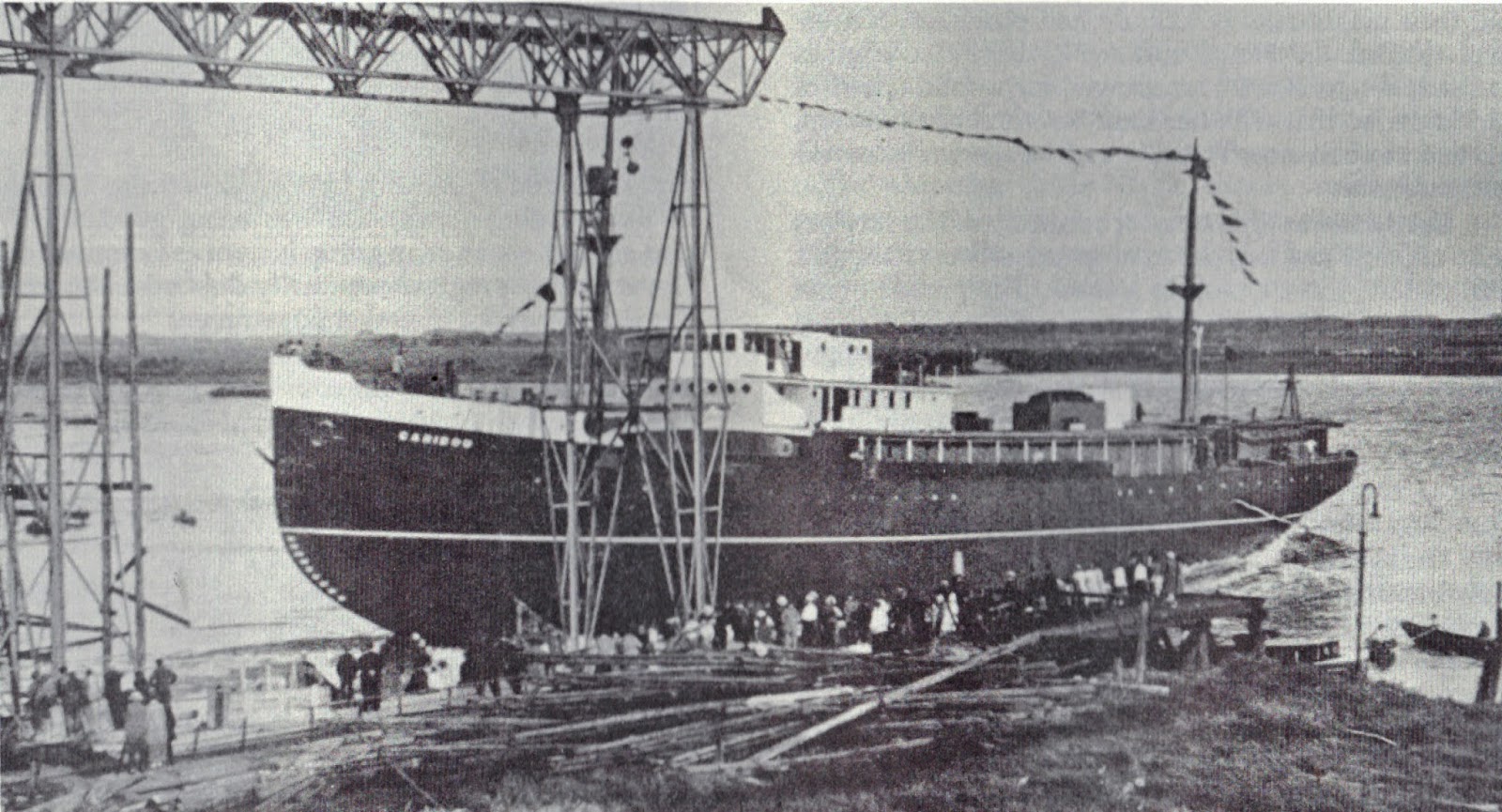

SS Caribou in drydock. The ferry was built by Goodwin–Hamilton S. Adams Ltd. of Rotterdam and was launched in June 1925. [Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland]

