“Considerable excitement has been reported to me arising out of the unexpected appearance of the air service machines yesterday. No information has reached us regarding the addition of this service to the garrison. This I would be glad to get as the fortress is equipped with anti-aircraft defences. Enquiries from the civil population make it apparent that some notification is expected by the public.”

The letter of Aug. 25, 1918, from the Halifax Citadel senior military staff officer to naval authorities was clear: unless they got prior notification of an aircraft flying over the city, it could be shot down as a suspected enemy airplane.

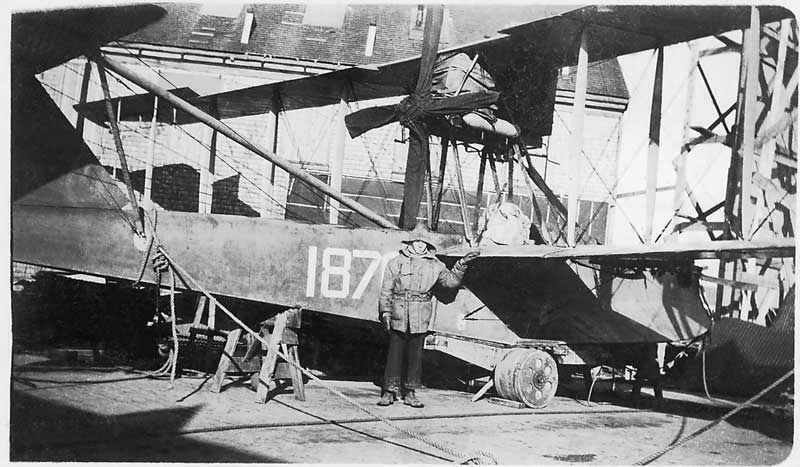

A U.S. navy Curtiss HS-2L flying boat (above) sits on the launching ramp at the American base on Baker’s Point (opposite) in Eastern Passage, N.S.[Shearwater Aviation Museum]

The aircraft that had so startled the civilian and military populace of Halifax were two United States Navy (USN) Curtiss HS-2L flying boats. They were based at Baker’s Point in Eastern Passage, across the harbour from Halifax.

But what were they doing there?

The story of how American naval aircraft came to be at Baker’s Point has its beginnings in Germany’s introduction of an anti-shipping campaign during the First World War. Germany had commenced the first large-scale use of subs, or unterseebooten—

U-boats to the Allies. Allied shipping losses shot up astronomically.

Germany actually conducted two separate unrestricted anti-shipping campaigns during the war. The first ran from February to September 1915 and met with considerable success, sinking almost a million tons of shipping. It was abandoned only after the outcry in the U.S. over the sinking of the British passenger liner Lusitania on May 7, 1915. The 1,200 dead included 128 Americans.

A U.S. navy Curtiss HS-2L flying boat (above) sits on the launching ramp at the American base on Baker’s Point (opposite) in Eastern Passage, N.S.[Shearwater Aviation Museum]

But on Feb. 1, 1917, the German high command instituted another unrestricted U-boat campaign, believing it had enough submarines to force Britain to capitulate. For the campaign to be successful, however, U-boats had to be used ruthlessly; against belligerent and neutral, against warship, merchantman and liner, in British waters or bound for Britain. Although the Germans realized attacking all vessels could bring the U.S. into the war, it was a risk they were prepared to take.

“An attack by any one of the new enemy submarines might be expected in Canadian waters any time.”

This declaration greatly concerned the Canadian government and, at a meeting on Feb. 10, an interdepartmental committee recommended the formation of a Royal Canadian Navy air arm for east coast defence. Two days later, the committee established a minimum requirement for seaplane stations at Halifax and Sydney, N.S.

Ottawa requested British assistance in fleshing out the proposal, and the Brits sent an experienced naval aviator to study the idea. In the end, his detailed paper recommending a naval air arm of 300 men and 34 seaplanes, stationed at two bases—at a cost of $1.5 million—was rejected by Canada. It was deemed to cost too much money, men and materiel.

