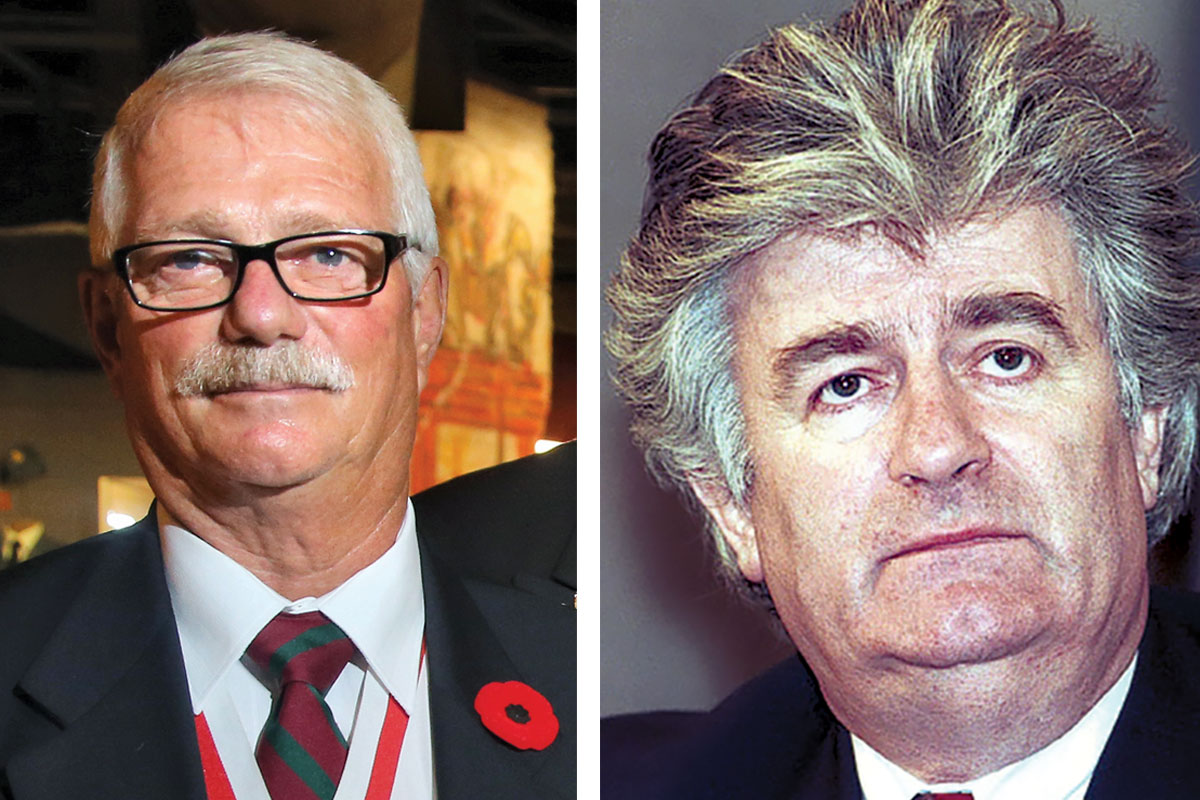

On Dec. 24, 1993, Sérgio Vieira de Mello, the United Nations Protection Force’s director of political affairs in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, summoned his new military aide, Canadian Major John Russell, to his office. “John, we’re going to break the siege,” the diplomat declared. “I want you to find a way to get people out.”

“Okay, sir,” Russell replied, “but keep in mind that it was just two days ago I learned where Sarajevo airport was.”

The Bosnian capital had been surrounded by Bosnian Serb forces since April 5, 1992, so Russell faced a daunting and dangerous challenge. Vieira de Mello quickly arranged a meeting with the Bosnian Serb authorities at their headquarters in Pale, a community outside Sarajevo. “This is John Russell,” he told them. “In my absence, he speaks for me and the United Nations.”

The diplomat then left the soldier to organize “the train,” a convoy system that would transport Bosnian civilians out of the besieged city to waiting UN aircraft unloading humanitarian aid at the city’s airport. The airport was under Bosnian Serb control. Russell started with trials to time how long it took to travel the city’s main boulevard—nicknamed “Sniper’s Alley”—to the airport, stopping at checkpoints along the way.

To facilitate the humanitarian effort, the Bosnian Serbs had allowed a one-hour window for UN Hercules or Ilyushin cargo planes to fly in each morning and afternoon. Russell’s convoys—consisting generally of one or two heavily armoured vehicles—were often subjected to shell and sniper fire along the route. At times, Russell hit 160 kilometres per hour to escape incoming fire.

Russell’s most difficult responsibility, however, was deciding who would be evacuated. He later testified that he had to literally choose who would live and who would likely die based on circumstances beyond his control. As word of the convoy spread, some tried to bribe Russell with money or sex and were all immediately rejected. Others were rejected because they had terminal illnesses or were of fighting age and likely trying to desert.

“I saw people I turned down lying dead on the street,” he said. “They died at my hands, indirectly.” Over the course of 110 days, until replaced by Canadian Captain Pat Dray, Russell managed to spirit 298 people out of Sarajevo. Among them was Ivanka Kolak-Lončarević, whose parents later thanked Russell by presenting him with an Olympic torch used in the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Games.

They have to know that there are 20,000 armed Serbs around Sarajevo,” said Radovan Karadžić in a UN-intercepted radio message. “They will disappear. Sarajevo will be a black cauldron, where 300,000 Muslims will die. It will be a real bloodbath.”

In another intercept, he declared that the Bosnian Muslims—known as Bosniaks—“should be trashed. That people will disappear from the face of the earth…. This is a fight to the finish, a battle for living space.”

Karadžić was the first president of the self-declared Republika Srpska, which the Bosnian Serbs tried to unify with Serbia. He was also the mastermind behind the ethnic cleansing campaign that during the Bosnian War from 1992 to 1995 forced two million people from their homes and led to thousands being held, tortured and raped in detention camps.

As the Bosnian Serb armed forces commander, Karadžić authorized the siege of Sarajevo. In March 1995, he unleashed Serbian fighters into the UN-declared safe haven of Srebrenica with instructions to “create an unbearable situation of total insecurity with no hope of further survival or life for the [town’s] inhabitants.” On July 12, thousands of Bosniak men and boys were taken prisoner while the town’s women, children and elderly were relocated by bus to Bosniak-held territory. Over the following four days, 7,000 to 8,000 of the prisoners were executed. Many of the bodies were mutilated.

The Srebrenica atrocities were just part of the genocide by Bosnian Serbs that ultimately killed an estimated 100,000 Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats. Many others were brutalized and rape was widely used as an instrument of terror. During the 44-month Siege of Sarajevo—from April 5, 1992, to Feb. 29, 1996—13,952 people were killed.

Indicted on 11 charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other atrocities, Karadžić was forced out of the presidency in early 1996 and fled into hiding. He was finally arrested on July 21, 2008, in Belgrade.

A series of trials before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague began shortly after his arrest and culminated in his conviction on 10 of the charges on March 24, 2016. He was sentenced to 40 years’ imprisonment. Karadžić denied any guilt, insisting his actions were aimed at protecting Serbs. In his ruling, the presiding judge said Karadžić was the only person with the power to have stopped the Srebrenica murders, but instead he “significantly contributed” to “killing the Bosnian Muslim males.”

Advertisement