A hearse leaves Canadian Forces Base Trenton after the ramp ceremony for Sergeant Marc Léger in 2002. [Reuters/Alamy/2CPDP9D]

What started as a grassroots tribute to Canada’s fallen from Afghanistan 20 years ago evolved into Highways of Heroes across the country

In the three great wars of the 20th century, Canadian soldiers were buried in the countries where they died. Since 1970, Canadian military personnel who died abroad have been brought home for burial—mostly unnoticed by the general public.

But the war in Afghanistan produced a steady stream of caskets that didn’t go unheeded or unheralded.

The 158 Canadian Armed Forces members who died in Afghanistan were flown to 8 Wing, Canadian Forces Base Trenton in Ontario where a ramp ceremony was performed. Then they were transported some 170 kilometres west on Highway 401 to the morgue in Toronto.

A flag waves as the procession for Corporal Nathan Cirillo passes on Ontario’s Highway of Heroes in 2014. [Performance Image/Alamy/E9D1DX]

The repatriation ceremony for the first four soldiers—Sergeant Marc Léger, Corporal Ainsworth Dyer and privates Richard Green and Nathan Smith—all killed on April 17, 2002—was broadcast live from the base and, like a flash, word of the funeral procession spread.

Veterans, military personnel, firefighters and police, and their families living near Highway 401 headed for overpasses near their communities to pay respect to the soldiers and their families.

Pete Fisher, a journalist in Cobourg, Ont., heard about the motorcade from his father, a retired firefighter. Fisher alerted the local emergency services dispatcher and headed for the highway with his camera to document the impromptu display of support and patriotism.

“It’s a feeling hard to describe,” said Fisher. “People wanted to show their support [and] let the families of the fallen know they weren’t alone.”

That message was clear to Don and Laurie Greenslade of Saint John, N.B., as they travelled the route in 2007, escorting the body of their son, Private David Robert Greenslade, Royal Canadian Regiment, who was among six Canadian soldiers killed Easter Sunday that year in Afghanistan.

Corporal Jordan Kowalski salutes as the cortège for Trooper Marc Diab passes along Ontario’s Highway of Heroes in 2009. [Carlos Osorio/Getty Images/165282818]

“It was overwhelming,” said Don. “Seeing the signs, and the people, the flags, the support…it is hard to explain the feeling.

“My son will never be forgotten.”

As the war dragged on and more motorcades wended their way down the highway, great numbers of people flocked to overpasses to participate in what became an unofficial rite. They were often dressed in red and carried Canadian flags or flags of the soldiers’ home provinces.

People had “the desire or need to feel a sense of belonging to the national group in a time of national crisis,” wrote Tracey Raney in, “Patriotisms of the People: Understanding the “Highway of Heroes” as a Canadian National Landmark,” a chapter in Landscapes and Landmarks of Canada: Real, Imagined, (Re)Viewed.

The ceremonies gave Canadians a way to express patriotism in a way that transcended their differences, she wrote. One participant even waved the Quebec flag, telling Raney, “because you just don’t see them around here…I’m trying to show the families that we all care.”

“The highway bridges became spaces upon which Canadians could collectively grieve the war losses of the ‘Canadian’ national family in a way not seen before in Canadian history,” wrote Raney, a professor at Toronto Metropolitan University.

In 2007, journalist Joe Warmington coined the phrase “Highway of Heroes” and that summer naval reservist James (Jay) Forbes gathered more than 65,000 signatures on a petition in a successful campaign to have Ontario officially rename the 172-kilometres of the 401 between Trenton and Toronto the Highway of Heroes.

Ontario’s Highway of Heroes is only the first leg of the journey for military personnel en route to burials in hometowns across the country. In what Raney dubbed “grassroots patriotism,” gradually all provinces and the Northwest Territories named their own Highway of Heroes, though in Alberta it’s known as Veterans Memorial Highway and in Quebec as Autoroute du Souvenir (Remembrance Highway).

These thoroughfares serve as permanent memorials to the country’s soldiers, sailors and air crew. But the idea of a national memorial highway in Canada stretches back more than a century.

There was a time in Canada when highways did not run…well, together.

Civic leaders thought that just as Confederation had been the driving force behind the construction of a railway crossing the continent, so too, could the First World War inspire a national project: a memorial highway uniting the country.

In March 1916, the Canadian Municipal Journal floated the idea of a transcontinental artery that “would be a national monument to Canadian faith and virility.” The following year, the journal expanded on the idea: the project could provide employment for returning soldiers and people who lost their jobs as war industries shuttered; it could link cities and provinces and attract tourists; and it would allow access to untapped natural resources.

