The lush landscape of Medak, a Croatian farming village, is photographed from the rear of an anti-armour platoon house.[Master Corporal Phil Tobicoe/PPCLI Archives/20.39.01]

It was just another company-wide “smoker” at Camp Kananaskis in 1993, but Dangerous Dan was up to his old tricks again.

Acting major of Delta Company, 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI ), Dan Drew was at the base camp party in Sveti Rok, a Croatian village home to a defunct Yugoslav National Army base.

With cases of French wine and gallons of German and Croatian beer available, some Canadian troops saw these get-togethers as more than just a way to relax; it was a classic bacchanal, drunken revelry abounding.

“It was a breeding ground for alcoholism,” said Calgary Highlanders Sergeant Kurtis Sanheim.

Nicknamed “Dangerous” by his fellow soldiers, Drew had some madcap tendencies and access to liquor didn’t make those habits any better. Excessive alcohol consumption was already becoming a problem in 2 PPCLI, but Drew’s company was particularly infamous, boasting some of the battalion’s biggest drinkers.

So, during this smoker, the emotional residue accumulated from witnessing the human atrocities of Yugoslavia’s dissolution in the early 1990s surfaced in Drew as the night slowly expired.

His company had known the monsters of the Croatian Medak area all too well—the civilian cries of ethnic genocide, the corpses burnt beyond recognition, the colonies of maggots that left carcasses wriggling with parasitic life. The company’s role in the United Nations Protection Force was a thankless job that left them bewildered by humanity’s brutality. “We were on the line too long,” 2 PPCLI Sergeant Sjirk Ruurds (Rudy) Bajema said. “We were there for months without a break.”

Operation Medak Pocket, as the UN peacekeeping mission was known, would be the most significant combat Canadian forces had participated in since the Korean War—and yet, 2 PPCLI soldiers, reinforced by militias and other units, had received little to no attention from back home.

So, in that moment, Dangerous Dan decided to be the difference.

In one swift alcohol-drenched gesture, Drew fired his pistol into the night sky, emptying an entire magazine as a salute to his company. There was emotion in his gunfire, a heartfelt apology for the deafening silence of top brass.

And his soldiers didn’t just cheer, they went wild with loyalty for their company.

Unfortunately for Drew, however, the higher-ups didn’t see it that way, and he was demoted to administration company commander. Drew’s punishment, however, later became symbolic of 2 PPCLI’s post-operation experience: one of censorship, chaos and the failure of a system meant to protect soldiers.