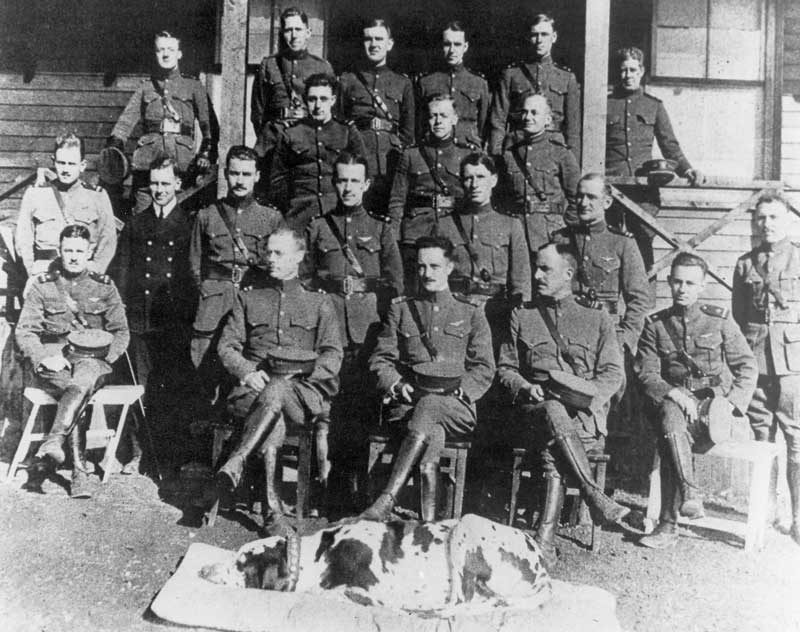

Byrd sits front and centre with his officers at the station in 1918 [Shearwater Aviation Museum]

The hoisting of the Stars and Stripes signalled the commissioning of Byrd’s command as Officer-in-Charge, U.S. Naval Air Force in Canada.

Meanwhile, to counter the U-boat threat, the Royal Navy reintroduced the convoy system and established other anti-submarine defensive measures, such as decoy vessels (ships with concealed weapons known as “Q-ships”) and putting deck guns on merchants. Still, shipping losses to U-boats continued to mount.

Then, in January 1918, the Royal Navy told Ottawa that “an attack by any one of the new enemy submarines might be expected in Canadian waters any time after March.” A subsequent message on March 11 reiterated the danger and suggested various countermeasures.

These included building seaplanes and the establishment of airbases for coastal patrols. But the Canadian government didn’t own any military aircraft nor could the British spare any. Canada’s navy had only been founded in 1910 and its main efforts were directed to ship procurement rather than naval aviation. At the time, Canada had no air force.