“Such a highway would be the best monument that the people of Canada could build in memory of those splendid sons who have given their lives in her cause on the fields of Flanders. Such a road would be a real peace monument,” a reminder to following generations “that Canada had done her duty at this time of democracy’s trial.”

In 1918, the journal exhorted Canadians to think about postwar reconstruction. The “3,500 miles [5,600 kilometres of highway] to link up the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans would cost in round figures $75,000,000.” (The equivalent of more than $125 billion today.) “A huge sum, but none too large for such a purpose.”

But a country in mourning, vowing the sacrifice would never be forgotten, and with no gravesites to visit, favoured permanent memorials carved from stone or wrought of metal, incised with names of the dead and, often, the battles in which they fought. In communities across the nation monuments large and small were commissioned by ordinary folk, churches and local organizations, schools and businesses.

Canada and the Dominion of Newfoundland erected larger memorials in Europe on the grounds where their soldiers fought, died and were buried. The Canadian National Vimy Memorial was dedicated in France in July 1936 and the National War Memorial was unveiled in Ottawa in 1939.

Some communities took a more pragmatic approach, founding memorial universities, high schools and hospitals, gardens and roads. But there was no national com-

memorative highway. Construction on the Trans-Canada Highway started after the Second World War and was largely completed in the 1960s. It was not named a memorial,

but it is a symbol of national unity.

“People wanted to show their support [and] let the families of the fallen know they weren’t alone.”

Although the original Highway of Heroes is in Ontario, many Canadians consider it a national memorial—the body of every serviceman and servicewoman travels it on the initial part of the journey to his or her hometown.

In November 2011, Master Corporal Byron Greff, who had served with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, travelled the Highway of Heroes, the 158th—and last—Canadian soldier repatriated from Canada’s war in Afghanistan.

But the Trenton to Toronto stretch of the freeway continues as a functional memorial, and people continue to crowd the overpasses as funeral processions go by, doing so even during the pandemic.

In 2020, one Ontario veteran drove more than two hours to spend 15 seconds in silent reverence for the passing funeral procession of a CAF member killed in a helicopter crash off the coast of Greece.

“I am here in respect of the dead soldiers,” said veteran Maggie Van Tassell in an interview with Fisher. “There is family and friends back in Nova Scotia and all over Canada that can’t be here. So you have to be here for them.”

Ontarians continue to be there for the highway, too, cleaning and beautifying it.

The Highway of Heroes offers Canadians a physical space to collectively express their ʻCanadianness,’ remarked Raney. “The public’s response to Canadian military war deaths in Afghanistan was deeply connected to a sense of national pride, identity, and belonging to the Canadian nation.”

Ontario’s Adopt-a-Highway program was established to encourage local groups to gather to clean up the shoulders of provincial roads. In 2016, Kerri Tadeu, Corporal Nick Kerr and retired Master Corporal Collin Fitzgerald adopted 1.2 kilometres on the Highway of Heroes in honour of Tadeu’s friend Major Michelle Knight-Mendes who died in Afghanistan in 2009. In 2017, they spent 21 days cleaning the section.

“We then had the idea to adopt the entire 172 kilometres of the Highway of Heroes,” Tadeu said in an interview with Fisher. Since 2017, twice annual cleanups have been organized along the route.

During the last five years, the volunteer pool has grown to include community and youth groups, Royal Canadian Legion branches, police, fire and emergency personnel, as well as veterans and serving members of the military. Together they’ve collected thousands of bags of garbage.

Although the focus is cleaning up the space, it also provides veterans an opportunity to connect in common purpose, which contributes to their mental health said Tadeu, a psychiatric nurse.

“I feel humbled that one of the unnamed trees planted as part of the project will be for me,” said one Afghanistan veteran.

Thousands of volunteers, including members of the CAF and Legion branches, have also helped plant trees along the Highway of Heroes during the last seven years, said Mark Cullen, chair of the Highway of Heroes Tree Campaign.

In 2014, as Canada’s Afghanistan mission was winding down, it was suggested at a meeting Cullen chaired that trees should form a living tribute along the memorial freeway. It took a year to raise money to start buying trees and organize volunteers to plant them. Donations eventually topped more than $10 million, and future contributions will support their preservation.

The tree project grew from an initial campaign to plant 117,000 trees along the highway right-of-way to commemorate every life lost during service in the CAF since Confederation. It has since expanded to planting nearly two million more trees—one for every Canadian who has ever served.

A ceremony for planting the last of the trees is planned prior to Remembrance Day 2022. (Up-to-the-minute information about public events can be found on the website www.hohtribute.ca.)

