An artist’s impression from The Illustrated London News of Jan.9, 1915, “British and German Soldiers Arm-in-Arm Exchanging Headgear: A Christmas Truce between Opposing Trenches.” [Wikimedia]

It was Christmas Eve 1914. The Tommies of Britain’s Queen’s Westminster Regiment had returned to the frigid trenches the previous day, relieving regular troops after four days of rest.

Suddenly, in the stillness and cold, the voice of a young farmer’s son, Edgar Aplin, rose up from the frozen earth with “Tommy, Lad!,” a popular song written in 1907 by American lyricist Edward Teschemacher and composer E.J. Margetson:

Tommy, lad! Tommy, lad!

Though you’re scarce a wee year old;

Yet you’re long and you’re strong,

And your head’s a mass of gold;

And you’ve got a mighty will of your own,

You’ve got a kind of way,

That will carry you along, I know;

When you face the world one day,

Tommy lad!

A few hundred metres away, from the opposing trenches where the 107th Saxon Regiment was dug in, voices called out: “Sing it again, Englander. Sing ‘Tommy, Lad!’ again.”

And so he did. And as the London Telegraph described it, thus began “one of the most remarkable episodes ever to take place in the history of armed conflict.”

In a letter home, unearthed a century after it was written, Alpin described the chain of events that led to the now legendary Christmas Truce of 1914. Back in July, many had predicted the war would be over by then.“On Christmas Eve, the usual war methods went on all day, sniping, etc., until the evening, when we started a few carols and the old home songs,” he wrote.

“Immediately, our pals over the way began to cheer, and eventually we got shouting across to the Germans. Those opposite our front can mostly speak English.

“Soon after dark, we suggested that if they would send one man halfway between the trenches (300 yards), we would do the same–and both agreed not to fire.

“So, advancing towards each other, each carrying a torch, when they met, they exchanged cigarettes and ‘lit up.’ The cheering on both sides was tremendous, and I shall never forget it. After a little while, several others went out, and a pal of mine met an officer who said that if we did not shoot for 48 hours, they wouldn’t. And they were as good as their word, too. On Christmas Day, we were nearly all out of the trenches. It was almost impossible to describe the day as it appeared to us here and I can tell you, we all enjoyed the peaceful time.”

It wasn’t the only unofficial truce in 1914, the only year of the Great War that there would be any Christmas truce at all.

Troops, including Canadians, in scattered locations all along the front spontaneously, if not cautiously, declared their own truces, emerging from their trenches to exchange food and souvenirs, hold joint burial ceremonies and prisoner swaps, and sing carols. Men also played soccer, creating one of the most enduring images of the short-lived peace.

Alpin would eventually be wounded in the legs, but he survived the war. After it was over, he started a milk round, pushing a cart around the streets of Tonbridge, England. Later, he set up a small chain of tea rooms, called Alpin’s Tudor Cafés.

His 89-year-old son Ian said his father had spoken often of the Christmas truce, which has so far proven unique in the annals of war.

Three decades later, however, in a cabin in a forest just across the Belgian border into Germany, a much smaller but just as improbable truce took place, the details of which read like something out of the Brothers Grimm.

It was the Battle of the Bulge, one of the last German offensives of the Second World War. The paratroopers of the U.S. 101st Airborne were hungry and low on ammunition. Weather was preventing resupply drops.

Nevertheless, Brigadier-General Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st at Bastogne, had two days earlier famously rejected his German counterpart’s surrender terms.

“There is only one possibility to save the encircled U.S.A. troops from total annihilation: that is the honorable surrender of the encircled town,” said a typed note, delivered by four German soldiers and signed “The German Commander.”

He gave McAuliffe two hours to decide.

“If this proposal should be rejected one German Artillery Corps and six heavy A. A. Battalions are ready to annihilate the U.S.A. troops in and near Bastogne.”

McAuliffe’s reply, typed and centered on a full sheet, was simple and direct:

December 22, 1944

To the German Commander,

N U T S!

The American Commander

The weather in the Ardennes broke on Christmas Eve and American resupply drops began immediately. Shown is a resupply drop on Dec. 26, 1944. [Wikimedia]

On Christmas Eve, the day the weather broke and resupply commenced, they stumbled on a small cabin in the woods. Inside, Elisabeth Vincken and her 12-year-old son Fritz had been hoping her husband Hubert would arrive for Christmas. The family home in Aachen, Germany, had been bombed and Hubert, a Wehrmacht baker, had moved them to the relatively secure hunting cabin in the Hurtgen Forest near the Belgian border.

A soldier walks through the forest outside Bastogne, Belgium, on Dec. 27, 1944. [Wikimedia]

Suddenly, there was a knock on the door. Elisabeth opened it and there, standing before her, were two enemy soldiers. A third was prostrate in the snow with a gunshot wound to the leg.

Brigadier-General Anthony McAuliffe and his staff celebrate Christmas in Bastogne, Belgium, on Dec. 25, 1944, while surrounded by German troops. [Wikimedia]

Elisabeth invited them inside and they laid the wounded man on a bed. She and one of the soldiers were able to communicate in French. Eventually, Elisabeth sent Fritz to fetch six potatoes and Hermann the rooster, named for Nazi leader Hermann Göring, for whom she had little time or affection.

Hermann was roasting in the oven when there came another knock on the door. Fritz opened it and was confronted by four German soldiers.

