![Canadian soldiers move into Bretteville, France, June 20, 1944. [PHOTO: FRANK L. DUBERVILL, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA133732] Canadian soldiers move into Bretteville, France, June 20, 1944. [PHOTO: FRANK L. DUBERVILL, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA133732]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/CoppLead.jpg)

On June 7, 1944, D+1, the 12th SS Hitler Youth Division blocked the Canadian and British advance to Carpiquet and Caen by committing the tanks and infantry of Kurt Meyer’s 25th Panzer Grenadier Regiment to battle. It was a tactical victory with enormous operational consequences. Sepp Dietrich, the commander of 1st SS Panzer Corps, who was supposed to launch a powerful counterattack against the Allied bridgehead in Normandy with three armoured divisions, found that both 21st Panzer and 12th SS were heavily engaged and could not be withdrawn. Panzer Lehr, the third armoured division, was also being drawn into combat with British 30 Corps.

T he best that Dietrich could do was to try and dislodge the Canadian 7th Brigade which had seized ground astride the Caen-Bayeux highway and then try and split the beachhead using whatever armour was available. Thus on June 8-9, 26th Panzer Grenadier Regt. staged a series of attacks on the 7th Bde. in an attempt to secure a start line for the main attack. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, who were left with an open flank when 50th British Div. was unable to reach its objectives, lost control of Putot-en-Bessin, but it was quickly recovered when the Canadian Scottish Regt., with artillery support and the tanks of the First Hussars, overwhelmed the enemy and recaptured the village.

The Regina Rifles, holding the eastern part of the brigade fortress, deployed their four companies in separate concentrated positions with all-around fields of fire. Using battalion weapons and artillery directed by 13th Field Regiment’s forward observation officers, the Reginas beat off a series of attacks, maintaining control of the Caen-Bayeux highway.

Stung by heavy casualties and frustrated by their inability to dislodge the Canadians, the 12th SS gambled on a last attempt to seize the village of Norrey-en-Bessin. A company of Panther tanks raced towards Norrey, crossing in front of a 17-pounder “Firefly” tank of the First Hussars. With their sides exposed the Panthers were targets in a shooting gallery. The lead tank was hit and then as fast as the load-fire sequence could be done six more Panthers were destroyed.

The historian of the 12th SS later noted that Norrey “together with Bretteville, formed a strong barrier blocking the attack plans of the Panzerkorps. Repeated attacks failed because of insufficient forces, partly because of rushed planning caused by real or imagined time pressures. Last but not least, they failed because of the courage of the defenders which was not any less than that of the attackers.” The Hitler Youth were forced to dig in and admit that the “little fish,” that Kurt Meyer had boasted his men would push back into the sea, were firmly ashore and building strength.

By the evening of June 9, the Allies had linked up their four eastern beachheads and were confidently moving to close the gap between the “Utah” and “Omaha” areas. General Bernard Montgomery, acknowledging the extent of German resistance in front of Caen, now proposed a pincer movement around the city with the 1st British Airborne dropping behind Caen to complete the encirclement. This scheme was far too ambitious, and intense German attacks on the bridgehead over the Orne to the east of the city foreshadowed the failure of the left wing of the pincer. The assault on the right wing involved an attack by the 7th Armoured Div., the Desert Rats. It was to wheel around the German positions and capture Villers-Bocage, astride an important road junction. The 50th Div., holding the line to the west of the Canadians was to support the Desert Rats by an advance of its own, and the Canadians in turn were told to prepare a limited striking force to assist the British attack. Nothing went according to plan. The Queen’s Own Rifles and the First Hussars were to lead off this attack on June 12, but early on the morning of the 11th word was received that the assault was to go in that afternoon.

![Members of the Regina Rifles examine a destroyed enemy tank, June 8, 1944. [PHOTO: DONALD I. GRANT, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA116529] Members of the Regina Rifles examine a destroyed enemy tank, June 8, 1944. [PHOTO: DONALD I. GRANT, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA116529]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/Copp1.jpg)

The original plan for June 12 had called on D Company of the Queen’s Own Rifles and B Squadron of the First Hussars to capture Le Mesnil-Patry, attacking from the north through forward defences lightly manned by the 12th SS. A second Queen’s Own/Hussars battle group would pass through to seize the high ground beyond the village of Cheux. The balance of both regiments would then join their comrades “to organize a battalion fortress with armour remaining for support and counterattack.” Full artillery support was to be available. This ambitious plan could only succeed if a similar British battle group, formed by the 6th Green Howards and tanks of the Dragoon Guards, carried out a parallel advance to Cristot. Both actions were designed to assist the advance of the 7th Armoured Div. to Villers-Bocage.