“I feel humbled that one of the unnamed trees planted as part of the project will be for me,” said Afghanistan veteran Kerr in a 2019 interview.

“I think of the eight friends I lost on the battlefield every time I volunteer,” said Kerr, who helped plant trees for three years. “Every time I put a tree in the ground, I think, ‘That one is for you, buddy.’”

The idea to plant trees along a memorial road also dates back a century.

Calgary is one of many communities that dedicated a commemorative road after the First World War (see sidebar “Service roads,” right). The city renamed a stretch of street running along the north bank of the Bow River as Memorial Drive. Beginning in May 1922, the first of 3,278 trees, mostly poplars, was planted, honouring each of the local war dead.

It was meant as a living memorial and solace for families who did not have a grave to visit. Metal discs bearing donors’ names were originally attached to stands by the trees. Over the years the roadway has expanded, necessitating the removal of some trees. The wide swath of wood shrank in places to a narrow ribbon of trees along the bank of the Bow.

Now that the poplars planted a century ago are reaching the end of their lives, a city revitalization of the area has cloned the original trees to provide replacements, a rededication to remembrance.

A new generation of Calgarians has been introduced to commemoration by the revitalized space, which includes the Calgary Soldiers Memorial, the public space in Poppy Plaza and, of course, hundreds of preserved and replanted memorial trees.

Canada’s network of Highways of Heroes continues to provide solace to families who lost loved ones in service to their country.

“Every day we drive down the B.C. Highway of Heroes I blow a kiss to commemorate my Father and Father-in-law, both WWII Veterans, my Son the Afghanistan War Vet & all the boys & girls who have died for our country & who are still protecting our country,” the parent of one veteran posted on the B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure webpage devoted to its memorial freeway.

Said Fisher succinctly of such paved tributes: “If it gives just .01 per cent of solace to a grieving family, the effort is worth it.”

Service Roads

Across the country, communities small and large have memorialized their local servicemen and servicewomen by naming streets in their

honour. Here’s a national selection of such tributes.

Has your hometown done so, too? Share your

street-name story with Legion Magazine on Twitter

(@Legion_Magazine) using the hashtag #serviceroads.

British Columbia

In Richmond, 61 streets have been named in commemoration of local soldiers who died in military service.

Alberta

Sergeant Shane Stachnik Drive in Waskatenau, population about 250, commemorates the combat engineer killed in Afghanistan in 2006.

Saskatchewan

Fulton Drive in Regina commemorates Royal Canadian Air Force pilot Captain Gary Fulton, who died May 31, 1976, after a duck was sucked into the engine of his Tutor jet. Fulton guided his plane away from a residential area to crash land in a park.

