English painter Samuel Scott’s 18th century work depicts San José’s demise at the hands of the English ship Expedition at Wager’s Action off the Colombian coast in June 1708.

[Wikimedia]

The flagship in a fleet of 17 cargo vessels and naval escorts, the Spaniard was laden with an unimaginable fortune in gold, silver and jewels. The fleet was sailing from Portobelo in modern-day Panama, to Cartagena, Colombia, and on to Spain when San José was sunk during a pitched battle with an English warship.

The ship and its treasure were lost for more than three centuries, and now they’ve been found.

At the time it sailed, the War of the Spanish Succession, in which England and a European coalition were opposing Spain’s Bourbon King Philip V and his French ally, was seven years old. It would continue for another six.

The bulk of the treasure—revenue from Peru and profits from the fair at Portobelo destined for the war effort—had been loaded aboard San José and two other galleons, San Joaquín and Santa Cruz. The enemy was lurking.

“The English, as the main naval force in the anti-Bourbon coalition, were well aware of the movement of what they called the ‘Plate Fleet’ and of its importance to the Bourbon war effort,” said a May 2008 article in the journal The Mariner’s Mirror.

“Moreover, English naval officers knew that revenues from Peru and merchant profits from the Portobelo fair would make an extraordinary prize, if only they could seize it,” wrote Carla Rahn Phillips, John B. Hattendorf and Thomas R. Beall.

Cannons lie scattered among the remains of San José 600 metres beneath the ocean surface off Colombia.

[Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History]

Any attempt to take these vessels, however, would spark a major battle. And it did.

Don José Fernández de Santillán was the commodore of the Spanish fleet. Sailing under Captain General Casa Alegre, San José was armed with 64 guns and crewed by more than 600 men. San Joaquín (64 guns/500 men) and Santa Cruz (44/300), along with a French frigate (32/300) and others, were also armed and wary.

The Spaniards were almost within sight of the Cartagena harbour mouth when they ran headlong into the English squadron of Commodore Charles Wager, which had been patrolling the coast for almost three months in anticipation of their appearance.

The English flagship Expedition was a 70-gun third rate, accompanied by the 60-gun Kingston, the 50-gun Portland and the fire ship Vulture.

Expedition was Commodore Charles Wager’s flagship during operations in the West Indies between 1707 and 1709. Captained by Henry Long, it fought the Spanish galleon San José off Cartagena in 1708.

[Wikimedia]

Their sights set on the biggest ships, the English manoeuvred and Kingston attacked San Joaquín. Between an hour and a half and two hours later, San Joaquín escaped into the night.

Expedition, meanwhile, went after San José, its marines clearly intending to board. It was about 7 p.m. when, after 90 minutes of fierce, near-quarters battle, San José suddenly blew up and sank, taking its precious cargo and almost its entire crew, including the commodore de Santillán, with it.

“No one knows exactly what happened that night, or where the disaster occurred,” said the journal account, which described the inquiry that followed. “English participants on various ships later testified that San José blew up. Nearly all the Spanish testimony explicitly discounted the notion of an explosion; only one witness mentioned hearing an indistinct noise to accompany the visible fire.”

The journal article suggests Spaniards aboard the other ships were likely not positioned to witness what happened, particularly as darkness was setting in.

“The Spanish line of battle was ragged and greatly extended, probably stretching for several miles. Most of the Spaniards who testified…were far from San José, and the few men who survived the sinking said that they were on the ship one moment and in the water the next, without any clear idea of how they got there.”

The ship went down too fast for any rescue efforts, a disaster not only for the Spanish, but also for Wager, who lost what would have been one of the great prizes, if not the greatest, in maritime history. It wouldn’t be his only disappointment that night.

Hulks, like these British examples moored in Portsmouth harbour, were usually retired warships or cargo vessels stripped of their masts. They were towed by sailing ships, moored or kept dockside. They served as cargo carriers, storage facilities, accommodations, even prisons.

[Wikimedia]

The British found San Joaquín at dawn and Wager ordered Kingston and Portland to capture it. They only got off a few salvos, however, when San Joaquín and the rest of the Spanish fleet, save for the hulk Concepción, slipped into Cartagena harbour and out of reach.

