Full flying rig of an Allied airman in the Second World War. Forty-five per cent of WW II Allied Bomber Command airmen were killed in action. [iStock; Flight Lieutenant Eric Aldwinckle/CWM/19710261-1217]

Second World War Allied casualty rates in air operations were phenomenally high. Despite their vast accomplishments and invaluable contribution to the war effort, the successes of Bomber Command in particular came at a terrible cost.

According to the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, of every 100 airmen who joined the unit, 45 were killed, six were seriously wounded, eight became prisoners of war and just 41 escaped unscathed (at least physically). Of the [approximately] 120,000 who served, 55,573 were killed, including more than 10,000 Canadians—a fatality rate of 46 per cent. Of those flying at the beginning of the war, only 10 percent survived. Such a loss rate is comparable only to the worst slaughter of the First World War trenches. Only the Nazi U-boat force suffered a higher casualty rate.

With odds like that, it’s no wonder that superstition and ritual was rife among the fliers.

It took various forms, from jinxes to premonitions to amulets or talismans, such as lucky boots, a stuffed toy or a girlfriend’s brooch. Some performed rituals like circling their airplane once before boarding or avoided having a photo taken before a flight. Whatever seemed to work was stuck with, and high-risk sorties usually saw an upsurge in superstitious behaviour.

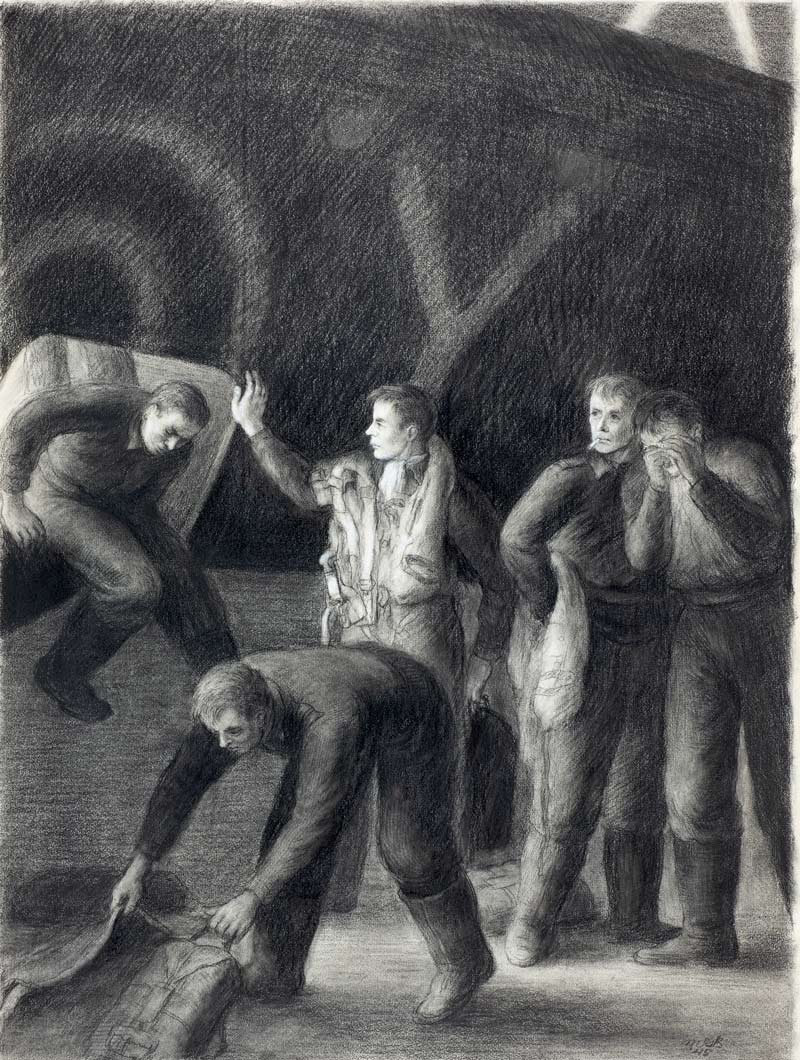

Artist depictions of a chaotic nighttime bombing run over Germany.[Flight Lieutenant Miller Brittain/CWM/19710261-1436]

