As Canadian commanders planned to assault Mont Sorrel, Germany attacked.

Two weeks and almost 9,000 casualties later, Canada recovered the lost ground

On May 25, 1915, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division officially became part of the British Expeditionary Force with headquarters at Shorncliffe Army Camp in Sussex, England. The men had been recruited during the fall of 1914, but as there were no winter quarters available for an 18,000-man division, battalions remained scattered across the country attempting to train, without proper equipment, in the snows of a Canadian winter.

The division’s three infantry brigades were regionally based, the 4th from central Ontario, the 5th from Quebec and the Maritimes and the 6th from the West. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were represented in locally recruited battalions, the 25th and 26th. French-speaking Canadians had been marginalized in the formation of 1st Division, but after a delegation of prominent leaders, including Sir Wilfrid Laurier, petitioned Ottawa and promised $50,000 for initial expenses, the government agreed to mobilize the 22nd Battalion as a French-language unit within 2nd Division. Two other Quebec battalions, the 24th (Victoria Rifles) and the 23rd (which became a reserve battalion), were also recruited.

The new division was commanded first by Major-General Sam Steele, a 66-year-old authentic Canadian hero who fought in the North West Rebellion and led Lord Strathcona’s Horse in the Boer War. Steele was selected by Minister of Militia and Defence Sam Hughes, who wanted a Canadian in command. Field Marshal Lord Kitchener was equally determined to appoint an experienced officer “to do justice to the troops.”

Kitchener’s offer to allow Canada to choose any British general on the “unemployed active list” enraged Hughes. He believed that British commanders at Ypres had sacrificed Canadian lives and he was in no mood to accept claims of British superiority. An agreement to appoint Brigadier Richard Turner to command 2nd Division while Arthur Currie took over 1st Division satisfied Hughes, but he had to accept the promotion of Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson to command the Canadian Corps.

While in England, 2nd Division was able to draw on officers and NCOs with experience on the Western Front for both leadership and training. Lieutenant-Colonel H.D. de Prée, a veteran British officer, returned from France to become senior staff officer, and other staff college graduates provided the administrative skills required to integrate the Canadians into the British way of war. There were also opportunities for junior officers to attend battle schools and take part in battalion, brigade and even divisional level exercises. When it crossed to France, the 2nd Division was, by 1915 standards, well prepared for trench warfare on the Western Front.

After a series of costly and frustrating battles in the first half of 1915, British High Command hoped to avoid participation in a major offensive until more high-explosive shells were available. German success on the Eastern Front and French demands for British assistance in yet another attempt to capture Vimy Ridge forced Kitchener to agree to a battle immediately north of Vimy in flat terrain punctuated by slag heaps.

The Battle of Loos may have had to be fought to support the French but it was General Sir Douglas Haig who decided it was to be a breakthrough battle aimed at Douai, Valenciennes and beyond. The first use of chlorine gas by the British armies would, he argued, facilitate the break-in battle, and by using the “utmost energy,” the troops were to press on through the German positions. Infantry and cavalry reserves were available for exploitation. Haig converted an action intended to contain German reserves into one of the great disasters of the war. Some 50,000 British soldiers were lost at Loos, almost half killed or missing.

To assist the British advance, a Canadian diversion with artillery fire and a simulated gas attack, carried out by 2nd Division, occupied the Germans opposite at a cost of 100 Canadian casualties. The men of the 2nd Division had at least witnessed the reality of combat on the Western Front.

The Canadians spent the summer and fall of 1915 holding the line in the Ypres Salient. It was a miserable period of trench warfare punctuated with raids and small company-level attacks, but no major actions. The Canadians were out of the line in December when the Germans conducted an experiment with a new gas. The attack at Messines began with the release of chlorine and an intense shrapnel bombardment. The enemy then fired artillery shells containing colourless phosgene, hoping to create panic among the defenders, whose gas masks could not cope with high concentrations of the new gas. Despite heavy casualties, including 120 who died from inhaling phosgene, the British troops held.

During the last weeks of 1915, both adversaries developed plans for operations in 1916. At the Chantilly Conference on Dec. 6, 1915, an agreement to launch co-ordinated offensives on the Russian, Italian and Western fronts was reached, with spring 1916 as the preferred date. The German commander General Erich von Falkenhayn pre-empted these plans with his decision to “bleed the French Army white” in Verdun.

Von Falkenhayn also ordered a series of small-scale diversionary attacks and on Feb. 14, the German forces in the Ypres sector captured a key position known as the “Bluff.” General Herbet Plumer, commanding the Second British Army, decided to commit substantial forces to recover the Bluff and he decided to hit back at the enemy by capturing the feature known as the “Mound,” an artificial earth pile at St. Eloi that overlooked the British positions.

The St. Eloi sector had been the scene of numerous mine explosions and a British tunnelling company had just completed work on six shafts that reached under the German trenches. As the mines under the enemy were exploded, the Third British Division seized the position. The Mound was practically destroyed and the new craters added to the complexity of the ground. Then the rains began.

