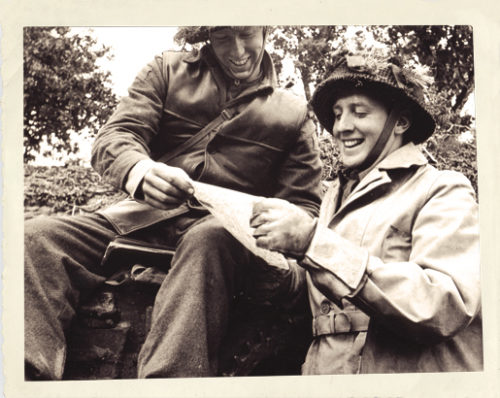

Brothers Doug and Pete Kennedy of Waterloo, Ont., get a chuckle out of a letter from home while in France during the Second World War. [LAC/C053582]

“It was long hours and hard work,” said Harry Gower, who unloaded mail in England. But it was also rewarding. “They were always thrilled to get mail,” he said in one of many Memory Project interviews quoted here. “It was a big deal for them, because you were away from your family for several years.”

“Everybody was dedicated to getting that mail out,” said Joseph P. Tobin, who sorted letters and packages during the Italian campaign.

Military staff were always on the move, “letters and parcels following them around, trying to catch up,” recalled Louis R. Brochet. Mail for field personnel “was mostly all redirected because by the time the letters got there, the people were gone.”

Consequently, mail sometimes arrived looking the worse for wear. “I had parcels that looked like beat-up old footballs,” said Charles S. Wood.

The Canadian Legion, among others, sold cigarette gift cards to soldiers’ friends, families and well-wishers back home. They could be traded in for cigarettes at postal corps tobacco depots overseas. A dollar would buy 300 cigarettes, $2.50 would buy 1,000. The cards eliminated thousands of parcels from the mail system.

The post kept Alfred Monnin in touch with his wife. “It was slow. I would write to her about once a week. Sometimes, I would receive three, four or five letters all at once since the delivery wasn’t very reliable.”

Members of the Pioneer Corps unload Christmas mail at 2 Canadian Corps Army Post Office in the Netherlands in December 1944. [B.J. GLOSTER/LAC/PA-137637]

Mail call was irregular. Edward A. Jesseman was in the back of a truck travelling through a Dutch forest when he was hailed by a familiar voice. “‘Ed! Do you know that you’re a father?’ The mail hadn’t got through to me yet,” but it had reached Jesseman’s brother-in-law who relayed the news as the truck drove by.

Not all the mail delivered brought good news.

Malcolm MacConnell of Bomber Command eagerly opened his mail, expecting good news that his sister had been accepted into the nursing corps.

“It contained a telegram from my mother saying that my brother Bud had been killed,” said MacConnell. Although he had become inured to comrades’ deaths, “when my brother was killed, that was deep, deep, deep, deep grief.”

Parcels were always welcome when they arrived in theatre—or at home.

“That wonderful wife of mine sent parcels all the time,” which would arrive in batches, recalled Arthur F. Haley. “And in those parcels was the thing I liked—oatmeal cookies, as big around as a baking soda can.” He shared the joy with comrades.

Lorne Barlett sent a surprising gift from the battlefield to his father in Canada. After asking permission, he and his company sergeant-major broke down a captured German Schmeisser machine pistol to be mailed home in three parcels. “My dad got it just two days before Christmas.” A lasting gift, it was subsequently passed down to Barlett’s own son.

To this day, the Canadian Forces Postal Service establishes post offices on ships and wherever personnel are deployed abroad—and offers free morale mail service at base post offices for families who want to send letters and care packages to deployed personnel.

Advertisement