An early 19th-century portrait of the legendary leader Tecumseh by an unknown artist.[Baldwin Collection of Canadiana/Toronto Public Library]

He was a visionary and a pragmatist, a warrior and a diplomat, an enemy and a hero whose legend and likeness penetrated deep and long into the very culture he fought.

“The red men have borne many and great injuries; they ought to suffer them no longer,” declared the Shawnee chief Tecumseh in 1810. “My people will not; they are determined on vengeance; they have taken up the tomahawk; they will make it fat with blood; they will drink the blood of the white people.”

A powerful orator, his speech to the Osage Nation came as he sought to rally fewer than 100,000 Indigenous Peoples in the cause of halting an expanding population of nearly seven million Americans, some 400,000 of whom were now living in traditional Indigenous territories west of the Appalachian Mountains.

His recruitment campaign took him far from his frontier base on the Tippecanoe River in northern Indiana north into Canada and south to the Gulf of Mexico.

“Brothers, if you do not unite with us, they will first destroy us, and then you will fall an easy prey to them,” he warned the Osage three-quarters of a century before the last of the Plains Indians were forced onto reservations and into residential schools—and a way of life disappeared forever. It is now considered one of history’s great genocides.

“They have destroyed many nations of red men because they were not united,” said Tecumseh. “They wish to make us enemies, that they may sweep over and desolate our hunting grounds, like devastating winds or rushing waters.”

Word of the Shawnee’s ambitions spread rapidly, leading William Henry Harrison, the governor of the Indiana Territory, to twice negotiate with the dynamic leader face-to-face.

Harrison characterized his adversary as “one of those uncommon geniuses who spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things.”

Tecumseh was, as writer Deborah Hufford put it, “one of the greatest Native American chiefs…a man of nearly clairvoyant vision who launched a massive campaign against whites marching west, the first—and last—best hope for Native Americans to save their ancestral lands.”

He would take his confederacy and ally with the British and Canadians in the War of 1812, only to die in battle a year later, his cause destined to be lost but, far short of his aims, his legacy as one of America’s most celebrated military foes and cultural heroes secure.

Tecumseh is believed to have been born in March 1768, possibly during a meteor shower, in a sprawling settlement of wigwams and bark cabins on the bluffs above present-day Ohio’s Mad River, northeast of Dayton. He was given the prescient Shawnee name meaning “shooting star” or “panther crouching for his prey.”

The Shawnee were fierce warriors and conflict imposed itself on his life from the beginning. His father, the war chief Pukeshinwau, would die in battle during Lord Dunmore’s War, a 1774 conflict pitting Shawnee and Mingo warriors against white settlers of the Virginia colony.

While dealing with his father’s death at the hands of the British was difficult for young Tecumseh, he had already come to learn the lesson that life is nuanced in greys, not delineated in black and white. He had learned it from his father himself. He would come to envision a gentler society for his people and grew up with a strong sense of justice for all, including his enemies.

“A brilliant orator and warrior and a brave and distinguished patriot of his people, he was intelligent, learned, and wise, and was noted, even among his white enemies, for his integrity and humanity,” Alvin M. Josephy Jr. wrote in American Heritage

magazine in 1961.

Tecumseh may have witnessed his first combat at the Battle of Piqua in 1780 near his home on the Mad River. He was 12 years old. At 18, he became a full-fledged warrior. The young man grew to nearly six feet tall, a handsome, imposing and muscular warrior-poet with an arresting presence.

In 1790, when Tecumseh was 22, he fought alongside Chief Little Turtle against General Josiah Harmar in western Ohio. Fighting under order from then-president Washington, Harmar’s army lost. Nearly two hundred of his troops were killed or wounded in one of the U.S. military’s greatest defeats to an Indigenous force.

For more than a century, colonists had been pushing the Indigenous Peoples of eastern and southern North America west from their ancestral homelands in the regions of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi.

As a result, Tecumseh began building a vast, multi-tribal confederacy ranging from present-day Michigan to Georgia to fight colonial expansion. The whites brought more than guns and plows to the frontier territories. Smallpox and other diseases for which the Indigenous populace had no defence wiped out entire populations.

In the Great Lakes and middle Mississippi River regions, Tecumseh’s Shawnee were joined by Potawatomi, Winnebago, Kickapoo, Menominee, Odawa and Wyandot. Initially, he was met with strong resistance from chiefs who had already signed treaties.

In 1809, Harrison had negotiated the Treaty of Fort Wayne, which ceded more than 12 million hectares of land to the government. Tecumseh, who lived north of the area, maintained the deal was illegal. He met with Harrison in 1810 and 1811 and refused to recognize the treaty.

“The only way to stop this evil [loss of land] is for the red man to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land, as it was first, and should be now, for it was never divided,” he told Harrison.