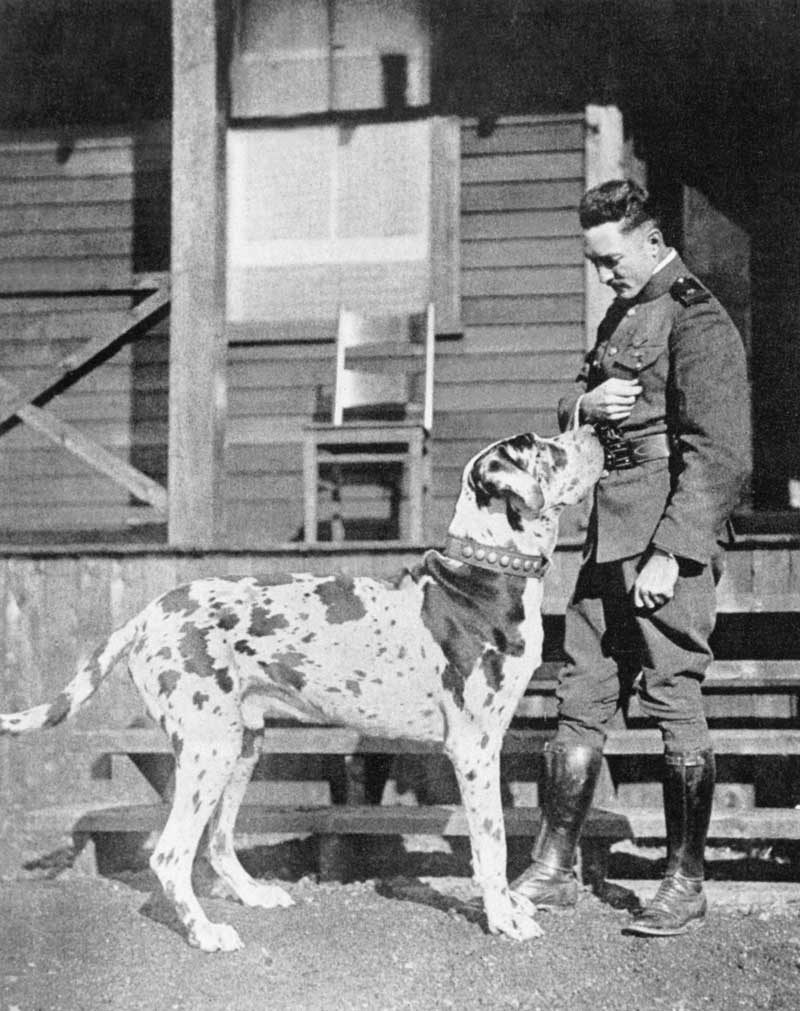

The base was overseen by Acting Lieutenant-Commander (N) Richard Byrd, pictured here with its Great Dane mascot[Shearwater Aviation Museum]

A year earlier, after several American ships were sunk in February and March—coupled with the infamous Zimmermann Telegram (that promised Mexico the return of southwestern states lost during the Mexican-American War of 1846-48 if it joined Germany against the U.S.)—the Americans had declared war on Germany on April 6.

With the U.S. now in the conflict, a conference was held in Washington in the spring of 1918 with representatives of the RN, RCN and USN to discuss air patrols over Canadian coastal waters. It resulted in a comprehensive plan to establish air stations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.

Halifax and Sydney received top priority—each station would have six seaplanes, three dirigibles and four kite balloons (permanently tethered dirigibles). The specific locations were Baker’s Point in Eastern Passage and Kelly Beach in North Sydney. To augment air patrols, the U.S. also provided six submarine chasers, two torpedo boats and a submarine.

The Americans would provide equipment and pilots until Canadians were trained (in the U.S.) and equipped to take over. The creation of the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service, previously rejected by the government, was now approved. Recruiting for the new 500-man service began on Aug. 8.

At this time, U.S. Lieutenant (N) Richard “Dickie” Byrd entered the picture. Byrd, a naval aviator, was anxious to get to Europe and into the war. He had thoroughly studied the new field of flying and was an expert.

When Byrd received orders to report to Washington he was overjoyed, confident the navy had approved his proposal to fly a giant new seaplane to Europe. But when he got there, Byrd was told instead to report to Halifax to command a USN Air Station.

Only the station didn’t exist; he would have to build it. Byrd would be responsible for keeping German subs clear of the coast and escorting convoys in and out of Halifax and Sydney.

In early August 1918, now Acting Lieutenant-Commander Byrd arrived in Halifax with several boxcar loads of equipment. He and his men floated the wingless bodies of their Curtiss HS-2L seaplanes across the harbour to Baker’s Point, where they were reassembled.

A Curtiss HS-2L flying boat launches at Baker’s Point in 1918.[Shearwater Aviation Museum]

The Curtiss connection

Members of the Aerial Experiment Association gather in 1909.[Wikimedia]

Pioneering American aviator Glenn Curtiss joined the newly formed Aerial Experiment Association at Baddeck, N.S., in 1907 at the invitation of Alexander Graham Bell. The next year, flying an association aircraft, he won the Scientific American Aeronautical Trophy for the first flight of at least one kilometre. Curtiss later became the father of naval aviation by developing the world’s first flying boat in 1912 and designed several others, including the HS-2L.

