A 268 Squadron composite reconnaissance photograph shows the landings by the British 231st Infantry Brigade at Anselles, France, on D-Day. Note the vehicles moving away on the road from the beach.

[Eyes of the Invasion]

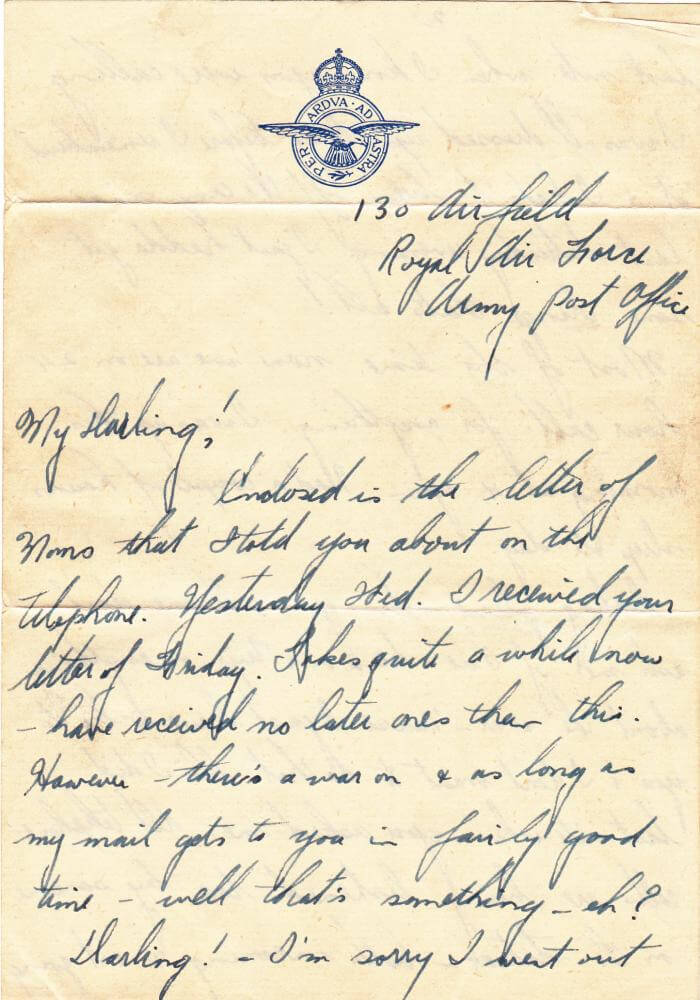

Attached to 268 Squadron, Royal Air Force, the 24-year-old Toronto native flew 37 tactical missions between May and August 1944, none more memorable than those of that stormy day in June when 160,000 Allied troops began what their supreme commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, called The Great Crusade.

“I have seen a bit of fightin’ but never have I seen such a sight as Tuesday morning!” he wrote to his newly minted bride, Marjorie. “Such an achievement—such a success! Against such odds! It was absolutely magnificent.

“Someday, the people of the world will find out what has taken place really in that invasion & what will be taking place during the next few weeks. It is absolutely astounding! I doubt if even when they know, if they’ll believe it!”

Gibson’s vivid descriptions of the epic, chaotic, fire- and smoke-filled scene were recorded as the invaders moved inland a few days after they’d hit the beaches. The landings were supported by naval and air bombardment, along with airborne troops who’d dropped in behind enemy lines under the cover of darkness.

Some 7,000 naval vessels of all types, including 284 major combat ships, supported the invasion along with more than 4,000 Allied bombers and 3,700 fighters and fighter-bombers relentlessly striking shoreline defences, inland targets and enemy aircraft.

More than 450 members of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion jumped inland before dawn on June 6 and became the first Canadians to engage the enemy on D-Day.

A few hours later, at 7:49 a.m., some 14,000 Canadian troops from the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade would start landing at Juno Beach, an eight-kilometre stretch of coastline fronting the French villages of Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer, Bernières-sur-Mer, Courseulles-sur-Mer and Graye-sur-Mer. In the coming weeks, they would push on to Caen.

Photographed shortly before D-Day, a 268 Squadron Mustang MkIA conducts a reconnaissance sortie along the French coast, photographing beaches, invasion obstacles and other targets of interest.

[Eyes of the Invasion]

“It’s a good job you didn’t know what was happening to your hubby that morning or you would have died in your bed,” he wrote. “Never! If I live to be 300 will I ever forget that 5 hours on Tuesday morning! Never have I seen, and never again will I see such a magnificent achievement—Such a show! Such a hell on earth!—as I saw between 5 o’clock & 10 o’clock that morning.