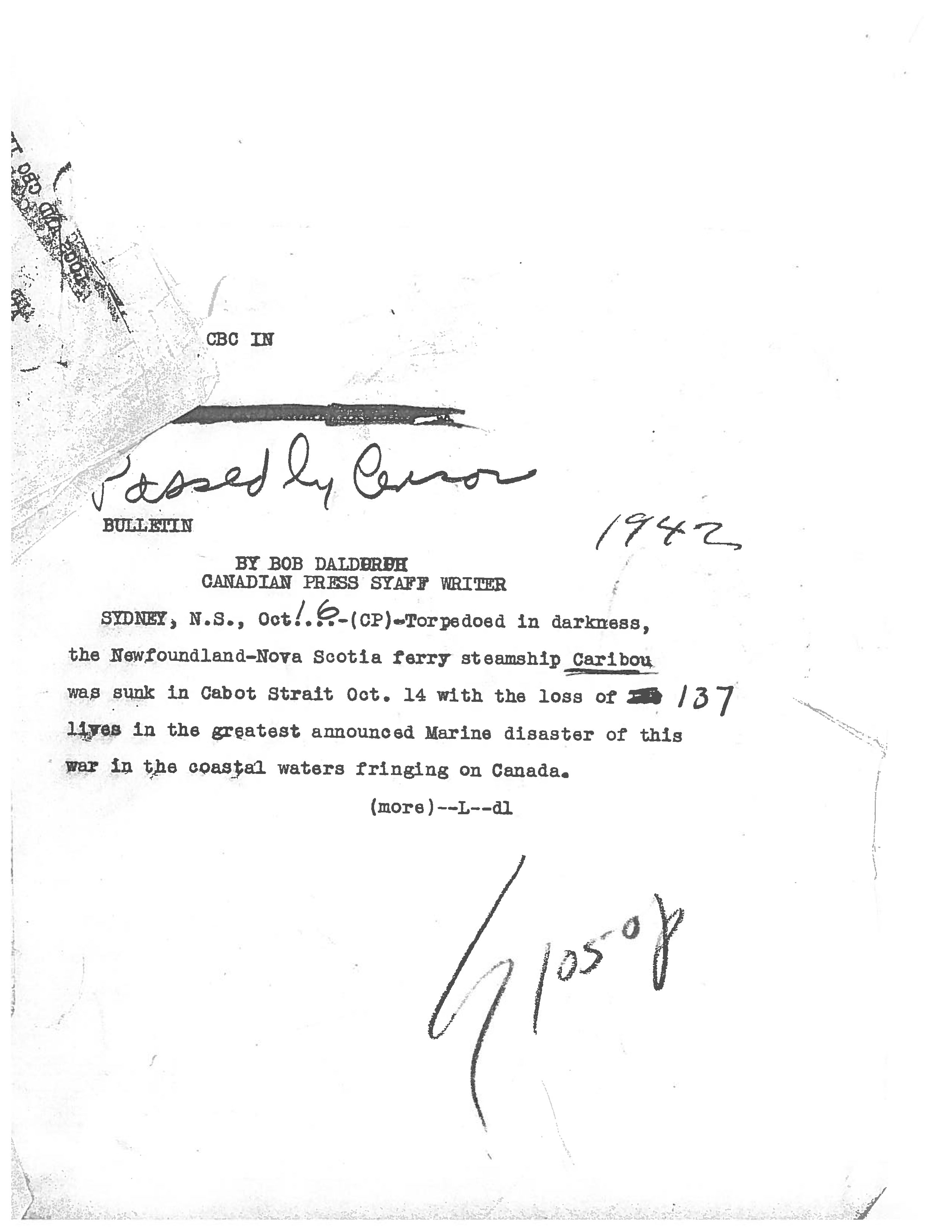

The original sat in a musty filing cabinet in the Halifax office of The Canadian Press for years: a sheaf of rice paper, its first page scrawled with the words “Passed by Censor 1942” across the top, just above the typed “BULLETIN.”

It was dated Oct. 16 out of Sydney, N.S., the first news report of the sinking of the SS Caribou two days earlier at the hands of a German U-boat, U-69. The file had long since disappeared when I left CP in 2012.

Recently, however, I found a photocopy I had made for posterity because the report, with its editor’s markups and censor’s redactions, is quite a remarkable piece of history, despite the fact it appears to be incomplete.