“I was almost paralyzed with fear,” Fritz would later recall, “for though I was a child, I knew that harsh law of war: Anyone giving aid and comfort to the enemy would be shot.”

A terrified Elisabeth pushed past her son, stepped outside and closed the door behind her. The German corporal and three young soldiers were lost and hungry. They politely wished her Fröhliche Weihnachten (Merry Christmas).

Elisabeth told them they were welcome to come into the warmth and eat until the food was gone, but she cautioned that there were others inside whom they would not consider friends.

The corporal asked sharply if her guests were Americans. She related the Americans’ story, so similar to their own, then answered the corporal’s hard stare with the words: “Es ist Heiligabend und hier wird nicht geschossen. (It is the Holy Night and there will be no shooting here).”

A German soldier during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. [Wikimedia Commons]

“There was a lot of fear and tension in the cabin as the Germans and Americans eyed each other warily,” wrote historical blogger David Hunt, “but the warmth and smell of roast Hermann and potatoes began to take the edge off.”

The Germans produced a bottle of wine and a loaf of bread. While Elisabeth tended to the cooking, one of them, an ex-medical student, examined the wounded American. He explained in English that the cold had prevented infection but he had lost a lot of blood. He needed food and rest.

By the time the meal was ready, Hunt reported, the atmosphere was more relaxed.

Two of the Germans—Heinz and Willi—were just 16; the corporal was 23.

“Then Mother said grace,” Fritz would later recall. “I noticed that there were tears in her eyes as she said the old, familiar words, ‘Komm, Herr Jesus. Be our guest.’

“And as I looked around the table, I saw tears, too, in the eyes of the battle-weary soldiers, boys again, some from America, some from Germany, all far from home.”

Later, Elisabeth read from the Bible and, said Fritz, she “declared that there would be at least one night of peace in this war.”

The U.S. 347th Infantry Regiment pauses for a meal in the forest near La Roche, Belgium, on Jan. 13, 1945. [Wikimedia Commons]

The enemies then shook hands, took up their weapons, and left in opposite directions, back to their respective sides and the battle.

Fritz and his parents survived the war. Elisabeth and Hubert Vincken died in the early-1960s. Fritz had married in 1958 and was living in Hawaii, where he operated Fritz’s European Bakery in a Honolulu neighbourhood.

For years, he tried to track down the German and American soldiers without luck.

U.S. President Ronald Reagan referenced the improbable story in a May 6, 1985, speech after an emotional visit to the war cemetery at Bitburg, Germany. It was 40 years since the war had ended and six years before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

“That night, as the storm of war tossed the world, they had their own private armistice,” said Reagan. “Those boys reconciled briefly in the midst of war. Surely, we allies in peacetime should honor the reconciliation of the last 40 years.

“The one lesson of World War II, the one lesson of Nazism, is that freedom must always be stronger than totalitarianism, and that good must always be stronger than evil. The moral measure of our two nations will be found in the resolve we show to preserve liberty, to protect life and to honor and cherish all God’s children.”

Fritz Vincken, who followed in his father’s footsteps and became a baker, though in Hawaii, far from his native Germany. He died at age 69 in Salem, Oregon. [Fritz Vincken]

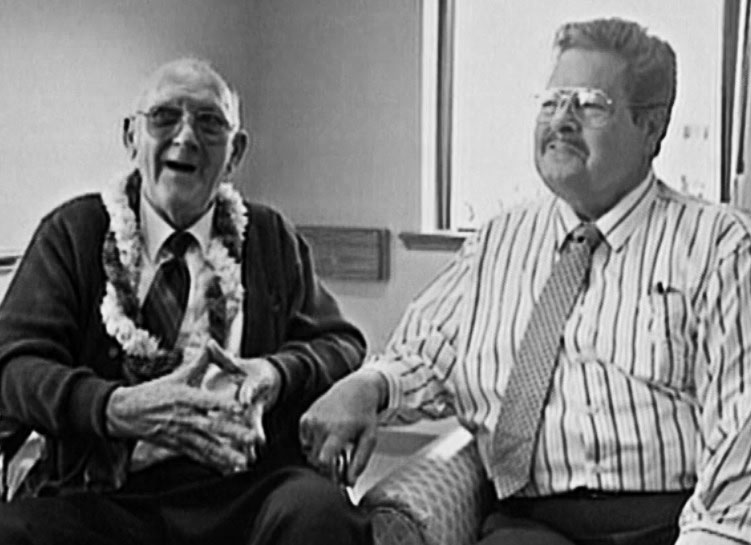

Fritz flew to Frederick in January 1996 and met with Ralph Blank, one of the U.S. soldiers who had been in the Vincken cottage that night so long before. He still had his map and the compass the German corporal had given him.

Blank told Fritz: “Your mother saved my life.” Fritz said the reunion was the high point of his life.

Fritz Vincken later found another of the Americans, but none of the Germans. He died on Dec. 8, 2002, forever grateful that his mother had been given the recognition she so richly deserved.

Fritz Vincken, who was 12 when his mother took in three desperate American soldiers in 1944, and Ralph Blank, one of those soldiers, meet in 1996. [Honolulu Advertiser]

“Now and then, on a clear tropical winter night, I look at the skies for bright Sirius and we always seem to greet each other like old friends. Then, unfailingly, I remember mother and those seven young soldiers, who met as enemies and parted as friends, right in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge.”

Advertisement