Harrison insisted the agreement was binding. Replied Tecumseh: “Sell a country?!? Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children? How can we have confidence in the white people?”

Known to the white pioneers as the “yaller devil,” Tecumseh, TOO, was said to have prophetic powers.

It’s believed he also reached out to South Appalachian Mississippian tribes, including the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole.

“Where today are the Pequot?” he asked them. “Where are the Narragansett, the Mohican, the Pocanet and other powerful tribes of our people?

“They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man…Sleep not longer, O Choctaws and Chickasaws…Will not the bones of our dead be plowed up, and their graves turned into plowed fields?”

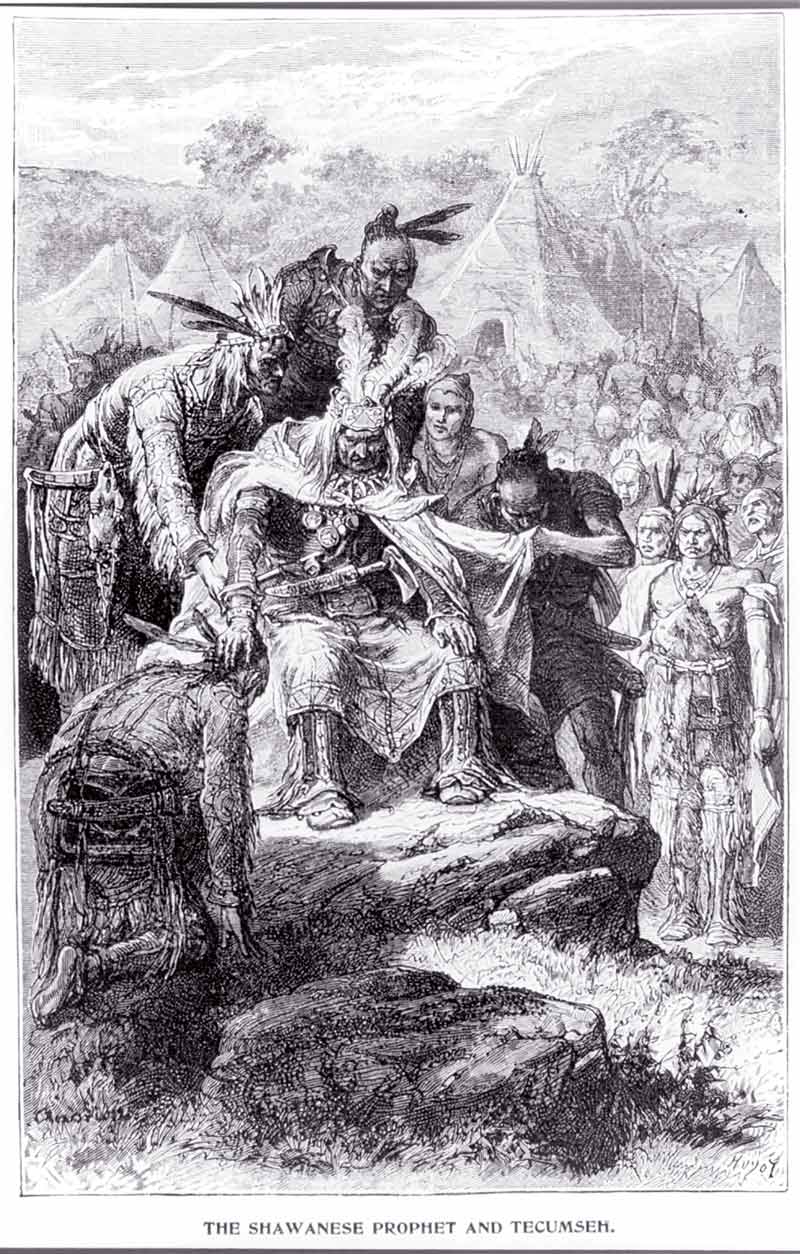

A wood engraving from the mid-19th-century depicts Tecumseh’s brother Tenskwatawa, known as The Prophet, meeting with other First Nations.[Library of Congress/2012645311]

Tecumseh’s cause was aided by his younger brother, Tenskwatawa, a religious visionary known as The Prophet who claimed to have powerful visions decreeing that tribes must unite to fight the evil spirits taking their lands.

Trying to discredit Tenskwatawa, Harrison issued a challenge, reported by a newspaper of the day: “If he is really a prophet, ask him to cause the Sun to stand still or the Moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow or the dead to rise from their graves.”

Tenskwatawa then summoned a sunless sky, which was in effect realized in the form of a solar eclipse.

In 1808, the brothers established Prophetstown, where the confederacy would form its base at the confluence of the Wabash and Tippecanoe rivers.

Known to the white pioneers as the “yaller devil,” Tecumseh, too, was said to have prophetic powers. Legend has it that when the Muscogee refused to join his alliance, he issued a threat: if they did not join him before he reached Detroit, he would simply stomp his feet and the earth would shake down the great Mississippi and their villages would be destroyed.