“Never again will I be so scared!!”

While an invasion was known to be imminent—and had already been delayed 24 hours by weather—Gibson said the pilots knew nothing about it until the evening of June 5, when they were briefed and the detailed plan was unveiled.

He hit the sack at midnight but never slept a wink. “I just lay there & thought & prayed & shook. I think everyone did,” he wrote. “We were called at 3 a.m. Had breakfast & we were in the air at 5 a.m.”

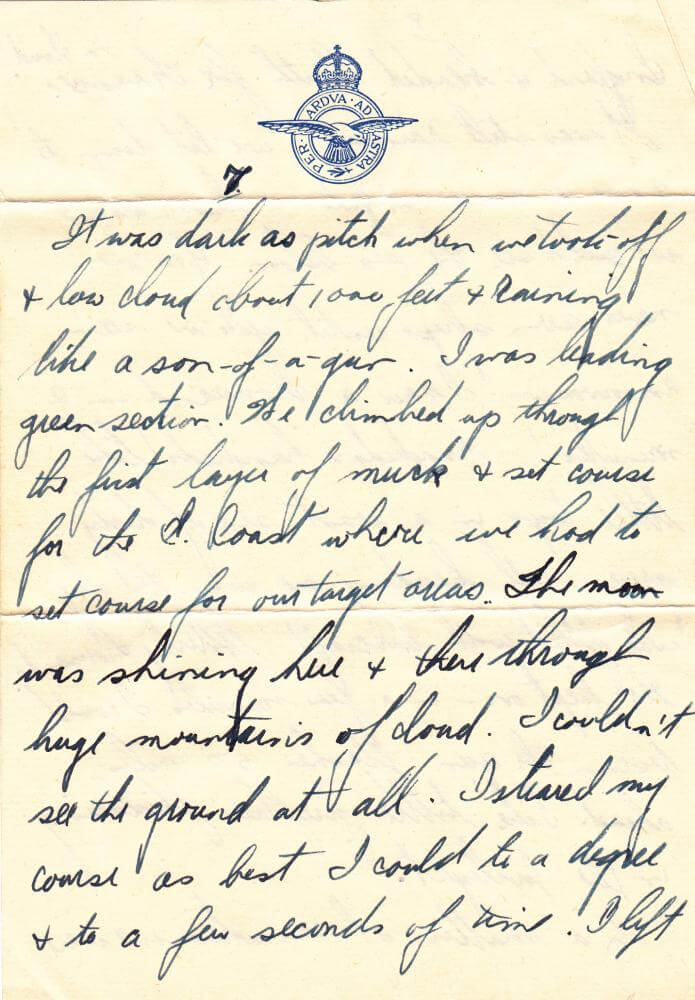

It was pitch dark with low-hanging cloud at about 1,000 feet (300 metres). It was “raining like a son-of-a-gun.” Gibson was leading green section, three planes in a triangle pattern, possibly flying in a formation of 12.

“We climbed up through the first layer of muck & set course for the E. Coast where we had to set course for our target areas. The moon was shining here & there through huge mountains of cloud. I couldn’t see the ground at all.”

[Gordon Family/Canadian Letters and Images Project]

“You’ve never seen ships until you’ve seen an invasion! I saw a thousand in 2 minutes—hundred & hundreds, like little toys in a vast sea of dirty grey, all heading one way. The sky was filled with aircraft—literally thousands.”

A landing craft just launched off HMCS Prince Henry carries Canadian troops into the Normandy beaches.

[Dennis Sullivan/DND/LAC/PA-132790]