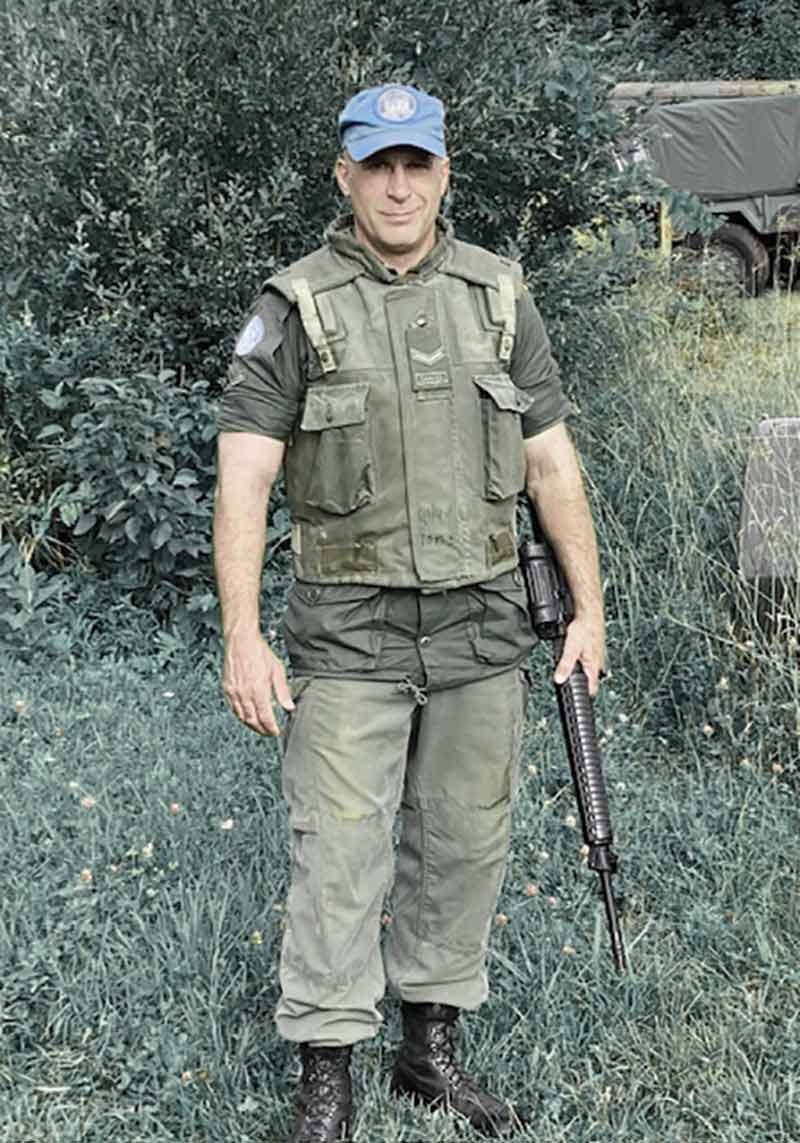

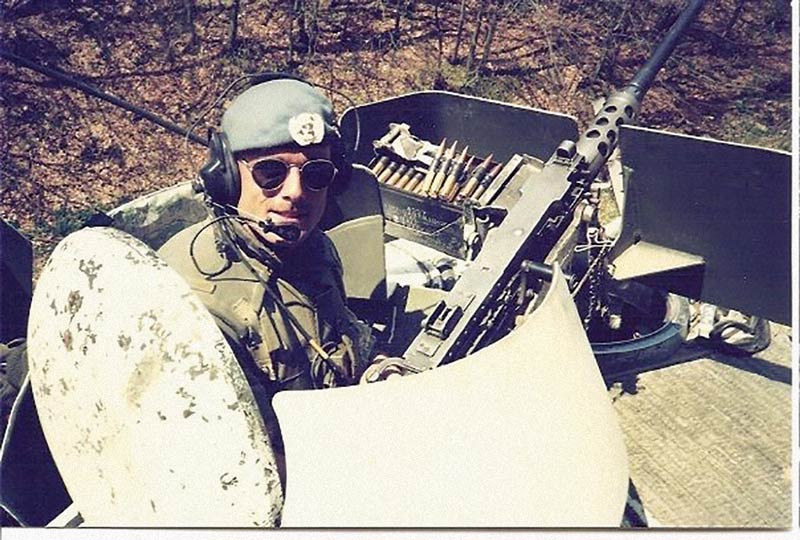

Kurtis Sanheim (blue cap) and team members ready an armoured personnel carrier in Croatia. [Simon Savage]

Drew was one of more than 14,000 Canadians contributing to the UN peacekeeping force in the former Yugoslavia. The security group aimed to ensure stable conditions for peace talks during the breakup of the country’s six republics in 1991. From 1992-1995, Canadians joined personnel from 36 other countries to mediate the messy divorce.

For years, the republics had coexisted peacefully, their similar languages, cultures and customs, along with a centralized communist authority, a binding glue. But the death of Yugoslavian leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980 and the end of the Cold War pushed each republic’s nationalist identity into global politics. The result? A new national order based on blood and religion.

When Serbia, the most powerful of the republics, tried to take the federation’s helm, Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia fought back with their own declarations of independence, manic with nationalist-separatist sentiment. But Croatia and Bosnia were home to numerous ethnic Serbs, many who weren’t comfortable with the new nations they found themselves in. They organized military coalitions against the new governments.

As the paramilitary operations formed, the Yugoslav National Army, propped up by Serbia, fought alongside them to keep Croatia and Bosnia in the Socialist federation. From 1992-1995, the combined forces were amateurish at best and homicidal at worst.

“They would go out and exterminate entire families, shoot them in their homes and outside their homes and line them up,” said Bajema. “I’d seen a bit of it before that. But on that scale, [it] was unprecedented.”

