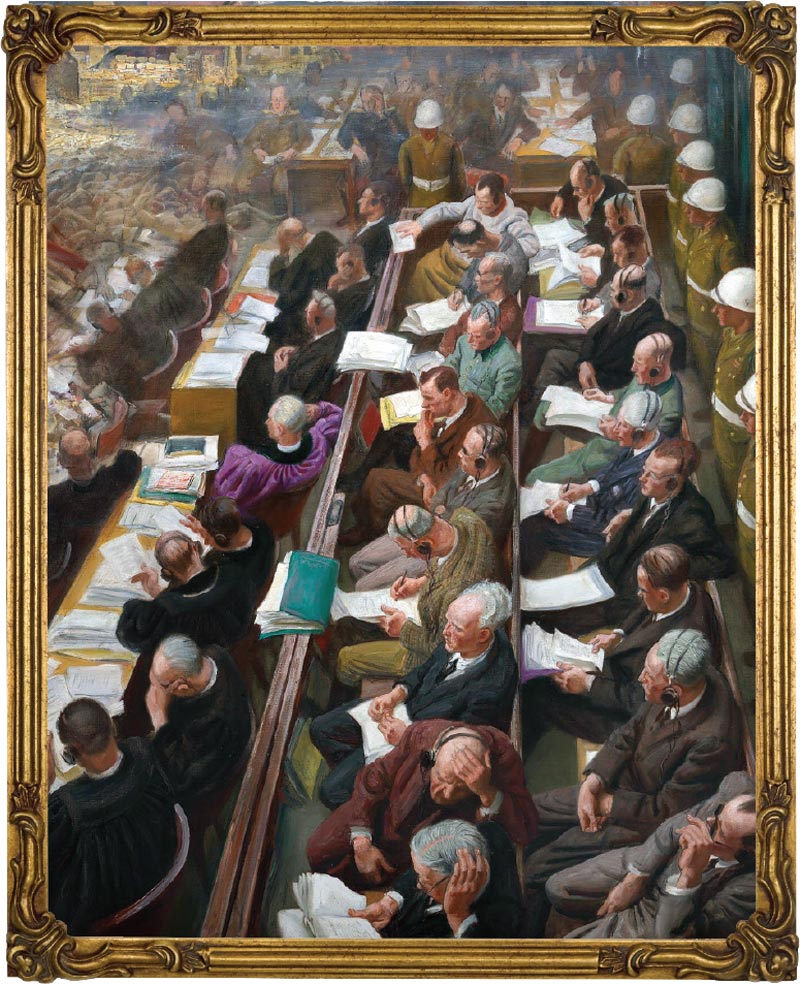

Artist Laura Knight depicts the Nuremberg Trials and the Second World War. [Laura Knight/Pictorial Press/Alamy/2h5FN4D]

Long before the end of the Second World War, Allied leaders discussed what to do about German war crimes. News of atrocities had already reached both British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. At the 1943 Tehran Conference, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin suggested executing 50,000-100,000 German officers and political leaders. Churchill was in favour of that for some of the highest-ranking Nazis, though not in the numbers Stalin wanted. In the end, the decision was made to hold legitimate trials with the accused represented by competent attorneys.

Berlin was supposed to be the site of the trials that would see Nazi leaders tried for war crimes, crimes against humanity, crimes against peace, and conspiracy to commit those crimes. But the city had been decimated by Allied bombing and, after the opening session, the trials were moved to Nuremberg, which still had a functional prison facility, and its Palace of Justice was still intact. The first of the trials began on Nov. 20, 1945.

Some of the top Nazi officials had already taken their own lives—Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler and Walter Model among them. But 24 other senior Nazis faced trial, as did dozens of others. The judges and prosecutors were chosen from Great Britain, France, the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

The trials weren’t without controversy; the Germans felt they came with a predetermined outcome and were merely show trials. And the Soviets tried to attribute their own atrocities—including the massacre of thousands of Polish officers at Katyn forest—to the Germans. There was also no appeals process for those convicted.

The trials were certainly flawed. Harlan F. Stone, chief justice for the U.S., described the proceedings as a “high-grade lynching party.” He pointed out that the German invasion of Poland was ruled a war crime, while the Soviet invasion, which was arguably more brutal, wasn’t. The French were prosecuting Germans for abusing prisoners, while they abused German prisoners awaiting trial. The Americans, meanwhile, had just killed thousands of innocent civilians in Japan.

The aim of the trials wasn’t just to bring war criminals to justice, but to act as a deterrent for future similar acts. And the trials were used to educate the German people, many of whom were unaware of the Nazi atrocities, or at least unaware of the scale. The word “genocide” had just been coined in 1944 to give a name to the Nazi slaughter of millions.

Prime Minister Mackenzie King observed the trials in person. He had visited Germany in 1937 and met some of the men who now stood accused. Hermann Göring, he noted, “had shrunk to almost half the size as I remember him.” Göring, along with 11 others, was sentenced to death, though he killed himself the night before his execution. Joachim von Ribbentrop was the first to be hanged. “I’ll see you again,” he whispered to the attending chaplain.

Ultimately, despite their flaws, the Nuremberg trials were a catharsis for a world devasted by war.

Advertisement