![CoppLead Canadian soldiers advance during Operation Spring, July 25, 1944. [PHOTO: KEN BELL, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA131378]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/CoppLead1.jpg)

General Bernard Montgomery’s “armoured blitzkrieg,” Operation Goodwood, and its Canadian component, Operation Atlantic, ended in rain and confusion on July 20, 1944. The next day, Montgomery and his army commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Dempsey, met to consider their options. News of the failed assassination attempt against Hitler was discussed as was the postponement of Operation Cobra, the major American offensive originally scheduled for July 20. The two British generals agreed they could not wait for the Americans; they would launch their attack south of Caen as soon as possible.

Montgomery explained his plans in a letter to the Supreme Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. His aim was to “try and bring about a major enemy withdrawal from in front of Brad (United States Army General Omar Bradley) by a series of left-right blows east and west of the Orne (River), to keep the enemy guessing, followed by a heavy blow towards Falaise.” The first blow was code-named Operation Spring and was assigned to Lt.-Gen. Guy Simonds and 2nd Canadian Corps which, in July, was operating under Second British Army.

Simonds discussed the details of the operation “fully” with Dempsey and obtained his approval, but Operation Spring was Simonds’ plan. He designed it as a three-phase battle involving the two Canadian infantry divisions and 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, plus the 7th and Guards Armoured divisions.

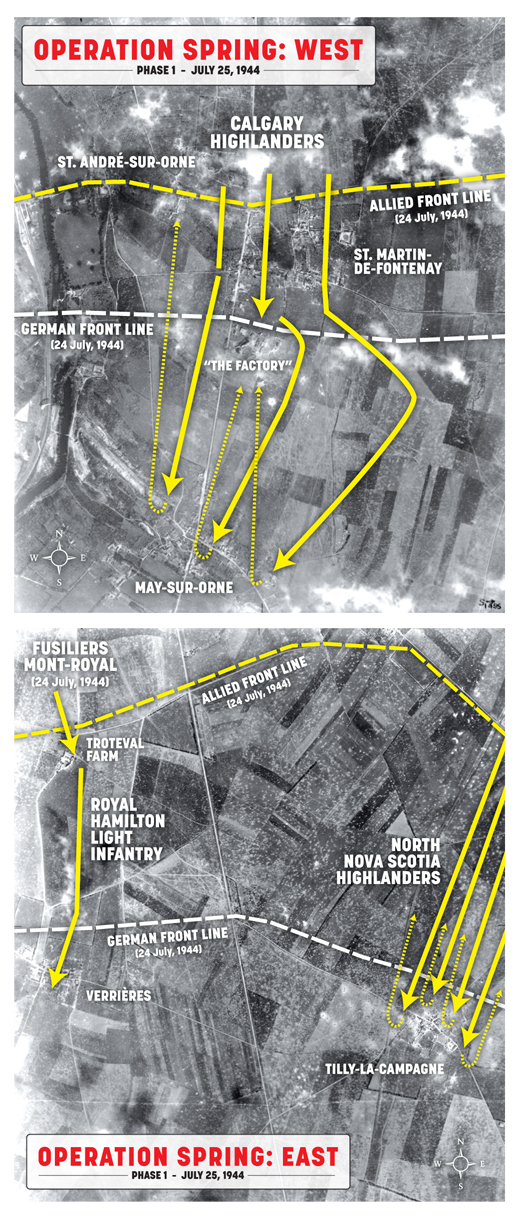

Second Tactical Air Force was to devote its full resources and artillery support was to be provided by the 2nd Canadian and 3rd and 8th British Army Groups Royal Artillery, in addition to concentrations from British and Canadian field regiments. In the first phase, 3rd Canadian Div. was to capture Tilly-la-Campagne while 2nd Div. seized May-sur-Orne and Verrières village. Phase II required 2nd Div. to capture Fontenay-le-Marmion and Rocquancourt while 7th Armd. Div. attacked Cramesnil and 3rd Div. struck Garcelles-Secqueville. These moves were to set the stage for the Guards Armoured Div. to seize the high ground around Cintheaux and the river crossings at Bretteville-sur-Laize.

Allied intelligence on enemy defences was limited by poor weather which prevented photo-reconnaissance. Prisoners of war from the 272nd and 1 SS Panzer Div. brought news of the attempted assassination of Hitler and the order of battle information, but nothing was learned about the strength or location of the battle groups of 9th SS and 2nd Panzer divisions. Intelligence officers failed to appreciate that both divisions had committed battalions to the defence of St. Andre, St. Martin, and the east-west road Simonds proposed to use as a start line.