The UN entered the fray in 1992. In Croatia, the peacekeepers mediated a ceasefire between Croatia and its Serbian minority, establishing a buffer zone between the territories held by the two groups. The latter’s Republic of Serbian Krajina included the Medak Pocket, a farming region off the Adriatic coast. The agreement, however, was a far cry from a truce; for the Croats and Serbs, it was a temporary break they needed to increase their readiness for a bloodthirsty enterprise of land grabs, destruction and genocide, or ethnic cleansing.

Called to UN action, Canada readied its own operations, which included the full gamut of wartime weaponry. It was a new look when juxtaposed with the symbolic image of early peacekeepers.

“We were the poster boys for the United Nations,” said veteran Mark E. Meincke, a Canadian Armed Forces’ advocate. “They had a certain baby-hugging image of us that they wanted to maintain. They didn’t want us to be portrayed as the warriors that we were.”

So, in March 1993, 2 PPCLI headed to the region.

Initially, 2 PPCLI were given five months of in-theatre training. During that time, the battalion was a particular standout among the UN forces, particularly after Operation Maslenica in January 1993 when French troops were forced to abandon a UN-protected area against heavy Croat fire.

Witnessing the Canadian military’s skill, the UN force commander, French army General Jean Cot, assigned the Patricias to the theatre’s southern sector, supported by French troops. According to historian Lee Windsor, it was a difficult assignment, not only within the larger mission, but in peacekeeping history.

Indeed, on Sept. 9, the Canadians ended up in the middle of open warfare when 2,500 Croat soldiers invaded the Serbian-held Medak Pocket. For 12 hours, 9 Platoon, ‘C’ Company, felt the hellish rain of artillery and mortar fire, sometimes hitting within 50 metres of its location. Heavy shelling continued in the region for days.

Six days later, on Sept. 15, the Croats agreed to pull back to pre-Sept. 9 lines, thanks to UN mediation and international pressure. But, in working to enforce the new positions, Canadian forces encountered Croat fire, comprised of “small arms, heavy machine gun and in some instances 20 mm cannon fire,” one government report stated. Firefights, up to 90 minutes long sometimes, also occurred during a 15-hour window. At the same time, Serbian forces were sniping at the Croats from behind the peacekeepers.

Still, 2 PPCLI was ordered to establish a crossing line on the main road between the villages of Medak and Gospic and that they could pass it at noon on Sept. 16—until they were delayed by Croat forces.

We used to say that we were treated like used toilet paper, you know, shat on and thrown out.

Sanheim in Croatia in 1993 [Lawrence Hunter]

Something seemed off about the Croatians biding for more time, however. Bombs bursting behind them, the Croats claimed their forces were exploding old mines.

But as the sounds of rifle fire mixed with the rising smoke from the villages beyond the roadblock, the Canadians imagined what this meant: The Croats were killing Serbs in the communities.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant-Colonel Jim Calvin grew restless as the earth shook from explosions, demanding the Croats let the Canadians pass. Ready to play a “lethal game of chicken,” the two sides loaded their weapons and locked onto each other.

However, without any supporting tanks or artillery to stand up against the Croatian 9th Brigade, nor the UN mandate to do so, 2 PPCLI were left to wait, forced to listen to the sounds of death that would later transfix decades-long nightmares for some soldiers.

After an hour waiting, Calvin realized that what he couldn’t breach with muscle, he could push with media. Armed with about two dozen reporters, the standoff was documented by the press, the journalists reporting on how Croatian forces were directly interfering with the UN agreement.

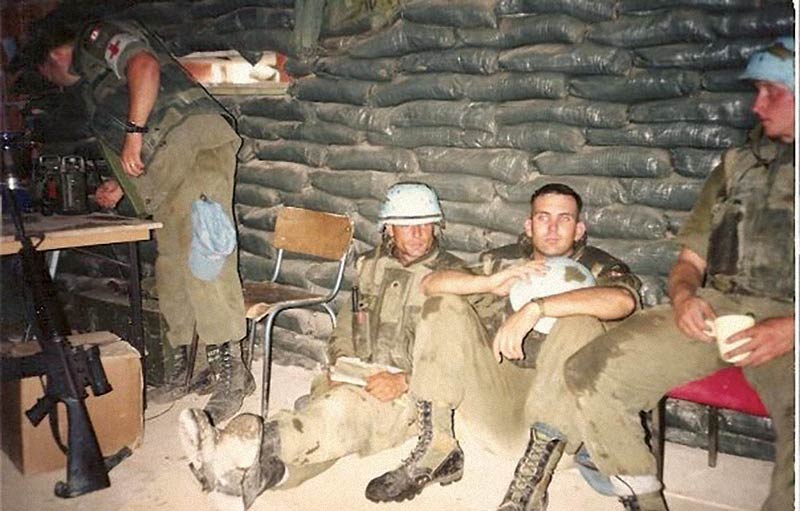

Canadian peacekeepers pause for a photo during their mission.[Courtesy Kurtis Sanheim]

