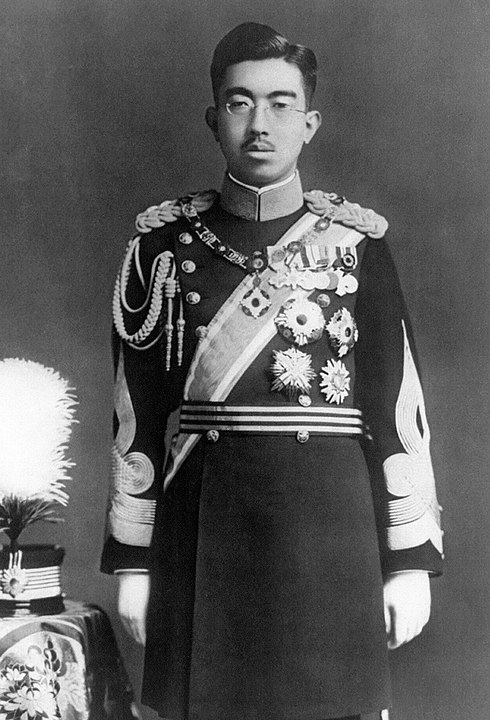

Emperor Hirohito, known posthumously as Emperor Shōwa. [Wikimedia]

Although Japan had technically been part of the Second World War since signing the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy in September 1940, its war with China had commanded its attention.

Japan had grand territorial ambitions in Asia. It invaded and absorbed Manchuria in 1932 and had been at war with China since 1937. In 1941, alarmed by imports of war materiel into China, it cut off supply lines in French Indochina.

The United States, Britain and the Netherlands responded by putting an embargo on oil exports to Japan. Its expansion plans threatened by loss of a steady supply of oil, Japan concluded that decisive simultaneous strikes would tie up the United States navy and allow them to seize oil production facilities in the East Indies, then go on to conquer southeast Asia.

Everything was done in the name of the emperor, but questions remain to this day about Hirohito’s involvement in the conflict that cost more than three million Japanese lives and ushered in the atomic era.

Was the emperor an authoritarian leader who should have been tried for war crimes, or was he a proponent of peace whose ceremonial role helped Japan toward postwar prosperity?

Born in 1901, Hirohito began his reign after the death of his father in 1926, ushering in the era of Shōwa, or Enlightened Peace.

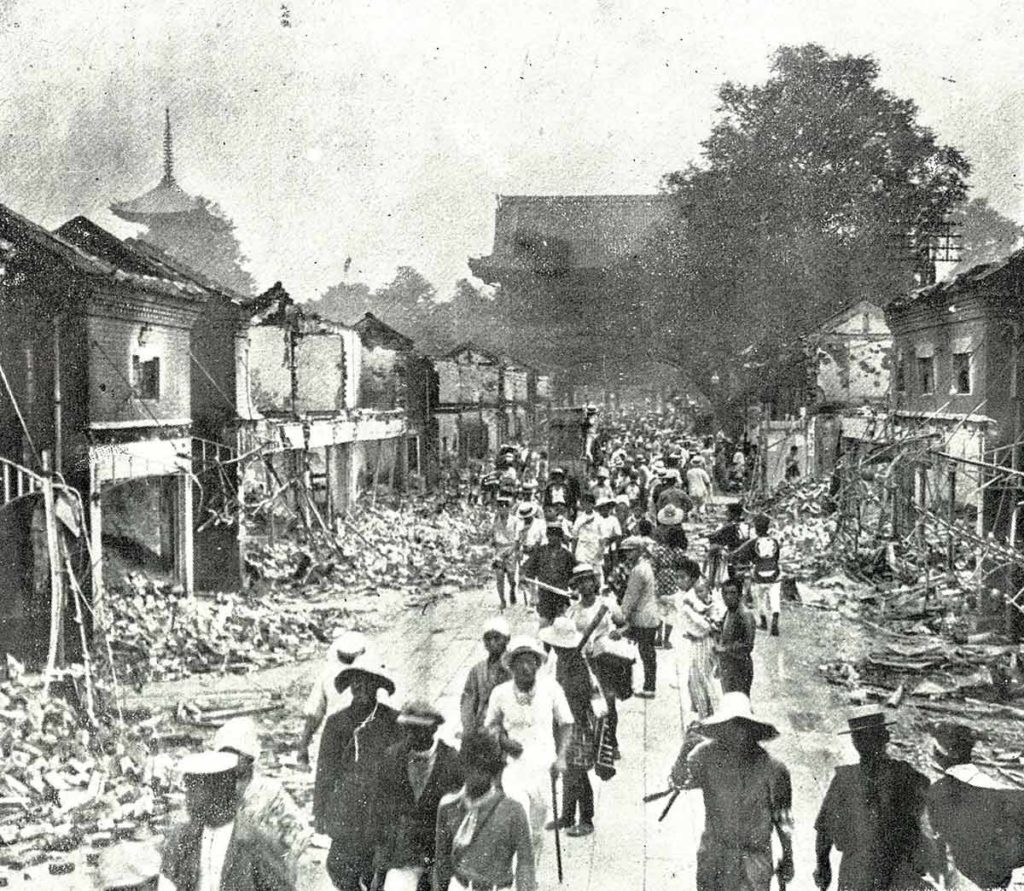

It was anything but. Still recovering from an earthquake that devastated Tokyo in 1923, Japan was in financial crisis and there was dissension among military leaders that Hirohito was powerless to settle.