This original plan might not have succeeded, but it would surely have produced better results than the hastily improvised attack ordered for June 11.

Major Neil Gordon, who commanded D Co., Queen’s Own Rifles, during the landings and at Le Mesnil-Patry, was interviewed on his experiences while recovering from wounds received in the battle on June 11. His company was in reserve on D-Day and landed after the battle on the sands that cost the Queen’s Own Rifles most of their 143 D-Day casualties. He explained that his company “came in exactly at the spot planned.…The sea wall, eight to 12 feet high, was scaled with ladders and the German machine-gun crew ran away.… D. Co. was clear of the beaches in 4 minutes.…”

On D+5, as preparations for Le Mesnil-Patry were underway, Gordon and his men were sent forward to join the Hussars. He explained that Lieutenant-Colonel R.J. Colwell, who was commanding the Hussars, “asked in vain for adequate time for teeing up the operation but was told to get in at once.” With less than two hours to prepare, there was no time for reconnaissance or even liaison with the Regina Rifles who were holding the start line. A minefield laid by the Reginas had not been lifted, so instead of a north-south advance, the battle group vehicles were forced to move single file to Norrey where at the narrow crossroads each tank made a 90-degree turn to begin an attack east to west.

Despite “rushed planning caused by real or imagined time pressures” the battle group emerged from Norrey moving into formation with two troops of tanks in the lead, reported Gordon. “The ground was open except for copses and was good tank country. The wheat in the fields was high.… All went well till they got halfway… Then machine-guns opened up from both north and south.” Gordon was hit, but stayed in control, urging the infantry “to root the Boche out.” He was then hit a second time and blanked out to wake up in a casualty clearing station.

The change in direction of the attack meant the Canadians were caught between the enemy’s forward defensive line and reserve positions. One troop of tanks continued to Le Mesnil-Patry, firing at any hedge, haystack or building that might harbour the enemy. The other lead troop reached an orchard south of the village. The remaining tanks and most of the surviving infantry remained in the wheat fields, fully involved in a firefight.

Lieut. George Bean, Sergeant Sammy Scruton, and five men from their rifle platoon also made it into the village. The intelligence officer of the Queen’s own Rifles, Lieut. R. Rae, recorded their story after the battle: “Lieutenant Bean was wounded in the leg but carried on under difficulty. Still under fire they reached the entrance to [the] built-up area and here Lieutenant Bean said to his men, ‘Shall we go in and clean it out ourselves.’ Receiving an affirmative answer, he led them through the buildings on [the] east side of town following a sunken road from which they were able to deal effectively with a considerable number of the enemy in [the] vicinity. They reached a cleared area on [the] road and men took cover in [a] large crater. Mr. Bean went forward to two of our own tanks who were firing, and was hit again this time in the back. He directed the fire of the tanks, and asked them to assist his group. On returning to his men, he was wounded for the third time and knocked to [the] ground. He waved his men on but in view of the situation the group under Sgt. Scruton decided it wise to retire and having commandeered a tank, mounted it and returned to Norrey-en-Bessin. They suffered further casualties on this trip from close-range automatic fire and grenades. Here the wounded were evacuated to the rear.”

Most of the Hussars’ tanks that made it to the village were destroyed by tank or anti-tank gunfire, but a new struggle was underway as C Sqdn. engaged the enemy in the wheat fields. The British attempt to reach Cristot had been delayed and so the 12th SS was able to turn its full attention to the Canadians, sending two companies of panzers into action.

Historian Michael McNorgan, who wrote a history of the First Hussars, notes that “the day cost the Hussars 45 fatal casualties…of these at least seven were murdered and six others listed as missing and still remain unaccounted for. A total of 37 tanks were destroyed.…” The Queen’s Own Rifles lost 98 men, 55 of them killed in action. Of the 11 riflemen taken prisoner, six were executed by the 12th SS.