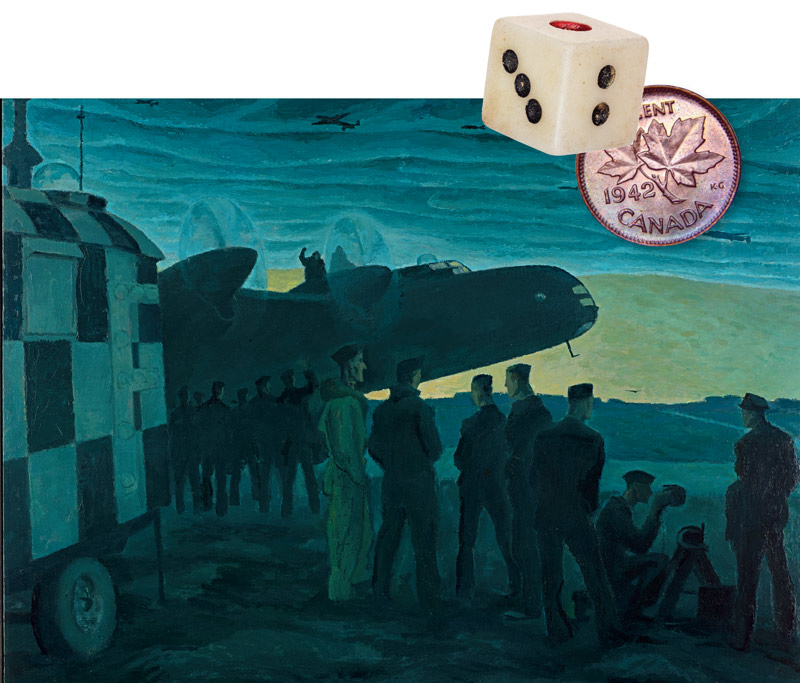

Airmen carried a wide range of lucky charms, from religious medallions and dice and coins to homemade dolls and identification tags. They also often conducted rituals before takeoff, as shown in this painting by Edwin Holgate.[CWM/20130292-008; iStock; coinsandcanada.com]

Common religious objects were understandably popular.

“Around my neck I always wore a medal that a Catholic friend had given me,” recalled Canadian bomber pilot Sydney Percival Smith of the Royal Air Force 115 Squadron, in his 2010 book, Lifting the Silence. The Roman Catholics’ patron saint of travellers was often carried by worshipers and non-Catholics alike.

So were rosary beads, bibles, prayer books and sacred heart medals.

Meanwhile, others carried popular traditional lucky charms, including rabbit’s feet or four-leaf clovers. Items were often perceived as lucky simply because they were carried on flights that happened to come back safely—dice, pennies, silver dollars, scarves, even a champagne cork in one case.

Some fliers thought that more than just an item was necessary for best effect. With or without a talisman, some believed specific actions done in a particular order were necessary to survive a mission or operational tour. For example, Gilbert McElroy, a gunner in the RAF’s 625 Squadron, always planted the palms of both hands firmly on the ground as a signal of his intent to return to terra firma in one piece before climbing aboard his Lancaster and making his way to the rear turret.

Airmen carried a wide range of lucky charms, from religious medallions and dice and coins to homemade dolls and identification tags. They also often conducted rituals before takeoff, as shown in this painting by Edwin Holgate.[Flying Officer Edwin Holgate/CWM/19770692-001]

It was common for RAF aircrews to ritually urinate against an aircraft’s tire before an operational flight—apparently to the point of causing corrosion problems. Before heading out on a long operation, “to pee was vital,” wrote Lancaster pilot Peter Russell of 625, “to do so on the wheel was for luck.”

One Halifax bomber pilot insisted on stroking the ops room cat before a mission to draw good luck from her. “She has become part of his departure routine,” wrote his navigator. Another ritual was witnessed and reported by a Bomber Command station chaplain: the crew arranging themselves equally spaced around their airplane before each mission. Other crews took to circling their bomber once or twice in single file.

Sometimes, the power of a talisman was associated with a specific action. For example, a Typhoon pilot with 609 Squadron named Klaus Adam always turned the signet ring his parents had given him three times before takeoff. He wore it on all operations.

Particular phrases could be important, too. Bert Lester, the mid-upper gunner of an RAF 214 Squadron Stirling bomber, had an especially entertaining ritual as he strapped into his parachute harness. “As he bent and pulled the crotch straps in place,” wrote his Canadian skipper Murray Peden, “he always pulled them too tight and exclaimed in soprano tones: ‘Oooooo, my goodneth;’ then, as he slacked off and clicked the ends home in the quick-release box, he dropped his voice an octave below normal to give a hearty bass, ‘Ah, that’s better.’”

With odds like That, it’s no wonder That superstition and ritual was rife amongst The Fliers.