Damage caused by a 1920 earthquake in the area around Sensō-ji temple in Asakusa, Japan. [Wikimedia]

But the constitution also unburdened the emperor of the weight of that work, including policy-making, to cabinet. Cabinet ministers would reach a consensus on issues and the emperor rubber-stamped their decisions.

The military was supposed to have civilian oversight, but since before Hirohito’s birth, the army and navy had veto power over formation of the cabinet.

The military acted on its own volition in 1928 in killing the governor of Manchuria in hopes of extending Japanese influence in northeast China. Three years later, again without leave of the government, the Japanese army seized Manchuria and set up a puppet state.

“From this point onward until 1945 the military would be in control of Japan’s foreign policy,” wrote Kazuaki Suhama in a 2020 paper examining Hirohito’s military and political role in Japan.

In February 1936, army officers assassinated several cabinet ministers and nearly killed the prime minister of Japan. Hirohito demanded a stop to the killing, a step he would take again at the end of the Second World War.

Germany surrendered in May 1945, but Japan was determined to fight on.

Unable to garner support of the Western world in its territorial ambitions in China and southeast Asia, Japan held an imperial conference in September 1941 to decide what to do about the United States and the British Empire.

Japan decided to go to war on Dec. 1, 1941, against the United States, Britain and the Netherlands. A week later it launched simultaneous surprise attacks on the U.S. fleet in Pearl Harbor and on the British Hong Kong Garrison, only recently joined by nearly 2,000 Canadian soldiers.

The USS Arizona burning after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941. [Wikimedia]

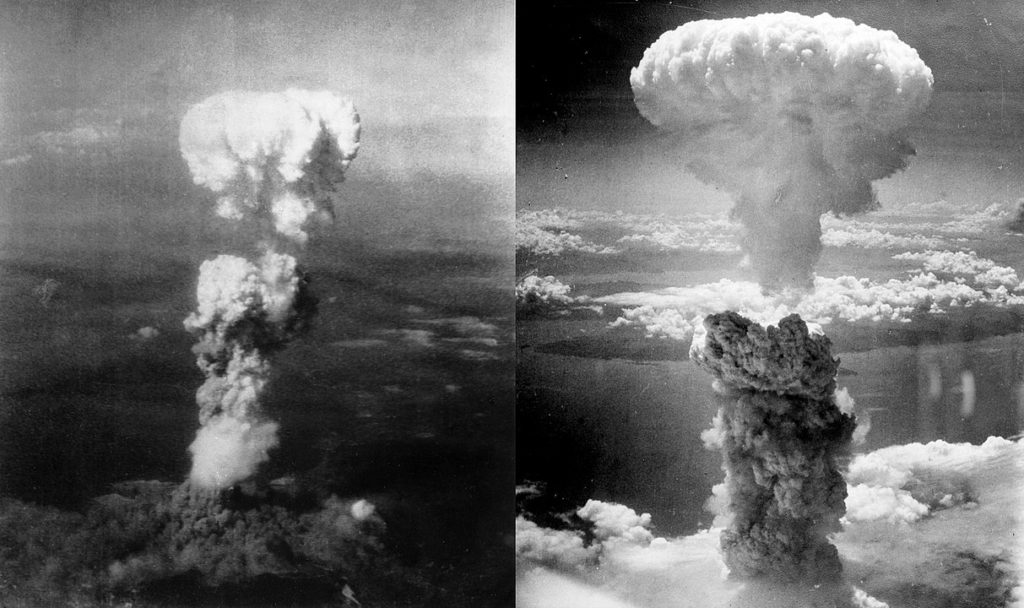

The Allies demanded Japan’s unconditional surrender in July of that year, threatening “prompt and utter destruction.” Unable to come to internal agreement, Japan demurred.

On Aug. 6, the Allies dropped a nuclear bomb on Hiroshima and three days later, Nagasaki. That same day the Soviet Union declared war on Japan.

Mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. [Wikimedia]

Hirohito broke the impasse, recording a broadcast telling his people they must “endure the unendurable” and surrender. The recording had to be hidden away while an attempted coup was put down, but the speech was broadcast on Aug. 15.

After the war, there was a call for Hirohito to step down, but U.S. General Douglas MacArthur believed the Japanese people needed the continuity symbolized by the emperor. Under a new constitution in 1947, the emperor was reduced from imperial sovereign to constitutional monarch, with a much more clearly defined role as head of state, not government.

While scholars have argued about the extent of his power during the war, Hirohito himself said he made decisions on his own only twice, in demanding suppression of the 1936 coup and in bringing the Second World War to a close.

The debate was taboo in Japan while Hirohito lived, but the emperor knew he was being blamed for his part in the war. He told confidants that “there is nothing good in living long.”

He died on January 7, 1989, ending 63 years on the throne, Japan’s longest-reigning emperor.

And the debate about his role goes on, more than a generation after his death.

Entries from a recently released diary of Saburō Hyakutake, an admiral and aide to the emperor, cast Hirohito as conflicted and ultimately a strong proponent of war with the West. For more on this, see next week’s edition of Front Lines Weekly on Dec. 15.

Advertisement