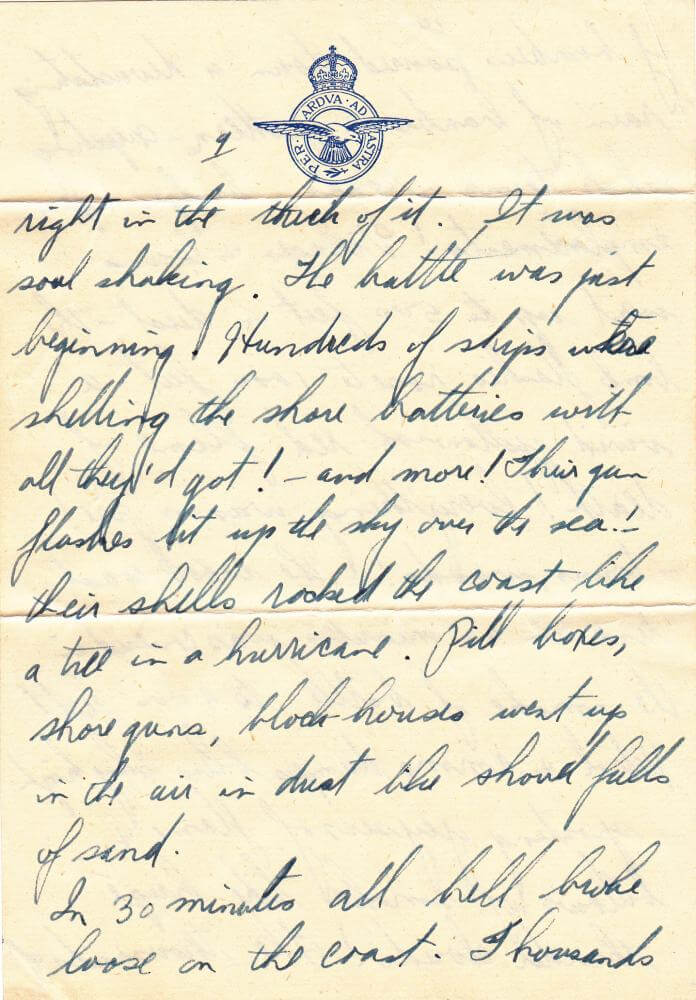

“In a matter of minutes we were right in the thick of it,” Gibson wrote. “It was soul shaking. The battle was just beginning. Hundreds of ships were shelling the shore batteries with all they’d got—and more! Their gun flashes lit up the sky over the sea! Their shells rocked the coast like a tree in a hurricane. Pill boxes, shore guns, block houses went up in the air in dust like shovel fulls of sand.

“In 30 minutes all hell broke loose on the coast. Thousands of bombers poured down a devastating rain of bombs in patterns, carpeting whole towns, roads, bridges, German emplacements! Villages & towns went up to 500 feet [150m] in dust. The bomb flashes rose to 1000 feet [350m]— a vivid yellowish-red flame of death!

“Everything was on fire—towns, woods! The whole coastline in 20 minutes was covered in the smoke of battle to 4,000 feet [1,200m]! Petrol & ammo dumps blew sky high, spouting geysers of flame & billows of smoke like huge thunder clouds!”

[Gordon Family/Canadian Letters and Images Project]

“The German gunners on shore were trying desperately to stem the terrific overwhelming flood that was overtaking them! The sky was absolutely filled with flack.”

After five minutes, he said, he was certain he would not survive another five.

“For the first few minutes I was absolutely overcome. I was stiff in the cockpit—I couldn’t speak a word over the radio! To me there was only one place where there wasn’t any flack & that’s where my aircraft was.

“But somehow when we’d finished our task for that trip we were all still intact….The whole area was covered in a pall of yellow-black smoke. The sky was aglow with fire & death. We got out & we flew back to our advanced base.”

A total of 4,414 Allied troops were killed that first day of the liberation of Europe, 381 of them Canadians.

They refueled and 45 minutes later they were off again into an “awful hail of lead.”

But as bad as the flyboys had it, Gordon noted it must have been so much worse “for the Jerries & for the boys down there in the barges.”

He was appreciating this fact when suddenly his predicament took a turn for the worse.

“At 6,000 feet [1,800m] among all the confusion my engine stopped—of all places! I called up my #2 & told him to take over & finish the job, that I was going to have to crash-land in France. I picked a field & prepared myself for the bang! Why the Jerries never shot me to smithereens, I dunno—I was a sitting target!

“By a stroke of luck or by the hand of God or something, on my last approach to the field at 500 feet [150m]I got the engine running—roughly, but running! Somehow!”

A combat-damaged 268 Sqn Mustang I awaits TLC at RAF Odiham in 1943. AM104 was repaired and later flew with 414 and 430 Squadrons, RCAF, before it was again damaged by flak near Venlo, Netherlands, in October 1944, and was finally struck off charge.

[RAF/IWM/CH10679]

A total of 4,414 Allied troops were killed that first day of the liberation of Europe, 381 of them Canadians. The Normandy campaign would go on for 76 more days.

“It was a wonderful show,” Gibson wrote. “I wouldn’t have missed it for anything. I am proud I was able to do my little wee bit to help it start on its way.”

Gibson returned to Canada at war’s end, left the air force in 1947 and rejoined in 1952, serving another 12 years. Raised on a dairy farm near Georgian Bay, Ont., he and Marjorie settled in Saskatoon where in 1964 he started what would become a local institution, Gibson’s Fish and Chips. It’s still run by the Gibson family.

Gordon and Marjorie Gibson had been married 62 years when he died in 2006. He was 85.

Advertisement