Within days, on Dec. 16, 1811, the region was jolted by a massive earthquake—caused, says today’s U.S. Geological Survey, by the New Madrid fault system that spans five Midwestern states. The shaker was estimated to have been stronger than the one that destroyed San Francisco and killed more than 3,000 people in 1906.

Tecumseh’s confederation fought U.S. forces from August 1810 to October 1813.

Tecumseh readily joined the British in the War of 1812 after U.S. forces had razed his village in the November 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe. [Library of Congress/Wikimedia]

In November 1811, while the chief was away building his coalition among southern tribes, Harrison assembled some 1,000 troops and attacked Prophetstown, dealing the coalition a devastating defeat at the Battle of Tippecanoe.

In what some consider the first engagement of the War of 1812, the American troops burned the encampment to the ground after Tenskwatawa and its residents abandoned it.

The pragmatist in Tecumseh subsequently brought him into an alliance with the British who were likewise at odds with the Americans at the time.

A month after U.S. troops invaded Upper Canada in July 1812, Major-General Isaac Brock travelled to Amherstburg to organize the British response, an attack on Fort Detroit. He met with Indigenous warriors to negotiate an alliance to fight the Americans. Tecumseh stood out among the assembled chiefs.

“I have heard much of your fame, and am happy again to shake by the hand a brave brother warrior,” the Shawnee leader told him. Brock gave him his sash.

The British general was progressive for his time, saying of his Indigenous brethren in a July 22, 1812, speech: “But they are men, and have equal rights with all other men to defend themselves and their property when invaded.”

Brigadier-General William Hull had just led his forces into Canada. Haunted by Indigenous atrocities, he then withdrew back across the border to Detroit.

On Aug. 16, Tecumseh led a multi-tribal group of warriors and, with a combined force of Canadian militia and British regulars, surrounded the city’s fort. Brock could smell Hull’s fear and so, no doubt, could Tecumseh. The Indigenous warriors paraded past the fort for psychological effect.

Brock sent his adversary a surrender demand.

“The force at my disposal authorizes me to require of you the immediate surrender of Fort Detroit,” he wrote. “It is far from my intention to join in a war of extermination, but you must be aware, that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond control the moment the contest commences.”

With the prospect of imminent massacre by “hordes of howling savages” hanging over his head, the aging and ailing Hull surrendered the garrison and his 2,500-man army having barely fired a shot. He was rumoured to have been drinking heavily before the capitulation and is reported to have said that the Indigenous warriors were “numerous beyond example” and “more greedy of violence…than the Vikings or Huns.”

The attackers captured 33 cannons, 300 rifles, 2,500 muskets and the brig Adams, the only armed American vessel on the Great Lakes at the time. The British navy put it into service.

Brock sent the 1,600 captured Ohio militiamen south, providing them with an escort until they were out of danger. Most of the Michigan militia had already deserted. The 582 American regulars taken prisoner were sent to Quebec City.

Hull was court-martialled in 1814 and convicted of cowardice and neglect of duty. He was to be shot but, in deference to his service in the Revolutionary War, President James Madison commuted the sentence and dismissed him from the army instead.

The British victory reinvigorated the beleaguered militia and civil authorities of Upper Canada, boosting their prospects and morale, and it inspired tribes in Tecumseh’s confederacy to take up arms against U.S. outposts and settlers.

His warriors would go on to strike deep into the United States, attacking forts and sending terrified settlers fleeing back toward the Ohio River. It wouldn’t be until after Tecumseh’s death that they would at last begin to “realize that a native of soaring greatness had been in their midst,” Josephy wrote.

Harrison, recalled to command U.S. forces in the west, spent nearly a year converting militiamen into some semblance of professional soldiers. In the fall of 1813, he invaded Upper Canada. The British commander, Henry Procter, panicked.

Fighting non-stop for days, Tecumseh and some 500 warriors screened the British retreat, but on Oct. 5, Harrison caught up with Procter at the Thames River near Moraviantown. The British general ignominiously fled and his regular troops surrendered.

The Shawnee chief is said to have had a vision foretelling his own fate. He removed the British general’s red uniform he usually wore in battle and donned his Shawnee leggings and deerskin tunic for the last time. He handed his blade to one of his chiefs, saying: “Give this to my son when he becomes a warrior and able to wield a sword.”

The pair had exchanged sashes in mutual respect after first meeting earlier that year. [LAC/2835873]

“If it were not for the vicinity of the United States,” Tecumseh “would perhaps be the founder of an empire.”

Tecumseh and his exhausted ranks took up positions in a patch of swampy woodland. The chief said he would retreat no farther. Having dispatched with the British, Harrison sent dragoons and infantry into the thickets.