Airmen carried a wide range of lucky charms, from religious medallions and dice and coins to homemade dolls and identification tags. They also often conducted rituals before takeoff, as shown in this painting by Edwin Holgate.[Norah Wellings/CWM/20130583-002; CWM/20130292-010]

On the other hand, there were things to be avoided so as not to jinx a trip. For instance, volunteering for an operational task in the Fleet Air Arm was thought to be “very unlucky,” indeed “asking for trouble,” wrote Swordfish pilot Charles Lamb in his 1980 memoir, To War in a Stringbag. “If we were told to do something, no matter what, that’s okay; but volunteer—never.”

Captain Denis Boyd, commanding the carrier HMS Illustrious said he could understand that outlook. And within Bomber Command’s 75 Squadron it was even considered a jinx to wish anyone good luck before setting out on a mission.

Some misogyny entered the picture, too. The women with whom fliers came into contact could sometimes find themselves treated as pariahs. For the RAF in the U.K., especially Bomber Command, they were often seen as a problem, since their presence was said to divert men from the all-consuming business of war.

Married life on or near an operational station was considered a distraction, dangerously splitting the loyalties of the husband between his wife and his crew. So, some station commanders banned wives from living in RAF accommodation and tried to dissuade them from moving into nearby villages. Moreover, some married fliers actually thought it bad luck to have their wives live nearby.

Another common sexist jinx: “any innocent member of the WAAF who happened to have two successive boyfriends who failed to return from operations would be labelled a chop girl and shunned,” an observer at RAF station Marham noted of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force.

Aircrews generally considered the number 13 unlucky and those that returned successfully often considered any small detail, even such as the doll of a soldier onboard, a charm. [CWM/20180506-001]

Not surprisingly, numerology played a part in crew superstitions just as it does elsewhere in society. Number 13 was generally considered to be unlucky when used in a call sign, an aircraft serial number or a sortie number. The number 7 was deemed the opposite.

Premonitions of disaster weren’t unusual either. Those crew who experienced them said they involved a sudden and overwhelming sense of imminent catastrophe. They usually came without warning, sometimes while asleep, but often when awake, either to the fliers concerned or to observers.

At times they seemed uncomfortably prescient. In May 1942, Bob Horsley, a wireless air gunner with the RAF 50 Squadron, “had the strongest premonition that we would be shot down.” That night his Manchester bomber was hit with flak so badly over Cologne, Germany, they were forced to bail out.

Some crew members simply became fatalists. After all, fate could appear to be so random: “Some got killed on their first mission while others survived a tour of 35 trips or so and some even completed two tours,” reflected Canadian pilot Donald Smith, who flew Halifax bombers with the Royal Canadian Air Force 425 Squadron in 1944.

“Some never encountered enemy fighters or flak,” Smith continued, “while others encountered them every time they went out. Sometimes one or more crew mates were wounded or killed while the rest of the crew returned [unharmed].”

Regardless of the bewitching beliefs, a variety of behavioural studies have demonstrated clearly that when the future seems particularly uncertain, people are much more inclined to engage in magical thinking and superstitious action as a means of trying to impose some control over a situation.

But it’s seldom logical. There’s little plausible explanation that a pilot survives every mission that starts with him kissing the plane’s propeller because it worked the first time. These rituals became the brain’s justification for survival, even if it had no reasonable impact on the result. However, it could influence self-confidence and therefore performance—so, indeed, potentially impacting success, according to several studies.

“In seeking to make sense of and adapt to the external world, the human brain has evolved in such a way that it constantly seeks to detect patterns in perceived events,” wrote military historian Simon (S.P.) MacKenzie in Flying against Fate: Superstition and Allied aircrews in World War II.

This form of natural learning is generally a good thing, but can on occasion cause problems, because if one event happens after another event, it does not necessarily mean that the first produced the second. Having survived their initial forays into hostile skies, fliers might conclude that what they had done, and the order in which they did it, had led fate to smile on them—and that therefore it was vitally important to not deviate from the established pattern, even in small matters.

“If you’d done it last night and came back and then if you didn’t do it tonight,” as RAF 101 Squadron Lancaster pilot Ken Gray explained in an interview, “my God, you might not come back—so you did all these things.”

He may well be right. Behavioural studies indicate that believing a particular item or action is lucky, actually does—more often than not—translate into better results. And anything that helped bolster the self-control that operational aircrews clearly needed against such overwhelming odds had to have had some charm to it.

These rituals became the brain’s justification for survival, even if that ritual had no reasonable impact on the result.

Aircrews generally considered the number 13 unlucky and those that returned successfully often considered any small detail, even such as the doll of a soldier onboard, a charm. [Flight Lieutenant Miller Brittain/CWM/19710261-1434]

Advertisement