The British had prevented the Spaniards from getting the bulk of the valuables to Europe, but the operation could not be declared an unqualified success.

Charles Wager became a wealthy man, but nowhere near as rich as he would have been had San José not sunk and the others not let San Joaquín get away. The captains of Kingston and Portland, Simon (Timothy) Bridges and Edward Windsor, were court-martialed for their poor battle tactics and decision-making.

The location of the San José wreck remained a mystery for more than 300 years. Testimony in the aftermath of the battle was confusing, with British interpretations of Spanish placenames often mangled and landmarks either misidentified or missed altogether in the darkness of night and fog of war.

What appears to be the bow of the Spanish galleon rises up out of the silt at the bottom of the Caribbean Sea.

[Colombian Presidency]

Spain and Peru also claimed ownership, since San José was a Spanish ship carrying wealth created by enslaved Indigenous Peruvian workers. The descendants of the Indigenous Bolivian Qhara Qhara people and enslaved Africans in New Granada, who were forced to mine precious metals, also made a claim.

After more than a decade of legal battles, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Colombian state holds the rights to items an independent third party deems “national cultural patrimony.” Anything else, it said in 2007, will be divided between the state and the U.S. salvage company Sea Search Armada.

Colombian officials claim the archeological value of the 316-year-old wreck exceeds any monetary value of its cargo.

[Colombian Presidency]

Former Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos said at the time that the ship was found in Colombian waters with the help of British maritime archeology consultants and the Massachusetts-based Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution—discoverers of the Titanic.

“This is the most valuable treasure that has been found in the history of humanity,” declared Santos.

Photographs of the ship’s distinctive bronze cannons engraved with dolphins left no doubt as to its identity. Colombia has classified its location a state secret.

In 2018, the United Nations cultural agency UNESCO intervened when the Colombian government attempted to auction some of San José’s artifacts to fund recovery costs. The Colombian government has committed $6.2 million to recovering and conserving the ship and its contents.

“Allowing the commercial exploitation of Colombia’s cultural heritage goes against the best scientific standards and international ethical principles as laid down especially in the UNESCO Underwater Cultural Heritage Convention,” said a letter from the agency to Colombian Culture Minister Mariana Garces Cordoba.

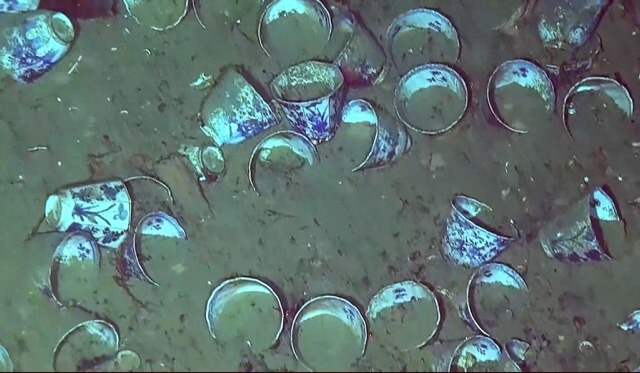

The ship’s largely intact artifacts include fine china.

[Colombian Presidency]

A recent Colombian government release said that, so far, the cargo appears virtually undisturbed and undamaged “other than that produced by the marine dynamics themselves (currents and fauna), with no evidence of external interventions.”

“There has been this persistent view of the galleon as a treasure trove. We want to turn the page on that,” said Alhena Caicedo, director of the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History. “We aren’t thinking about treasure. We’re thinking about how to access the historical and archeological information at the site.”

Few ships comparable to San José in age and archeological value have ever been recovered—England’s 500-year-old Mary Rose and Sweden’s 400-year-old Vasa come to mind—and none has ever been salvaged from warm tropical waters.

Bogotá officials planned to begin robot-driven recovery efforts this month.

Said Caicedo: “This is a huge challenge and it is not a project that has a lot of precedents. In a way, we are pioneers.”

Distinctive markings on the cannons confirmed the wreck was the Spanish galleon San José.

[Colombian Presidency]

Advertisement