Before Canadian-born movie director James Cameron (Avatar, Titanic) there was James Freer, Canada’s first filmmaker. Born in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England, Freer moved to Manitoba in 1888, settling on a farm near Brandon, some 200 kilometres west of Winnipeg.

Wishing to attract immigrants to the Prairies, Canadian Pacific Railway augmented advertisements.[Wikimedia]

He bought an Edison camera and projector and began making films. The Prairies were still relatively unpopulated and drama was hard to come by. So, Freer shot what was at hand: thousands of hectares of farmland that had the occasional train passing through.

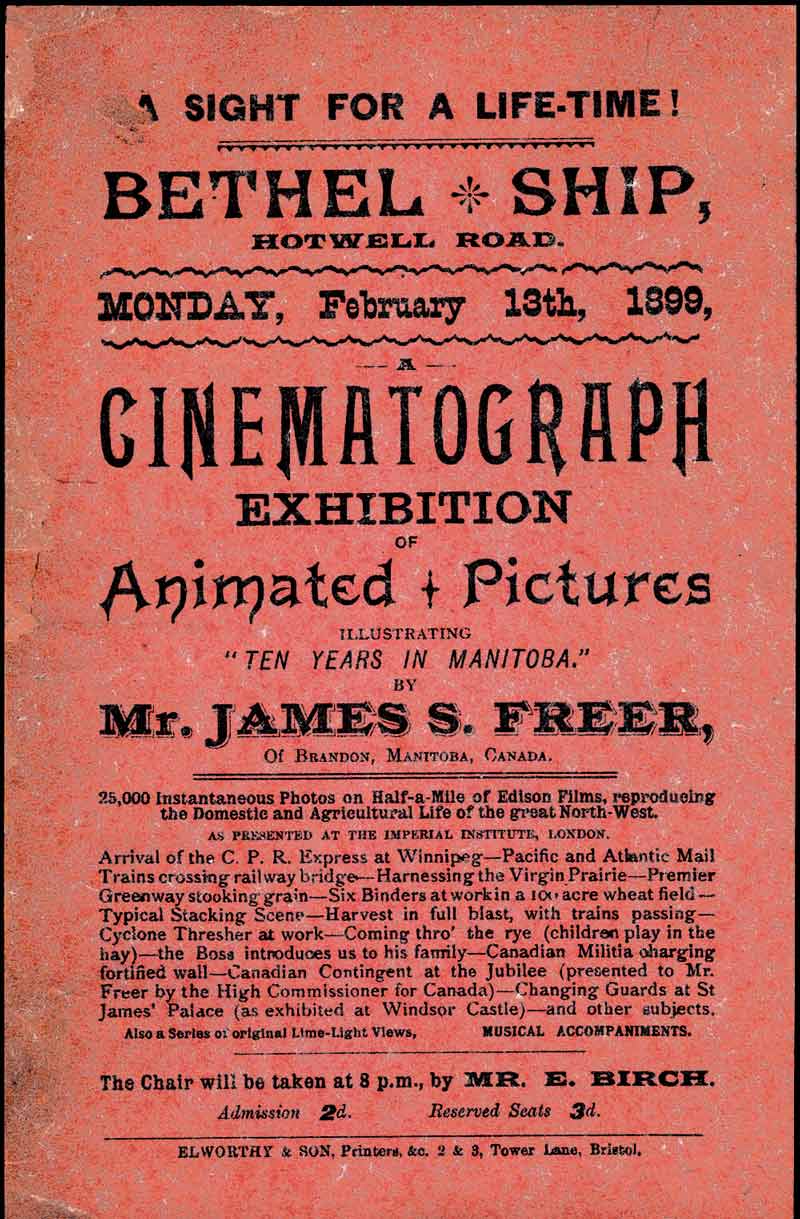

Freer’s 1897 movie Ten Years in Manitoba consisted of short scenes introduced with titles such as: “Harvesting Scene, with Trains Passing By;” “Six Binders at Work in Hundred Acre Wheatfield;” “Pacific and Atlantic Mail Trains;” and “Arrival of the CPR Express at Winnipeg.” There was footage of Freer and his family, too, as well as shots of Thomas Greenway, the Manitoba premier, stooking grain on his own farm.

Ten Years in Manitoba might have had trouble competing with, say, Top Gun: Maverick, but at the time, there wasn’t much in the way of competition. And the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) had only been completed in 1885 and was still a novelty, as was film itself. People flocked to Freer’s flick.

The country’s first film produced the first film controversy when Freer was accused of using other people’s footage. A Winnipeg bartender, an American producer and an entertainment editor all claimed they had been showing Kinetographs that included, among other things, the scene of Greenway stooking his grain that appeared in Freer’s movie.

James Freer’s film Ten Years in Manitoba, promoted on this flyer.[LAC]

There wasn’t much action in Freer’s film, but it contained something alluring: a sense of possibility.

Nevertheless, in 1898, the CPR sponsored a tour through Great Britain where Freer showed his film and delivered lectures. Posters appeared, advertising “animated pictures.” The CPR wanted to attract more immigrants to the Prairies and hoped Freer’s movie would help. Ten Years in Manitoba was a surprise hit, drawing audiences throughout the U.K.

There wasn’t much action in Freer’s film, but it contained something that was almost as alluring: a sense of possibility. The sheer scale of Manitoba, with its endless space and wide prairie skies held broad appeal for foreign audiences. England was still a largely agrarian society, and this was farm life on steroids.

In 1902, a second tour of the U.K. was arranged for Freer and his film, this one sponsored by the federal government. Clifford Sifton, the minister of the interior, also wanted to populate the Prairies. He had already sent a million pamphlets around the world extolling the virtues of farm life in Canada—they were a bit misleading, claiming, for instance, that “The Frontier of Manitoba is about the same latitude as Paris”—but they didn’t bring in the numbers Sifton had hoped for. He particularly wanted British farmers and thought an encore of Freer’s earlier trip could help.

This one wasn’t as successful, however. Some of the Brits who had seen Freer’s film four years earlier had actually emigrated, and reported back that Freer had neglected to mention the long, harsh winters and the plague of summer mosquitoes.

The failure of this tour effectively ended Freer’s film career. He returned to his original profession of newspaperman, working for the Manitoba Free Press.

Advertisement