To many Canadians and Newfoundlanders alike, the sinking and the deaths of 137 people were the clearest sign to date that the war had actually arrived on the home front. Many historians cite it as Canada’s most significant sinking in near-shore waters of the Second World War.

Written by Canadian Press staff writer Bob Daldorph in an age when agency news was actually disseminated by telephone cables (or wires—hence, the wire service), the story was sent in bite-sized takes, the first of which is the single-sentence bulletin sent at 10:50 p.m.

Click above: The original Canadian Press wire story on the sinking of the SS Caribou. Written by CP staff writer Bob Daldorph, it was held up by censors for two days. It was transmitted in takes, beginning with a one-paragraph bulletin.

With existing typos included and editors’ corrections, inserts or updated numbers (made with grease pencil) in boldface, the bulletin reported:

LOCS AND CBC IN

BULLETIN

SYDNEY, N.S. Oct. 16 (CP)—Torpedoed in darkness, the Newfoundland-Nova Scotia ferry steamship Caribou was sunk in Cabot Strait Oct. 14 with the loss of 137 lives in the greatest announced Marine disaster of this war in the coastal waters fringing on Canada.

(more)

The day of transmission, the 16th, is penciled in because the typist didn’t know how long the story would be held up by censors, and the number of dead was updated by the time the piece moved.

That it moved at all was unusual at that time. The Royal Canadian Navy apparently allowed media to report the sinking in order to stymie the rumour mill.

Bulletins are second in the wire service’s priority list, just behind the headline-reading “flash” and before the lesser, and more detailed, “urgent.” A bulletin would prioritize the story in the queue—moving it up, say, from fifth in line to second, behind the story that was actually printing at the time it was transmitted—and it would trigger bells on a newsroom’s printer. A flash would interrupt incoming copy, taking precedence over all and triggering more bells.

The story’s first add continues:

Canadian naval craft saved 101 passengers and crewmen after the 2,200-ton vessel, owned by the Newfoundland government, had been sent to the bottom by a submarine that surfaced after the kill and watched the finish of the Caribou and the struggles of her survivors in the pre-dawn gloom.

Struck as she neared the end of her overnight run from North Sydney, N.S., to Port aux Basques, Nfld., the vessel sank within a few minutes. Servicemen and civilians—men, women and children—from canada, newfoundland, and the united states perished as the shattered caribou carried down scores of persons who were asleep in their staterooms when the explosion tore the ship apart.

SIXTY-EIGHT Canadians—49 of them servicemen—were lost. EIGHTEEN were civilian passengers; one was a member of the crew; twenty were members of the royal Canadian navy [AND ROYAL NAVY]; 18 were in the royal canadian air force, and the remaining 11 were army men.

(more)

Newfoundland was, of course, still a dominion of Great Britain at the time. It would not join Confederation until after a referendum in 1949.

Caribou was sailing under escort, part of the three-times-weekly Sydney-Port aux Basques run that always took place after dark. HMCS Grandmère, a Bangor-class minesweeper, provided the coverage.

The heavy smoke from Caribou’s coal-fired steam boilers silhouetted the tidy little ship against the horizon, making it easy prey for U-69 as it patrolled the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. The ship was torpedoed at 3:51 a.m. Newfoundland Summer Time about 37 kilometres southwest of Port aux Basques. It sank five minutes later.

Those details could not be reported at the time:

Out of a crew of 46—mostly newfoundlanders—31 went down. Another eight of the victims consisted of united states service personnel, and there were FIVE U.S. civilians. The remaining 26 victims were Newfoundland civilians on the passenger list.

Captain Benjamin Taverner of Channel, Nfld., master of the 16-year-old one-time sealing vessel, went down with his ship. And with him were lost two of his sons, both officers of the vessel.

The survivors, who were landed here the day of the sinking, told how Capt. Taverner steered his settling craft at the boldly-surfaced submarine after the hit, apparently in an effort to ram the attacker. But the Caribou slid under before she could get her icebreaker’s prow against the hull of the U-boat.

The ever-cautious censor scratched out the following paragraph:

Racing Canadian naval ships and r.c.a.f. planes quickly forced the marauder under the surface. There was no disclosure of the result of their attack.