Simonds believed a repetition of the July 19 daylight attack had little chance of success so he decided to undertake Phase I in full darkness, hoping to be past the first line of enemy resistance before daybreak. Since the enemy overlooked the area from the west side of the Orne as well as Verrières Ridge, the troops would have to wait until close to midnight before moving to their forming-up places. This meant that H-hour was delayed to 3:30 a.m., leaving less than three hours of darkness to complete Phase I if Phase II was to begin at dawn.

The Anglo-Canadian forces had very limited experience with night attacks. Second Div. had begun to study the problem in 1943. A divisional night-fighting course offered instruction in orientation and controlling troops, but everyone who has been on a night exercise in strange country knows how difficult it is to maintain direction even when no one is shooting at you. The British Army’s operational research group had devised a number of navigational aids for night fighting, but their focus was on vehicles, not marching troops. Artificial moonlight, created by bouncing searchlights off clouds, was the only practical means available in 1944.

Operation Spring was supposed to involve four divisions, but most of the troops were assigned to the later phases. The night attack involved just three infantry battalions, each committing between 350 and 400 men. This meant that the enemy—dug in with carefully prepared, interlocking fields of fire—seriously outnumbered the attackers. The corps commander, however, counted on darkness and artillery to overcome these odds.

The orders from Simonds left the divisional commanders with little latitude. H-hour had been determined and the air strikes and medium artillery program of harassing fire on known German positions were set. Major-General Charles Foulkes had to determine how best to carry out 2nd Division’s attack while two of his nine battalions were out of action recovering from their mauling in Operation Atlantic and while two others were dug in close to the enemy. Foulkes faced a difficult situation. In theory, troops held a line from St. André-sur-Orne along the road which ran on the lower slope of Verrières Ridge through Beauvoir farm to the village of Hubert Folie. In practice, this was far from the case, particularly on the right flank where the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada did not control most of St. André, never mind the adjacent village of St. Martin-de-Fontenay or the mining complex south of St. Martin. The Camerons faced continuous mortar fire, frequent enemy counterattacks and the constant infiltration of small groups of enemy soldiers. As late as the morning of July 24, a patrol of approximately 25 Germans appeared in a quarry to the left-rear of battalion headquarters. Fortunately, a section of Toronto Scottish medium machine guns was deployed in the area and the patrol was destroyed.

![CoppInset1 Silhouettes of Canadian infantry during the July 25, 1944, night attack. [PHOTO: MICHAEL M. DEAN, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA131384]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/CoppInset11.jpg)

A similar problem plagued 4th Bde. in its bid to capture Verrières village in Phase I and Rocquancourt in Phrase II. The Fusiliers Mont Royal (FMR) clung to its position at Beauvoir Farm, but Troteval Farm and the east-west road which was to serve as the start line were contested under direct fire from 1SS Panzer Div. The FMRs were able to clear the area by midnight, but in full darkness the Germans returned to their positions overlooking the road. Lt.-Col. John Rockingham, who had been rushed to France to command the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI) after Lt.-Col. Denis Whitaker was wounded, used his reserve company to push the enemy back, delaying the main attack.

The North Nova Scotia Highlanders were able to form up in Bourguebus village which had been cleared by British troops during Operation Goodwood. The centre line for the North Novas’ advance, the road to Tilly-la-Campagne, sloped upward across open fields of wheat and sugar beets. Darkness was the only cover and this advantage was lost when searchlights came on, silhouetting the North Novas who immediately came under fire.

Operation Spring stuttered to a start and quickly collapsed into confusion and chaos on both flanks. The North Novas fought through to Tilly, reported they were “on the objective” and began to dig in. At first light the enemy counterattacked. Lt.-Col. C. Petch “borrowed” a Fort Garry tank squadron in reserve for Phase II to help his battalion, but a hidden 88-mm gun and five German tanks “that appeared from haystacks” knocked out eleven Fort Garry Shermans.

The situation on the right was equally desperate. The Calgary Highlanders “man effort” force, Major John Campbell’s A Company and Major Cyril Nixon’s B Company, were lined up east of the St. André-sur-Orne/May-sur-Orne road. A Company on the left “discovered the area was not clear” and “had to fight to get on the start line.” Major Campbell had to choose quickly between detaching men to deal with this opposition or pressing on to May-sur-Orne with the supporting barrage. He chose to keep his men moving, “leaving enemy behind in slit trenches and dugouts who later on were to fire on us to our cost.”