The battle for Le Mesnil-Patry, “conceived in sin and born in inequity,” suggests that British and Canadian senior officers were making the same errors as their German counterparts. Hastily prepared attacks against entrenched positions such as the one held by the Reginas at Bretteville-Norrey or the 12th SS at Le Mesnil-Patry were almost bound to fail. The 12th SS, doctrinally committed to immediate counterattacks, was just beginning to learn that lesson. There is less excuse for generals Miles Dempsey and John Crocker who knew that given the vulnerability of the Sherman tank and the absolute requirement for artillery support, the odds against success on June 11 were very high.

The Canadians, with 114 fatal casualties, were no harder hit than the British forces on their flanks. The 51st Division’s 5th Black Watch Regt. lost practically an entire company “in point of fact every man in the leading platoon died with his face to the foe” at Bréville and the divisional history is merciless in its condemnation of the “hastily arranged” attacks. The 50th Div. and 7th Armoured at Villers-Bocage had also suffered severe losses.

The battles of June 10-14 marked the end of the first stage of the Anglo-Canadian assault on Caen. Montgomery now wanted time to build up his forces and he ordered Crocker’s 1st (British) Corps, including the Canadians, “to be on the defensive…but aggressively so.” The Americans were to push hard for Cherbourg while a new plan for encircling Caen was developed. Montgomery did not, in fact, renew the attack on Caen until June 26, the day Cherbourg fell. This delay was partly due to the great storm of June 19-20, but it is also clear that Montgomery was plagued by indecision, torn between his desire to apply overwhelming force to the battlefield and the fear that German reinforcements would tilt the balance in their direction.

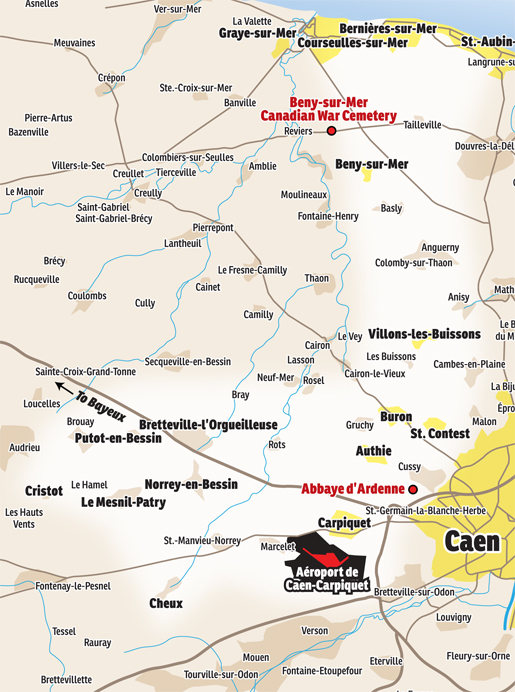

Visitors to the area will find that much can be learned from an afternoon spent in the small Norman villages where the events occurred. You may wish to retrace the advance inland by following the Regina Rifles’ route along the Mue River valley from Reviers to Bretteville-L’Orgueilleuse. Stop at the magnificent chateau in Fontaine Henry and the church-yard with its plaque to Canadian soldiers killed during the advance. Bretteville itself has changed, but the church destroyed by German artillery was reconstructed from pre-war photos. Continue east on the main street which was the Caen-Bayeux highway before the expressway was built. The landscape here is much as it was in 1944 when Panther tanks rumbled down the road to destruction.

Norrey-en-Bessin lost its church steeple and the squared off tower is a reminder of the part the village played in the unfolding drama. Plaques commemorating the Reginas and Hussars/Queen’s Own Rifles battle group are located in the small square at the crossroads where the tanks made their 90-degree turn. Follow the road west to Le Mesnil-Patry. The wheat fields remain and the footprint of the old village is visible despite the newer houses. Canadians are always welcome here, especially on the anniversary of the battle. The names of those who lost their lives are listed on a large memorial.

Putot-en-Bessin also remembers the Canadians. Plaques in the church square are informative and deeply moving. Be sure and drive to the “Bronay crossing,” the bridge at the western end of the village. From there and from the autoroute overpass you can visualize much of the 7th Bde. battle. It was one of the decisive events of the Normandy Campaign.

Email the writer at: writer@legionmagazine.com

Email a letter to the editor at: letters@legionmagazine.com

Advertisement