Lieutenant-General Eedson L.M. (Tommy) Burns takes in the Italian landscape in September 1944. [DND/LAC/PA-171701]

“Things have reached a crisis here,” Major-General Christopher Vokes wrote a friend in England on Nov. 2, 1944. “Personally I am absolutely browned off. In spite of no able direction we have continued to bear the cross…. I’ve done my best to be loyal but goddamnit the strain has been too bloody great.”

Vokes was the general officer commanding of the 1st Canadian Division in Italy, and the subject of his ire was the commander of I Canadian Corps, Lieutenant-General Eedson L.M. Burns. Relations between Burns and his key subordinates had reached the breaking point, and Burns, soon relieved of command and reduced in rank to major-general, was posted to rear area duties in Northwest Europe. How had matters reached this point?

Burns was 47 years old in 1944. Born in Montreal, he had attended Lower Canada College and entered the Royal Military College in August 1914 where he picked up the nickname Tommy, after the famed Canadian world heavyweight boxing champion of the time.

He received the nickname, after the famed boxer, while attending the Royal Military College.[Royal Military College of Canada Museum/Wikimedia]

He did well academically in his first and only year at the college, but took a wartime commission in the Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE) as soon as he turned 18 in June 1915 and trained as a signals officer. He went to England with the 4th Division in August 1916, then to France.

Wounded twice, he was awarded the Military Cross for laying and repairing signal cables under heavy fire. By the end of the war, Burns was a staff captain attached to the 12th Infantry Brigade under its acting commander, Colonel J. Layton Ralston. “They say he looks more like 35 than 21,” his mother wrote to the commandant of the military college in 1919, an indication that Burns’ war experiences had weighed heavily.

A young Burns poses with his father [CWM/19850427-016]

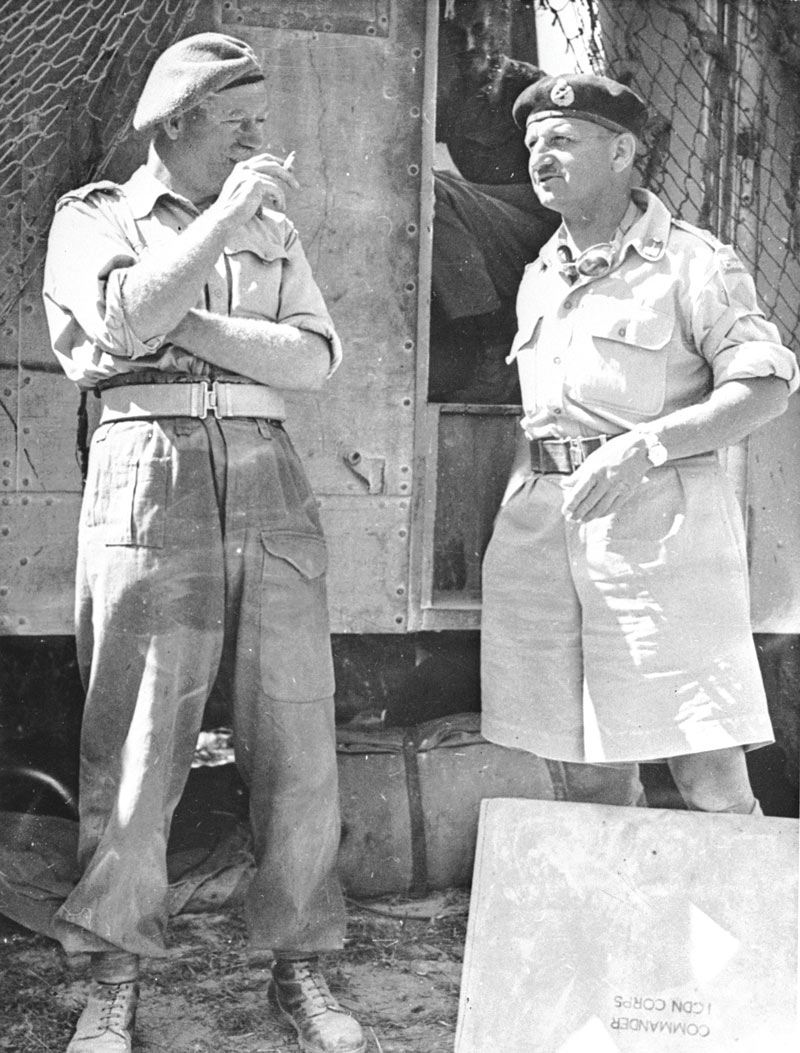

Later, he took command of I Canadian Corps in Italy (opposite right) in March 1944 from Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar.[C.E. Nye/DND/LAC/ PA-134178]