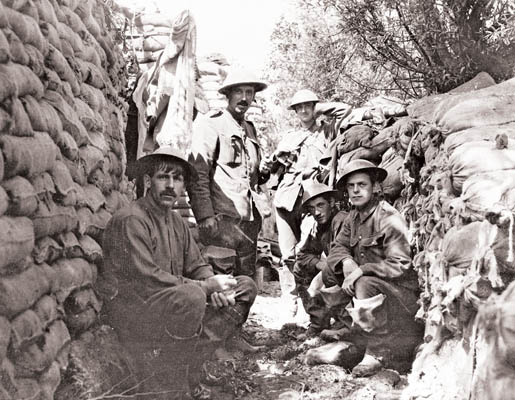

The Canadian Corps was scheduled to relieve the British after the battle but despite protests from Major-General Turner, who crawled through mud to survey the situation, Alderson accepted Plumer’s order to carry out a relief in the midst of a chaotic battle. The British official history notes that the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade, “wearing steel helmets for the first time—fifty per company,” took over a “barely distinguishable line” among four large craters. The trenches, a series of waist-deep and watery mud holes could not be drained and the enemy bombardments demolished the newly strung barbed wire. After three weeks of futile combat, the battle for St. Eloi ended. In the words of the British Official History, “Fighting over a morass of mud and in bad weather had imposed unheard of misery on the troops and both sides were glad to bring it to a close.”

The battle of St. Eloi led to another crisis in command relationships when Alderson, the Corps commander, sought to dismiss Turner and one of his brigadiers for alleged incompetence. The new British Commander-in-Chief, General Haig, refused to confirm the decision because of “the danger of a serious feud between Canadians and the British…and because in the circumstances of the battle for the craters mistakes are to be expected.” Canadian historians tended to side with Alderson and condemn Turner, noting that political interference from Hughes and his representative Sir Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) saved Turner and cost Alderson his job as Corps commander. But the case against Turner is made on Clausewitzian grounds, suggesting that a competent commander is by definition one who reacts properly and masters the situation. If this standard is applied uniformly, few generals on either side make the grade, and we are left with fallible, stubborn, imperfect humans, unable to foresee the future and almost always overwhelmed by the chaos of battle.

The enemy fired shells containing

colourless phosgene, hoping to create

panic among the defenders.

The new Canadian Corps commander was Sir Julian Byng, a veteran of the South African war who had commanded the Cavalry Corps in France before earning good reports for his leadership in supervising the withdrawal of colonial forces, including the Newfoundland Regiment, from Helles and Suvla Bay in Gallipoli.

Byng was the grandson of a field marshal and a prominent member of the English aristocracy. Like many other British officers, he retained his schoolboy nickname, “Bungo.” His self-confidence and easy manner won him friends throughout the army and especially within the Canadian Corps. Historians have repeatedly lavished praise on Byng. “He was the single most important figure in transforming the Canadian Corps into a battle-hardened formation,” writes Tim Cook. Perhaps so, but in early June 1916, the problems confronting Canadian and British troops in the Ypres Salient could not be fixed by a Corps commander, however charismatic.

When Byng took over, the Canadians were responsible for the sector of the Ypres Salient from the Menin Road to south of St. Eloi. The recently formed Third Division commanded by Major-General Malcolm Mercer held the left of the line, clinging to the only part of the Ypres ridge still in Allied hands, an area the official Canadian historian, G.W.L. Nicholson, described as “a flat knoll called Mount Sorrel and two slightly higher twin eminences, ‘Hill 61’ and ‘Hill 62,’ the latter known as Tor Top.” From Tor Top, a “broad span of largely farm land, aptly named Observatory Ridge, thrusts nearly a thousand yards due west between Armagh Wood and Sanctuary Wood.”

Despite the tactical importance of the ridge-top positions, Second Army failed to respond to growing signs that a German attack was imminent. The Canadians who took over the sector were just beginning to make changes when the attack struck. On June 2, German divisions of the XIII (Royal Württemberg) Army Corps, employing the heaviest bombardment yet used in the area, overwhelmed the Canadian positions. General Mercer was killed and Brigadier A.S. Williams taken prisoner, adding to the chaos. The Germans quickly dug in overlooking Ypres.

Byng, who had been with the Corps less than a week, ordered an immediate counterattack that proved to be a costly failure. He then stepped back and organized an intensive artillery-based attack employing two composite brigades of Arthur Currie’s 1st Division veterans. The original line was restored following an equally heavy Canadian bombardment and quick advance on June 13. The two weeks of close combat, including the loss of Hooge, a village on the Menin Road, cost the Corps close to 9,000 casualties, including hundreds of shell-shock cases. But the Battle of Mont Sorrel was quickly forgotten because, on July 1, 1916, the Battle of the Somme began.

Advertisement