In what would be his “finest moment,” Calvin’s wager paid off, and an hour and a half after they were scheduled to move in, his company cleared the line. Thereafter, 2 PPCLI’s sweep team would initiate their civilian rescue operation.

Remarked Bajema: “I think the leadership [of 2 PPCLI] was pretty bang-on.” Indeed, Calvin received the Meritorious Service Cross for, as his citation noted, carrying “out one of the most successful military operations in support of the humanitarian effort in this theatre.”

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees had indicated that the battalion’s operation could encounter thousands of Serbs in need of rescue from the wartorn region. That part of the mission could have been the most rewarding, a chance to save thousands of lives and prove that the endless mediations and mortar and artillery fire of mid-September weren’t for nothing.

But what 2 PPCLI didn’t know, was that on the other side of the Medak-Gospic crossing line was not a rescue operation, but a murder scene.

“Nobody joins the army for medals,” said Sergeant Sanheim. “You join the army because you want to serve, and you want to do some good, and you want to help protect those that can’t protect themselves.”

Sanheim, now retired, relives his tour as an actor for the 2022 short film Medak.[Courtesy Kurtis Sanheim]

The battalion, however, would end up being required to gather evidence for a potential war-crimes prosecution, a new task the UN force had yet to standardize. This role, coupled with the sweep team’s lack of training in such endeavours and their limited experiences with death, made the smouldering flesh, poisoned wells and slaughtered livestock of Medak a grim reality check for many.

One scene involved two bodies found in a brick chicken coop, bolted shut and still slowly burning. It looked like one person tried to escape, while the other was tied to a chair; both bodies, however, were so horribly charred and maggot-infested that they were beyond identification.

It was only through subtle context clues—long hair, feminine clothing, a purse—that their discoverers theorized that the duo were women. Moving the bodies proved challenging, too, as the limbs fell off when lifted and the heat radiating from the corpses melted the body bags. One warrant officer cooled the bodies by pouring bottled water on them so they could be more easily handled.

“I don’t think [they] ever really got over it,” said Bajema of the soldiers doing such work.

And, so, the sweep team routinely encountered heinous, cold-blooded war crimes. One elderly female victim had been dragged by a rope, had had her left breast slashed, fingers cut from her hand, legs broken and shot in the head four times, while one dead man appearing to be in his 60s had deceptively looked alive because of the sheer number of maggots on his corpse made it seem like his body was shaking.

The sweep team’s leader, Major Craig King, reported to journalist Carol Off for her book, The Ghosts of Medak Pocket: The Story of Canada’s Secret War on how many times the man had been shot: 24 times. “How many bullets in the back and in the head—shot at close range—does it take to kill a sixty-year-old man?” wrote Off.

Out of all these hellish scenes, none had rattled the sweep team as much as that of a blind elderly woman’s “grave.” Lying on top of a rabbit-fur coat, her body was found in a marsh and had been shot at least six times. The soldiers realized that her vulnerability had not been enough to save her—a disturbing truth for many.

The battalion’s hefty to-do list was compounded by a lack of running water nearby. Showers were out of the question, and since the sweep team was equipped only with kitchen gloves and surgical masks while moving bodies, they were often glazed with mud and bodily fluids.

Soon, UN officers and volunteers alike began finding more and more excuses to avoid going out with the sweep team and instead exercised their right to leave the corpse-hunting business behind. Out of the thousands of potential Serbian lives that could have been saved, according to the UN, 2 PPCLI only found 16 bodies and no survivors.

The genocide had pulverized the sweep team’s morale, leaving it surrounded by weapons, war and the overwhelming question of “what if?”