Campbell’s men advanced towards the eastern edge of May-sur-Orne and then informed battalion headquarters they had reached their objective. The artillery continued to pound the village with some shells falling short on the men waiting on the sloping field. According to Lieut. R.L. Morgan-Dean, the company stayed there “only about fifteen minutes.” He told the historical officer who interviewed him four days after the battle that “light was breaking and our artillery remained on the objective. There was no area between the position we had reached and our final consolidation position where we might have set up a proper defensive area. Hence we came back and took up position to the right [east] of St. Martin.”

Campbell, who had lost his wireless link, was unable to report to battalion headquarters. Foulkes and Simonds and Brigadier W.J. Megill all believed A Company was on its objective.

B Company met machine-gun fire the moment the start line was crossed. Fire from a German outpost at the sunken Verrières road dispersed the company and the commanding officer, Major Nixon, was killed. Two of the platoons were forced to ground “after meeting enfilade fire from eight machine guns in St. Martin.” The third platoon, commanded by Lieut. John Moffat, was on the left flank and continued south, arriving at a “waterhole on the eastern edge of May-sur-Orne.” The village was still being shelled by Allied artillery “which came in so low” men had “to take shelter from it in dead ground.” When the barrage stopped, Moffat set off to recce the crossroads at May-sur-Orne. “As first light came we saw three Tiger tanks and two SP (self-propelled) guns. Just along the south side of the road” to Fontenay. Moffat decided that “the objective was held by too strong a force for 20 men and one PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank gun) to contest.” They proceeded “slowly and carefully” back towards St. André and met men from A Company “who told us the rest of our company was in the area just east of the factory. C Company waited out the darkness, reaching the quarry north of May-sur-Orne at 7 a.m. They too reported reaching the objective. Megill, commanding 5th Bde., believed the Calgaries had reached their objective and were presumably consolidating on it. Divisional and corps message logs show Foulkes and Simonds had the same information.

The Calgary attack on May-sur-Orne yielded roughly 100 prisoners and inflicted other casualties, but its objective remained in enemy hands. The forming-up area for the Black Watch, never mind their intended start line, was still dominated by German mortar and machine-gun fire. This was the result of divisional headquarters’ failure to recognize that St. Martin and its factory area were well-organized, strongly held positions.

Today, military training manuals emphasize what is called “C3”: command, control, and communications as the key to successful operations. Apart from the jargon, the concept appears obvious to veterans of 5th Bde. The difficulty is that command and control are not possible without communication and in 1944 infantry companies frequently lost touch with their battalion headquarters and each other. Quite apart from casualties suffered by platoon and company signals sections, the back-packed No. 18 communications set was subject to interference and frequent failure.

The RHLI attack on Verrières resulted in a very different outcome. Despite a 30-minute delay, the battalion advanced—three companies up—to obtain the widest possible frontage. The objective, Verrières village, was just below the crest of a ridge less than 1,000 yards away across level ground. The village marked the boundary between 1st SS Panzer Div. and 272nd Div. and was held by elements of a Panzer Grenadier battalion with tanks and assault guns in reserve. If the RHLI could take the village, the enemy would have to come at them over the ridge, exposed to anti-tank guns and observed artillery fire.

The battalion’s right flank company was “pinned by the intense fire” and only one platoon made it to the first objective, the hedgerow 300 yards north of the village. Despite the darkness, confusion and losses that left the platoon with just nine men, the Canadians were able to clear their section of the hedgerow, merge with the reserve platoon, and send two groups—each commanded by a corporal—forward into the village.

B Company in the centre had a far easier time. With both flanks protected, the men reached the hedgerow, overwhelmed the defenders and began to clear the houses east of the crossroads. On the left, close to the Caen-Falaise highway, enemy tanks poured fire on D Company, killing the commanding officer, Maj. G. Stinson, and his non-commissioned officers. At dawn the attached troops from 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, which had come forward to positions near Troteval Farm, engaged the German armour silhouetted on the high ground east of Verrières. The enemy tanks were well within the killing range of 17-pounders and four Panzers were destroyed. Rockingham was everywhere, inspiring his men. He brought his reserve company and carrier platoon up to the hedgerow to provide all-around defence and a mobile reserve. By 7:50 a.m., he was confident the battalion was “firm,” and reported this to headquarters.

By early morning on July 25, both divisional commanders and the corps commander had been informed that all three battalions had reached their Phase I objectives. Orders to begin Phase II were issued at 7:30 a.m., and we’ll examine the consequences of that in the next issue.

Email the writer at: writer@legionmagazine.com

Email a letter to the editor at: letters@legionmagazine.com

Advertisement