Burns nonetheless stayed in the army, joining the tiny Permanent Force as a captain in the RCE. Quickly recognized as a comer, Burns became a major in 1927 and took the examinations for staff college, scoring the top mark among the Empire-wide applicants. He went to the British Army Staff College in Quetta, India (now Pakistan) in 1928-29. He was deemed “a very popular officer” with “a great sense of humour,” a “strong and imperturbable” character and an “ability to express himself well on paper.” Few others, however, would see a great sense of humour in Burns.

On his return home, he soon worked for Colonel Harry Crerar at National Defence Headquarters where he devised new methods of aerial photography that mapped much of Canada, and for which he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1935. Promotion was glacial in the interwar army, but Burns was on the fast track.

Tommy Burns was not only a soldier. As his Staff College assessment had noted, he expressed himself well on paper. In the 1920s, under the pseudonym Arlington B. Conway, he wrote articles on the military for Henry L. Mencken’s The American Mercury magazine.

Mencken was a sharp critic of American life, and Burns’ sardonic, cutting pieces fit right in. He attacked soldiers who believed that trench warfare hadn’t minimized the value of cavalry. “The smell of the stables is an incense to their nostrils,” he wrote. “They look on the horse as a romantic symbol of personal superiority.”

Another article noted that it was impossible to develop initiative in infantrymen: “if the ranks of the infantry were filled with intelligent men, it is unlikely that they would long submit willingly to being used as it is intended to use infantry.”

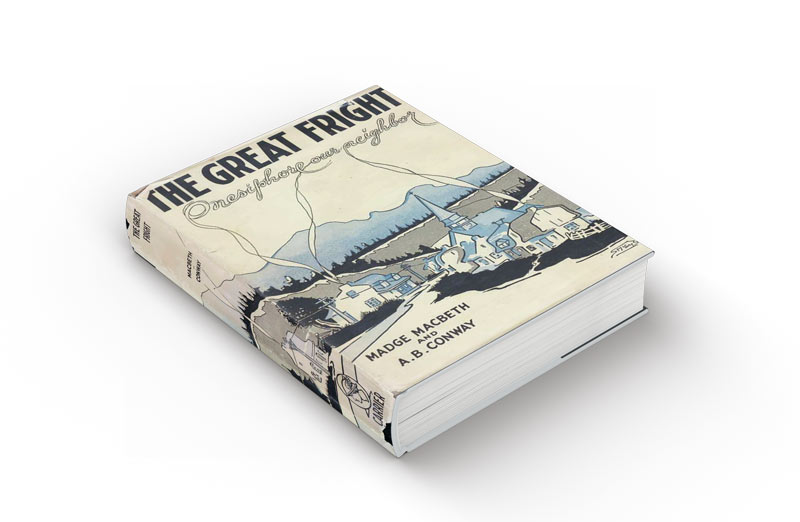

In 1929, Burns co-wrote a novel under the pseudonym A.B. Conway.[AbeBooks.com]

Burns’ writing was not limited to military subjects. He wrote short stories, a play and even a novel with Madge Macbeth, a well-known Ottawa writer. The Great Fright: Onesiphore Our Neighbor was published in 1929. The book, a part written in a mock habitant prose that was out of fashion, attracted little notice. Using a pseudonym, Burns had hoped he would stay anonymous. Nonetheless, advertising for the novel used his photograph and name, but none in National Defence Headquarters noticed. Neither did reviewers or readers.

