The U.S.-built Bell P-39 Airacobra, delivered in numbers by Allied convoy, was a stalwart of the Soviet defence against Nazi Germany’s invasion. Its Soviet pilots collected the highest number of kills attributed to any U.S. fighter type flown by any air force in any conflict. [Wikimedia]

In the summer of 1941, Nazi Germany launched an invasion on the Soviet Union, despite a non-aggression pact signed by the two countries in 1939.

The Soviets were unprepared when some 3.5 million German troops attacked along a front stretching nearly 3,000 kilometres. The USSR turned to the Allies for help.

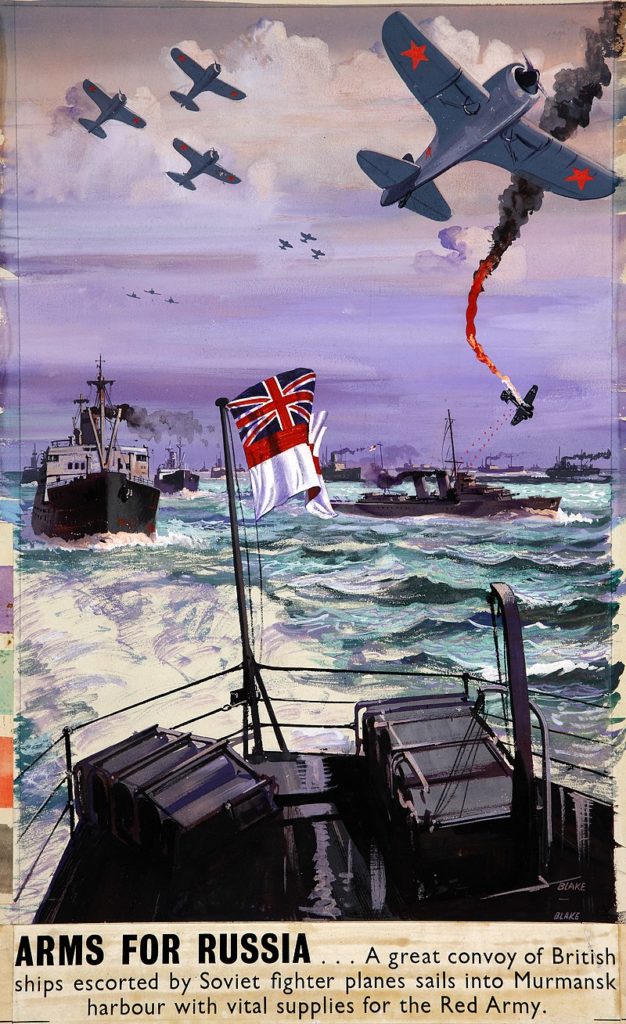

For the previous two years, ship convoys had been crossing the Atlantic to supply Britain with men and materiel to support its war efforts. Now they would also travel more northern waters to supply the beleaguered Soviets through the ports of Murmansk and Archangelsk near the Arctic Circle.

Winston Churchill called it “the worst journey in the world.”

In four years, some 1,400 ships in 78 convoys made the journey to the USSR and back, delivering more than four million tonnes of supplies, including food, materiel, trucks and tractors, 5,000 tanks, 7,000 warplanes, telephone wire, railway engines and clothing. The cost was high—the lives of about 3,000 Allied sailors, along with around 100 merchant vessels, two navy cruisers, six destroyers and eight other escort ships.

Yousuf Karsh photographed Winston Churchill after the British prime minister addressed the Canadian Parliament in December 1941. [Karsh/Wikimedia]

Winston Churchill called it “the worst journey in the world.”

The pressure on the convoys continued until the end of the war.

Waffen SS vehicles, artillery and machine gunners. [Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1970-025-28 / CC-BY- SA 3.0 -wikimedia.org]

“The Allies knew that there were a number of U-boats off the entrance to Kola Inlet and that JW-66 would most likely have to force its way into Murmansk,” wrote naval historian David Syrett in The Last Murmansk Convoys, 11 March-30 May 1945.

The escorts were vigilant, dropping depth charges after sonar contacts and ordering aircraft to investigate enemy planes on the horizon.

A dozen U-boats had gathered at the mouth of Kola Inlet.

On April 24, a cluster of U-boats was detected 40 kilometres ahead.

The route to Murmansk was cleared for the convoy, with the escort ships dropping more than 400 depth charges in response to sonar readings. The Allied ships were not attacked on their way into the inlet.

The return trip was a different matter.

A Soviet horse-drawn carriage stuck in deep mud near the front. [Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-289-1091-26 / Dinstühler / CC-BY-SA 3.0]

A dozen U-boats had gathered at the mouth of Kola Inlet, ordered to lurk in shallow waters, where they were less likely to be detected, until they could pounce.

Rear-Admiral Angus Cunninghame Graham knew the U-boats were there. He aimed to deceive them about the convoy’s departure by ordering anti-submarine vessels to drop depth charges in the middle of the night of April 27-28 and sending multiple fake radio messages, just as they would have if the convoy was actually leaving.

“I was very lucky because I did not go into the sea. Had I done so I would not be writing this.”

The Germans weren’t fooled.

The convoy left on April 29, preceded by four escort ships sailing in line a couple of kilometres apart, searching for U-boats. U-307 was detected, attacked and forced to the surface. After a brief fight, the sub was taken, survivors picked up and the boat destroyed.

A half-hour later, an acoustic homing torpedo from U-968 hit HMS Goodall and blew up its magazine.

Crew members clear the frozen forecastle of HMS Inglefield during the notorious Murmansk Run. [Lieut. (N) F.A. Hudson/Wikimedia]

“I was very lucky because I did not go into the sea,” said Lovitt, who sustained a fractured pelvis in the attack. “Had I done so I would not be writing this. Of the crew of about 140, only 38 survived.”

While Goodall survivors were being rescued, three escorts targeted U-286 with anti-submarine weapons.

The convoy, now designated RA-66, cleared the inlet early in the morning on April 30.

On May 2, U-boats were informed of Hitler’s death and on May 5 they were ordered to stand down.

The Allies sent another convoy after the war ended—escorted by four destroyers and two escort groups, as well as an aircraft carrier just in case any U-boat captains decided not to surrender.

The journey was uneventful. The convoy arrived in Murmansk on May 20 and had a safe journey home, arriving back in Scotland on May 30.

Advertisement