After an hour of fierce fighting, Tecumseh was killed, or so it is believed. He was never seen alive again—his ultimate fate dependent on which side was telling the story. For all practical purposes, however, his Indigenous resistance died with him.

Hungry for an American victory after a humiliating year of losses, the first reports from the Battle of the Thames claimed Harrison’s brave boys had overcome 3,000 superb warriors led by the great Tecumseh.

Tecumseh and Major-General Isaac Brock oversee the American surrender of Detroit in August 1812. [Alfred Morton Wickson/Wikimedia ]

The man who apparently had the most credible claim to killing him, a Kentucky cavalry commander named Richard Johnson, eventually won a Senate seat, then the vice-presidency in 1836, with his supporters chanting “Rumpsey Dumpsey, Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh.”

Buoyed by the jingle “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” Harrison became president four years later. “If it were not for the vicinity of the United States,” Harrison once said, Tecumseh “would perhaps be the founder of an empire that would rival in glory that of Mexico or Peru.”

Instead, an October 2021 paper published in the scientific journal Science, concluded that the Indigenous Peoples of the United States have lost nearly 99 per cent of the land they historically occupied.

In an unprecedented study spanning 300 years and including nearly 400 tribes, researchers found that 42 per cent of those represented in historical records have no recognized land today. The average size of Indigenous tribal lands in America today is a mere 2.6 per cent of their historical territories and most are far from their original sites: on average, tribes were forced to move 241 kilometres, most often to areas settlers considered less desirable and, as it turns out, with fewer natural resources, too.

In addition, the data shows that present-day tribal lands are more at risk from climate change than their historical areas and are more susceptible to extreme heat and drought.

Chief Oshawana served as his lead warrior.

On Dec. 2, 1820, the Indiana Centinel of Vincennes published a letter singing the praises of the great chief, and hearkening back to Harrison’s speculations on what might have been.

“Every schoolboy in the Union now knows that Tecumseh was a great man,” it said. “His greatness was his own, unassisted by science or education. As a statesman, warrior and patriot, we shall not look on his like again.”

An unfortunate namesake

Union General William Tecumseh Sherman was key to defeating the Confederacy in the 1861-1865 U.S. Civil War, then led the American army against Indigenous nations in the continuing wars once fought by the Shawnee chief for whom he was named.

Sherman, like Tecumseh himself, was born in Ohio. According to the general’s memoirs, his father Charles, justice of the state’s supreme court, “caught a fancy for the great chief of the Shawnees, ‘Tecumseh.’”

Recognizable by his haggard, battle-worn look in period photographs, Sherman was a master tactician who developed a reputation for ruthlessness due to his scorched earth policy against the Confederate states during the Civil War.

Kentucky cavalry commander Richard Johnson kills Tecumseh during the October 1813 Battle of the Thames (below), where Chief Oshawana (top) served as his lead warrior.[Indiana University/Wikimedia]

Sherman succeeded General Ulysses S. Grant as commander of the western theatre of operations a year before the war ended, won at Vicksburg and Atlanta, and led the subsequent March to the Sea, which sounded the death knell to the Confederacy’s bid for independence—and slavery.

Along the way, his armies laid waste not only to military stockpiles, bridges and railroads, but to homes, farms and livestock in a calculated campaign to break Southerners’ will to fight. Such tactics would come to be known as “total war.”

Yet, after accepting the surrender of the Confederate armies in the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida in April 1865, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton deemed the terms Sherman negotiated too generous and ordered Grant to modify them.

With the war’s end, American eyes turned westward. “We are not going to let thieving, ragged Indians check and stop the [railroads’] progress,” Sherman wrote Grant in 1867.

Grant was propelled to the presidency in 1869 after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and appointed Sherman his successor as commanding general of the army. Sherman served until November 1883.

He directed the U.S. Army as it crossed the Great Plains and employed the same destructive tactics in exterminating and relocating the last Indigenous nations. The Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche and Apache all suffered significantly during Sherman’s 19th century Indian Wars.

Kentucky cavalry commander Richard Johnson kills Tecumseh during the October 1813 Battle of the Thames, where Chief Oshawana served as his lead warrior. [Wikimedia]

“We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children,” Sherman once said. A year later, he issued an order permitting the Sioux’s “utter annihilation.”

“The more [Indians] we can kill,” said Sherman, “the less will have to be killed in the next war, for the more I see of these Indians, the more convinced I am that they all have to be killed or to be maintained as a species of paupers.”

In his 1878 annual report to Sherman, General Philip Sheridan, who led American forces in battle against Indigenous warriors, acknowledged the plight of Native Americans starving on reservations, where they lived on broken promises.

“We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay among them, and it was for this and against this they made war,” wrote Sheridan, also a Civil War veteran.

“Could anyone expect less? Then, why wonder at Indian difficulties?”

Advertisement