Burns also frequently wrote articles and reviews for Canadian Defence Quarterly, the military’s semi-official journal. Posted to Montreal in a senior staff role in 1938, he published an article on the use of tanks in battle that drew a spirited response from Captain Guy Simonds, another officer on the rise.

Burns called for a division to be made up of one armoured and two infantry brigades. Simonds argued that armour should be kept in reserve, not decentralized, and used when needed for a major attack. Their exchanges continued and were arguably the high point of interwar military thinking in Canada.

Soon after the first of these articles appeared, Burns was in England attending the Imperial Defence College, the route to high command. The coming war interrupted his course, and Burns moved to the Canadian High Commission, assisting future Governor General Vincent Massey and future Prime Minister Lester Pearson with military matters until Crerar, now a brigadier, arrived to set up the Canadian Military Headquarters in Britain.

As his principal staff officer, Burns did the heavy lifting, and Crerar soon had him promoted to colonel and took him back to Canada when he became chief of the general staff. Again, Burns’ workload was massive, and he had arguments with Ralston, now defence minister. Ralston told one of his confidants that Burns and another staff officer were “as stupid as wooden Indians.”

That comment, however, did not dissuade Crerar who made Burns responsible for organizing the development of the army’s new armoured units, and Burns was frequently in Montreal overseeing the development of the Ram tank. Soon, he returned to England as brigadier general staff of the Canadian Corps under Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton, who was also satisfied with his work.

Down but never out,Tommy Burns managed to overcome his personality defects and achievedgreat success.

Later, he took command of I Canadian Corps in Italy (opposite right) in March 1944 from Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar. [LAC/4232973]

Two key Canadian wartime generals supported Burns, but his rise was disrupted when a letter he wrote was intercepted by military censors.

During his time in Montreal, Burns had had an extramarital affair. Short, pudgy and not particularly handsome, Burns nonetheless was substantially successful at seduction. But this missive to his mistress, while full of sappy love talk, also commented on politicians, war strategy and British generals, as well as referring to McNaughton’s opinions of a particular senior officer.

Burns was lucky to escape a court martial, but he was returned to Canada, sharply rebuked by Crerar and Ralston, and busted to colonel. Still, he was named officer administering of the Canadian Armoured Corps, a post that required frequent visits to Montreal—and his girlfriend.

Generals of the 1st Canadian Army, including Burns (second row, fifth from right), sit for a group portrait in May 1945. [K. Bell/DND/LAC/PA-138509]

Promoted to brigadier in early 1942, Burns took command of an armoured brigade in the still-forming 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division. He went with it to England in October.

Burns returned to England as brigadier general staff of the Canadian Corps under Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton.

His full redemption came in May 1943 when Burns, on the recommendations of Crerar and McNaughton, became a major-general and commander of 2nd Canadian Division. It was a difficult assignment as the division had been shattered in the abortive Dieppe Raid the previous August. In his nine-month stint in command, Burns made progress in rebuilding the division.

Favoured as he was by his superiors, not everyone was impressed with Burns. In mid-1943, one of Ralston’s advisors wrote appraisals of senior officers overseas and was unflattering in his review of Burns.

“Exceptionally high qualifications but not a leader,” said the review. “Difficult man to approach, cold and most sarcastic. Has probably one of the best staff brains in the Army and whilst he will lead his Division successfully he would give greater service as a high staff officer.”