(more)

The torpedo attack occurred nine months after the Kriegsmarine launched Operation Drumbeat, a U-boat offensive off the eastern seaboard that left a trail of post-Pearl Harbor destruction all the way down to the Florida coast.

The first stage of the Battle of the Saint Lawrence was coming to a close. For five months in 1942, again in September 1943, and in October and November 1944, U-boats sank 23 ships, including four Canadian warships, while patrolling throughout the lower Saint Lawrence River, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, the Strait of Belle Isle, Anticosti Island and the Cabot Strait.

U-190 arrives in St. John’s in June 1945 after surrendering to Royal Canadian Navy sailors off the coast of Newfoundland on May 12, 1945. [LAC/PA-145584]

The first two paragraphs of the third add to Daldorph’s story never saw the light of day, struck off by the censor’s grease pencil:

Later, after the sub had slipped under the surface, she was attacked heavily by ships of the canadian navy that raced up to the scene. With the area lit by flares, the survivors watched from their lifeboats and from the water as the warcraft tossed a bombardment of depth charges after the sub.

Those rescued said about 20 depth charges were loosed. The was NO word from the navy on the results of the attack.

The uncensored part of the story continued:

Apart from the death loosed by her torpedo, the submarine herself was believed to have contributed to the loss of life. Some survivors said that as she broke the surface the hull of the U-boat capsized one or two rafts and smashed a lifeboat, and they believed some of those on the rafts and boat were lost.

The capsizing of another lifeboat apparently sent around 40 persons to death. George Smothers of Toledo, O., a U.S. navy cook, said the boat originally carried about 50 persons but only six aboard it were left after it had rolled over several times.

One woman in it managed to cling to her baby throughout the hours of ordeal.

(more)

Despite the onslaught, U-69 slipped away into the North Atlantic undetected. Five days earlier, it had sunk the Canadian merchant ship SS Carolus in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence near Bic Island. Eleven merchant crew were lost. The ship’s master William Broman, 16 crew and two gunners were picked up by HMCS Hepatica.

U-69 was the first Type VIIC unterseeboot commissioned, in 1940. It was skippered by Kapitänleutnant Ulrich Gräf, its fourth and last commander. The sub sank 17 Allied ships over the course of its service, totaling 67,515 gross tonnes, and damaged two more, one of them a total loss.

Caribou would be its last kill. Uboat.net reports U-69 was sunk with all hands on Feb. 17, 1943, in the North Atlantic east of Newfoundland by depth charges from HMS Fame. Other reports suggest the British destroyer rammed the German sub.

Its efforts to avenge the Caribou frustrated, Grandmère returned to the scene of the sinking to recover survivors. Newspapers would criticize the navy ship in the following days for not immediately coming to the aid of those in the water. But the vessel was following strict procedure; to do otherwise would have put Grandmère and its crew at risk of following Caribou to the bottom.

HMCS Grandmère, a Bangor-class minesweeper, was escorting Caribou the night the ferry was torpedoed. [Wikimedia]

It was between three and five hours before all the survivors were picked up, because of the darkness and the fact the arriving naval craft were busy tracking down the submarine. The survivors, some of them with only bits of flotsam to cling to, waited in water that chilled to the bone.

Sub-lieutenants Margaret Brooke and Agnes Wilkie, RCN nursing sisters aboard Caribou, had clung to ropes on an overturned lifeboat until Wilkie passed out from hypothermia. Brooke held the rope with one hand and her unconscious friend with the other until daybreak when, despite her best efforts, a wave pulled Wilkie away.

Brooke was later named a Member of the Order of the British Empire and, in 2015, the Harry DeWolf-class offshore patrol vessel HMCS Margaret Brooke was named in her honour.

Grandmère sailed for Sydney, a longer haul than Port aux Basques, but the Cape Breton city had better hospital facilities.

The modern-day ferry MV Caribou was named for SS Caribou in 1986, plying the same North Sydney-Port aux Basques route as its predecessor. On its maiden voyage, the ship paused at the site of the sinking and Mack Piercey, one of 13 survivors on board, dropped a poppy-laden memorial wreath into the ocean.

Advertisement