It was a general reconnaissance and patrol aircraft designed by Curtiss in 1917 for the U.S. Navy. It was crewed by a pilot and observer and was powered by a 360-horsepower Liberty liquid-cooled V-12 piston engine. The HS-2L had a range of 830 kilometres with a service ceiling of 2,800 metres. Its cruising speed was 105 kilometres per hour, with a maximum speed of 137. After the war, the HS-2L became Canada’s first bush aircraft and established the traditions of bush flying in the country.

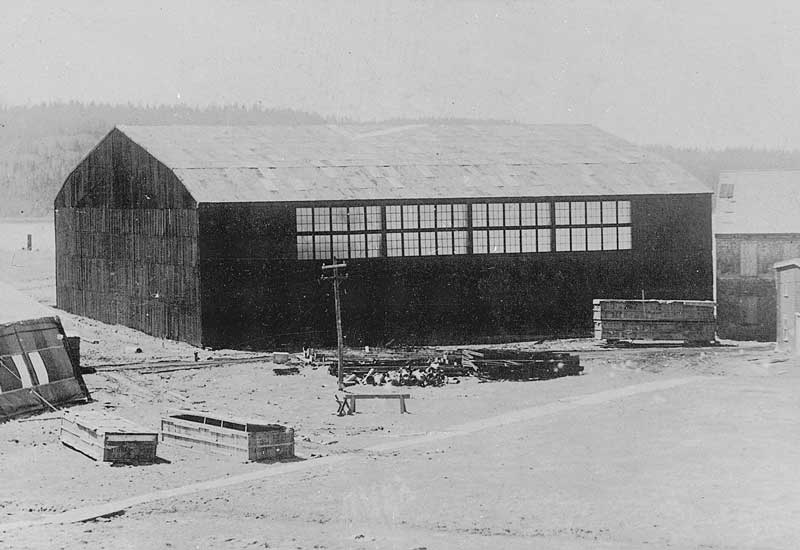

A “bare plot of ground” at Baker’s Point was quickly transformed into “a hustling camp,” including a temporary steel seaplane shelter, known as “Y” hangar. On Aug. 19, the hoisting of the Stars and Stripes signalled the commissioning of Byrd’s command as Officer-in-Charge, U.S. Naval Air Force in Canada.

Byrd’s patrol plans for each site detailed two aircraft for convoy escorts, one for emergency anti-submarine operations and one in reserve. Patrols from Baker’s Point started immediately, but construction delays postponed the North Sydney ones until late September. The two stations quickly established an impressive log of flying hours in convoy protection, spotting for harbour defence guns and coastal surveillance.

Although Byrd’s aircraft did not spot any German U-boats operating in the northwestern Atlantic, the pilots got plenty of practice in marginal flying conditions. According to Byrd, “The highlands and cliffs of Nova Scotia made the air rough and the fog kept it thick. Changes were sudden and violent.”

A temporary steel seaplane shelter, known as “Y” hangar, was one of the first buildings constructed on the Baker’s Point site [Shearwater Aviation Museum]

With the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, Byrd was ordered to return to Washington. He was happy the bloodshed of war was finally over, but bitterly disappointed he had failed to achieve his personal goal of bridging the Atlantic by air.

Despite these frustrations, Byrd enjoyed his relations with Canadians. “Never could any people in the world be more tolerant, helpful, cordial and hospitable than were our Canadian neighbours,” he said. “It was there I learned the great truth that knowledge makes for understanding and tolerance.”

The Fate of Baker’s Point

Today, the original base location forms part of 12 Wing Shearwater. [Shearwater Aviation Museum]

When the Americans departed Nova Scotia, they left aircraft, equipment and the temporary hangar to be taken over by the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service, a force that was disbanded shortly afterward, in December 1918. The airbase at Baker’s Point remained dormant until it became the first east coast station of the new Canadian Air Force in 1920.

Today, Baker’s Point forms part of 12 Wing Shearwater, the centre of naval aviation in Canada. Byrd’s “temporary” Y hangar is now an historic site and is used by Fleet Diving Unit (Atlantic). In 1995, the Admiral Richard E. Byrd Building was opened by Byrd’s daughter as the new base headquarters.

Advertisement