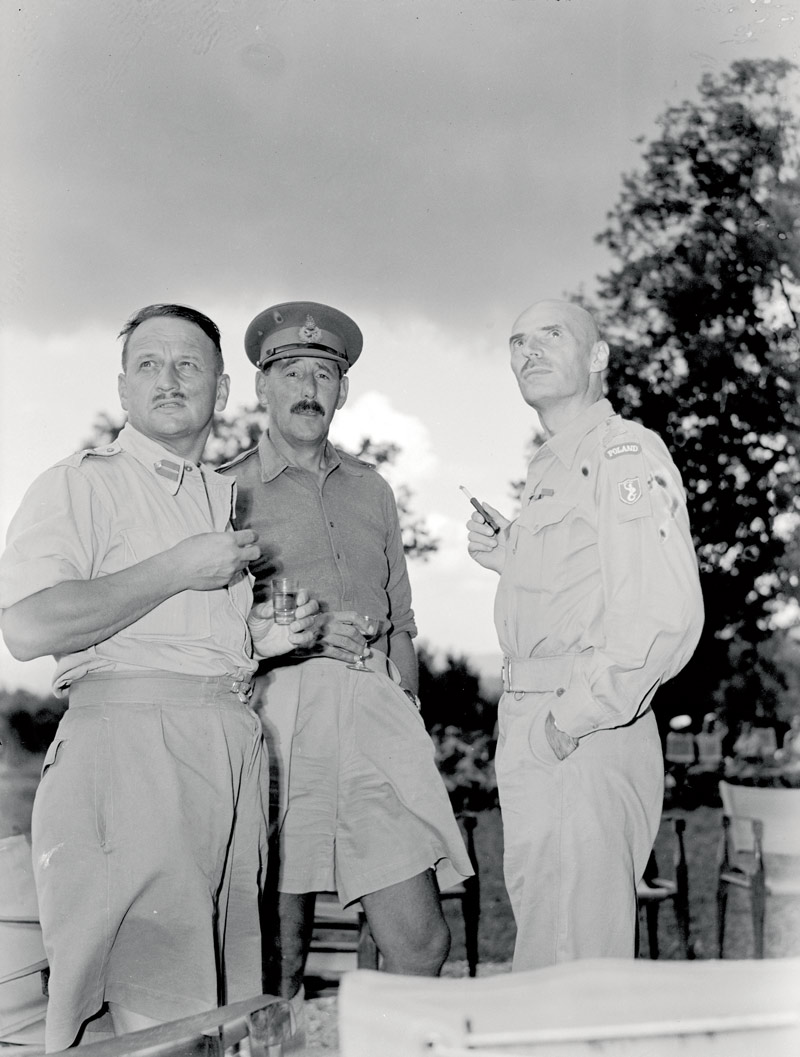

Burns poses with British Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese and Polish Lieutenant-General Wladyslaw Anders and again with Major-General Christopher Vokes in Italy opposite bottom [LAC/3718084;]

Burns poses with British Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese and Polish Lieutenant-General Wladyslaw Anders and again with Major-General Christopher Vokes in Italy opposite bottom [LAC/PA-185006]

That was exactly right.

In late 1943, Crerar took command of I Canadian Corps in Italy, and in January 1944, Burns became general officer commanding of the 5th Canadian (Armoured) Division, replacing Guy Simonds, who returned to Britain to command II Canadian Corps. Soon to replace McNaughton in Britain, Crerar wrote that “if Burns acts up to expectations he will undoubtedly be my recommendation for Corps Commander.”

Burns again had little time in his new post, certainly not enough to acquire experience in action. The British believed that first-hand battle knowledge was key—and six weeks in command of the 5th was not enough time to get it. Burns nonetheless became Corps commander and acting lieutenant-general on March 20, 1944.

Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese, commander of the Eighth Army, was not pleased to have the untried I Canadian Corps in his group. He initially thought Burns satisfactory, but after the battle in May to crack the Hitler Line in Italy, he changed his mind. While the Canadian divisions had fought well, there were huge traffic jams that delayed the advance. Leese blamed Bert Hoffmeister’s 5th Division and Burns’ staff. He tried to have Burns replaced, ideally with a British general.

“Neither Burns nor his Corps staff are up to Eighth Army standards,” wrote Leese. Still, Crerar remained a strong supporter and, after much palaver, Burns retained his position by replacing some of his staff. His division commanders, Vokes and Hoffmeister, were at first willing to continue to work with him, but by the autumn they had changed their minds.

Burns’ Corps had cracked the Gothic Line in Italy at the end of August 1944, arguably the most successful Canadian action of the war. But, his British superiors, his two division commanders and some of the Corps’ senior staff officers had had it with him. Still, Crerar again tried to save Burns.