The sense of failure from not finding any survivors, mixed with the guilt from not crossing the Medak-Gospic line sooner, had left a mental scar on the young soldiers, and it was starting to show.

“We felt we could have done more,” confessed Bajema.

Sergeant Sjirk Ruurds (Rudy) Bajema on patrol in Croatia[Courtesy Rudy Bajema]

While alcohol abuse became an increasing issue in the battalion, spurring such incidents as Dangerous Dan’s pistol salute, other significant signs of combat stress began to surface, too.

One soldier, for instance, was found threatening a fellow officer with a bayonet and rifle during guard duty, while a Delta Company cook had cut his wrists and grilled his hands to escape the devastation.

Other soldiers, however, went from miserable to mutinous. One private pounded a master corporal’s head against a concrete floor during a late-night smoker, while other soldiers exuded a “cowboy mentality,” digging graves for senior personnel and carrying extra rounds in case they might need them.

Later, it was discovered that as many as 12 soldiers had plotted to kill Delta Company members.

These instances weren’t a result of moral delinquency. The actions of 2 PPCLI members in battle and beyond had proven that a finer lot of peacekeepers couldn’t have existed. Instead, it was from the sheer helplessness and hopelessness of their situation—just as invalidated from the zero-survivor count as they were from Ottawa’s complete lack of contact with 2 PPCLI during the posting.

“[But] when they got home,” said Bajema, “they had to fight another battle.”

When some 2 PPCLI members arrived back in Canada in October 1993, their “hero’s welcome” consisted of a box of doughnuts, a coffee urn, and…silence.

“We used to say that we were treated like used toilet paper,” said Meincke, “you know, shat on and thrown out.”

Soldiers soon realized that most Canadians had no idea that the CAF was even in Croatia. And when soldiers tried to tell civilians about what had happened, people would flat-out deny the troops’ experiences.

“[They would say,] ‘well, if that was true, I would have heard about it on the news.’ Okay, narcissist,” Meincke quipped. “If you didn’t hear about it, it didn’t happen. Okay, centre-of-the-universe.”

Some believe that such a hushed homecoming was all strategy, however, aiming to quell military coverage in the wake of the Somalia affair. Earlier that year, media organizations had published graphic details of a Somali teen tortured and killed by Canadian paratroopers on a peacekeeping mission. The utter brutality of the teen’s treatment unravelled the CAF’s reputation for military competence and professionalism. According to historian Windsor, this fuelled a public perception that Canadian soldiers were “poorly trained, incompetently led, badly equipped and quite often racist.”

While the UN declared 2 PPCLI’s work in the former Yugoslavia an exemplary display of modern peacekeeping, the unit still felt tarnished by the Somalia affair. 2 PPCLI was silenced and some members felt shamed.

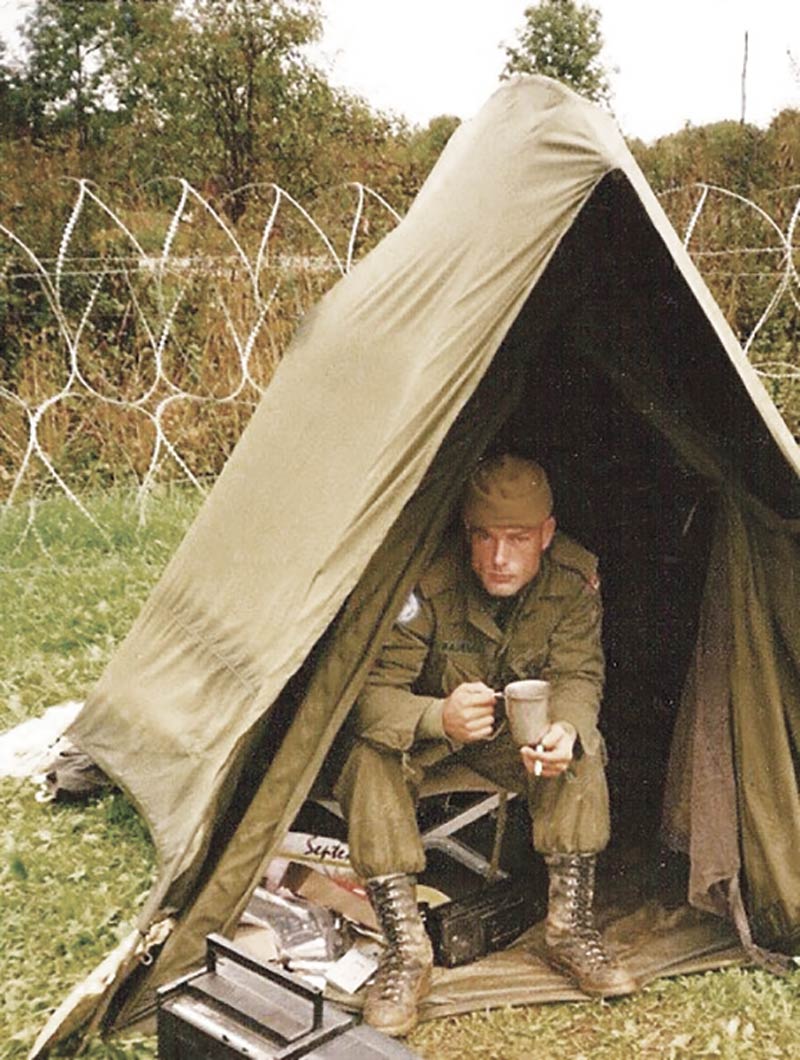

Sergeant Sjirk Ruurds (Rudy) Bajema sitting in his tent outside company headquarters[Courtesy Rudy Bajema]

Helmeted in HQ with fellow peacekeepers during an artillery shelling.[Courtesy Rudy Bajema]

Operation Medak Pocket would be the most significant combat Canadian forces had participated in since the Korean War.

“It was a crappy time to be in the army,” noted Bajema.

This blow was compounded by the absence of post-deployment decompression programs for many reservists who had served with the Patricias in the Balkans and needed to move from station to station quickly.

“They kind of went like ghosts into the winds,” said Bajema.

So, unlike the First and Second world wars or even the Korean War, many 2PCCLI members had relatively very little time to transition back into civilian life, leaving them physically in Canada, but mentally still in Medak.

“[None of the soldiers] actually came home,” noted Meincke. “[A] hollowed out version of them came home.”

Without the validation combat soldiers often need to give moral legitimacy to their actions, many experienced broken marriages, homelessness and mental/physical illnesses. One of the most common health issues 2 PPCLI members dealt with was post-traumatic stress disorder, an illness that had, up until that point, largely been defined as such only in clinical circles.

And while veterans tried to bring this to the government’s attention, particularly in a 1998 letter written by Calvin to the head of the army, Parliament was silent on the matter. It was only when one veteran started talking to the media—a bold act given the military’s historically tight-lipped nature—that the government considered the matter. But not in the way veterans had hoped for.

Rather than receiving the long-awaited thank-you they expected, 2 PPCLI members faced a vicious series of criminal investigations into leadership oversights and company discipline. Most soldiers deemed the inquiries “witch hunts” and suspected they were another political strategy to deny accountability.

“I felt like the government was abandoning us,” said Bajema.

While 2 PPCLI had received the UN Force Commander’s Commendation in 1993, one of only three such awards ever given to United Nations peacekeeping forces, it wasn’t until 2002—nine years later—that Governor General Adrienne Clarkson awarded the battalion the Commander-in-Chief Unit Commendation in recognition of its “courageous and professional execution of duty during the Medak Pocket Operation.” Some members also finally received the pensions and health care services they needed, too.

“It [was] bittersweet,” said Bajema.

Additionally, 2 PPCLI’s thorough documentation of genocide, or ethnic cleansing, in the Medak Pocket set an international standard for UN peacekeepers, leaving its mark on how evidence for war crimes trials is recorded and documented.

Most importantly, though, the operation brought the concept of post-traumatic stress disorder and veteran mental health in Canada from fringe medical jargon to mainstream conversation, spurring a mental health awareness campaign that continues to grow.

And while there is still much work to be done on that front, Medak veterans such as Bajema, Meincke and Sanheim are still trying to make a difference. Meincke runs a nationally acclaimed podcast, “Operation Tango Romeo,” on veteran trauma recovery, while Bajema and Sanheim both spread awareness through talks on PTSD and participation in veteran peer support programs.

Said Bajema: “I couldn’t be prouder of all the guys who went through all that.”

Advertisement