No one, however, could remember Burns smiling—the troops called him “Smiling Sunray” in derision—and he could not inspire his subordinates. He was a sarcastic, dour personality who seemed to only criticize. Burns, said Vokes, “lacks one iota of personality, appreciation of effort or the first goddamn thing in the application of book learning to what is practical in war & what isn’t.”

Hoffmeister, meanwhile called the relationship intolerable and said he had lost all confidence in Burns. Burns had won major battles in the field, but his personality defects did him in. As Ralston’s confidant had presciently written a year earlier, Burns “will never secure devotion of his followers.”

His hand forced, Crerar replaced Burns with Charles Foulkes on Nov. 10.

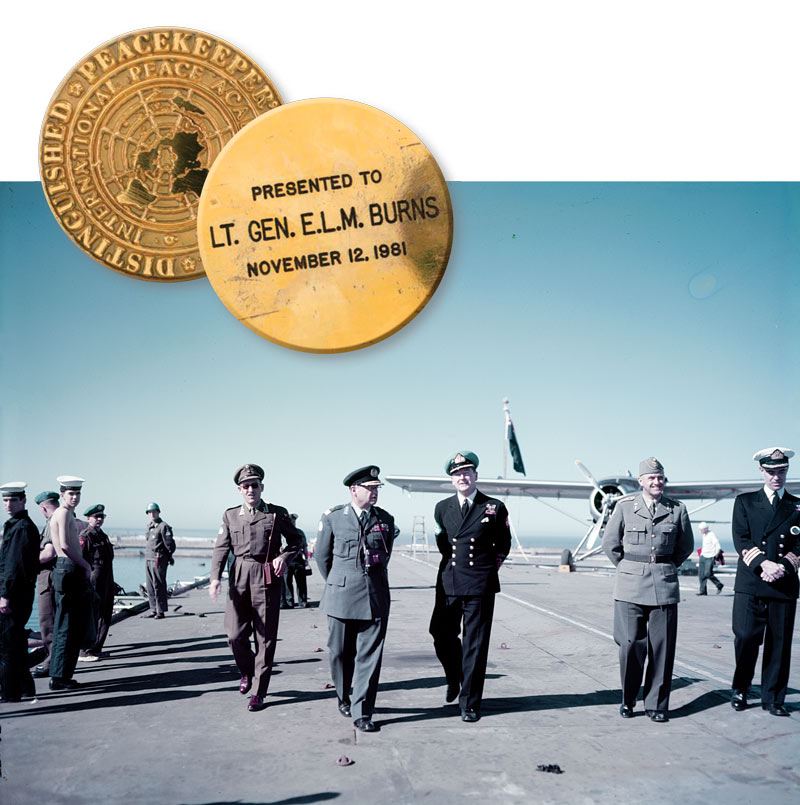

In the aftermath of the Suez Crisis, Burns (left) visits HMCS Magnificent in 1957 while in command of the UN Emergency Force. He received the Distinguished Peacekeeper’s Award for that work.[DND/LAC/4951082]

Burns spent the rest of the war in minor posts in Northwest Europe. After the conflict, he joined the Department of Veterans Affairs, eventually becoming its deputy minister. He wrote a fine study of Canada’s military workforce problems during the war and, in 1954, he was named to head the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization on the Arab-Israeli borders. Burns was in that job during the 1956 Suez Crisis and, on the spot, was given command of the UN Emergency Force, the first large peacekeeping operation.

When the Egyptians objected to accepting Canadian infantry in the UN force because they were indistinguishable from the invading British—they wore the same uniforms, their regimental names were redolent of the Empire and their flag had the Union Jack in the corner—Burns persuaded Cairo to let Ottawa provide logistics and signals personnel instead.

That move was much appreciated by the federal government and in 1958 Burns was promoted to lieutenant-general. Two years later, he was made the government’s disarmament adviser. Burns died in 1985, his sacking in 1944 almost forgotten.

Down but never out, Tommy Burns managed to overcome his personality defects and achieved great success. He had served in the Great War with distinction, advanced through the Permanent Force in the interwar years, and served in high command during the Second World War. His postwar career and life were extraordinary. If he was cold and critical, his intelligence and drive shone through nonetheless.

Advertisement