Manitoba

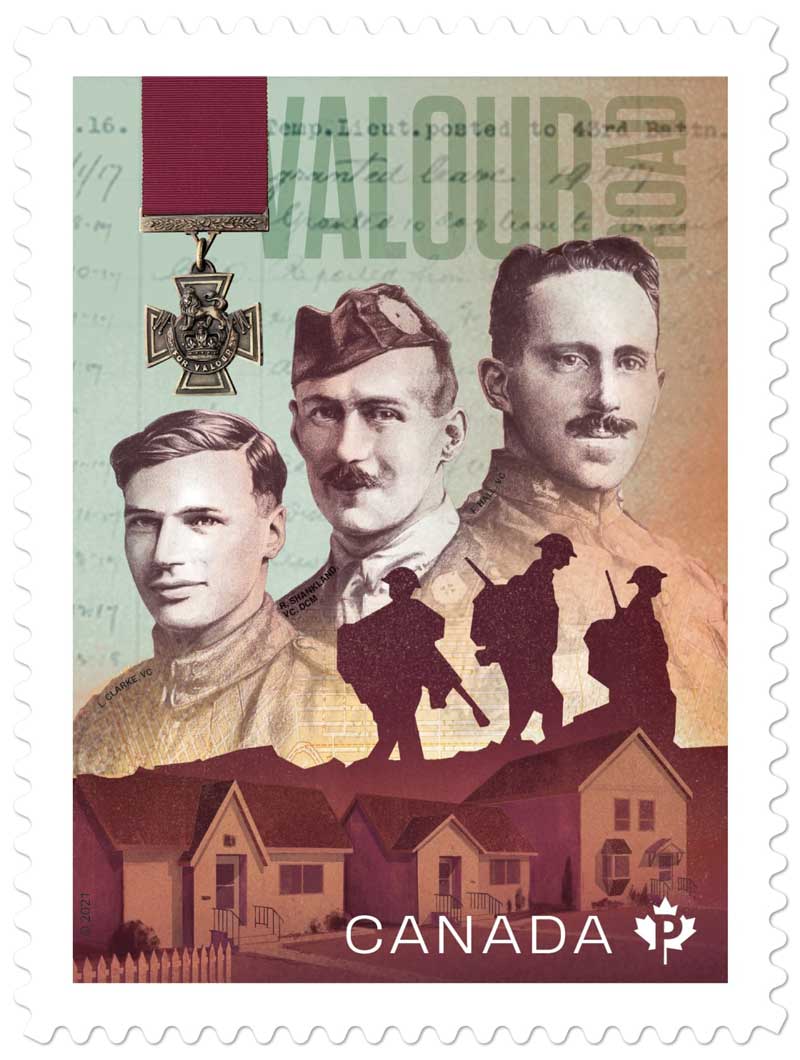

In 1925, Winnipeg renamed Pine Street to Valour Road to commemorate First World War Victoria Cross recipients Leo Clarke, Frederick Hall and Robert Shankland, all former residents of the street.

Ontario

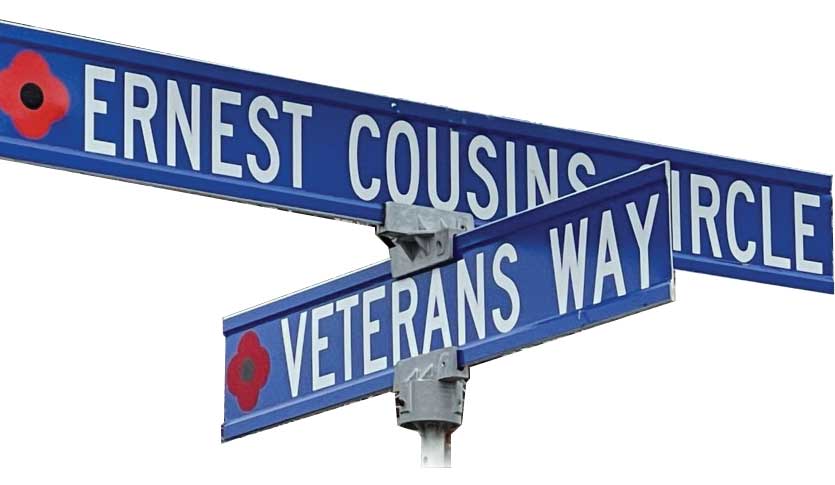

In Newmarket, Veterans Way intersects with Ernest Cousins Circle, named for an infantryman who died in the First World War. It is one of a dozen local streets named in honour of residents who served and died in the military.

Quebec

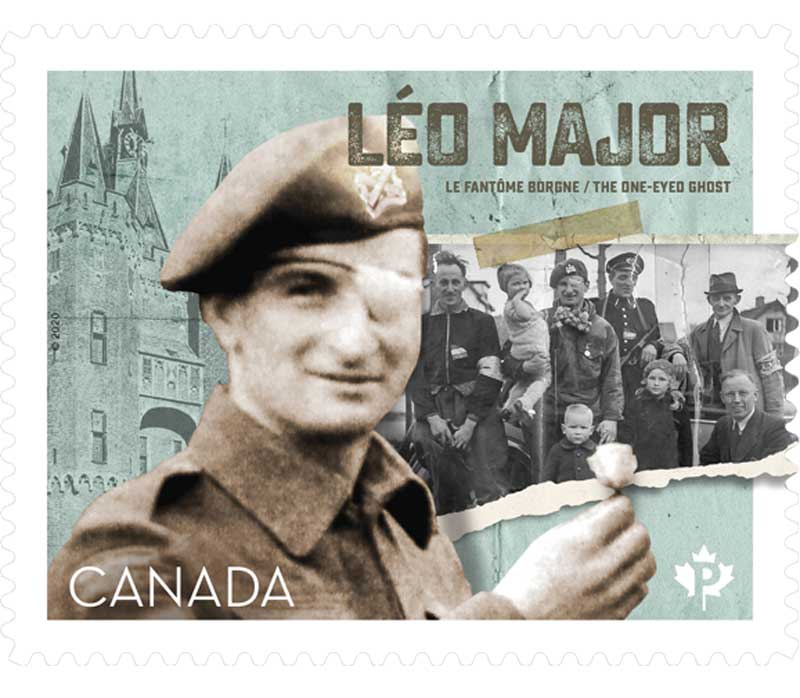

In 2021, Quebec City renamed a 3.4-kilometre segment of road near 2nd Canadian Division Support Base Valcartier to Route Léo-Major, after the only Canadian to earn Distinguished Conduct Medals in two different wars (Second World and Korea).

New Brunswick

Bravo Landing in Saint John commemorates a local soldier and five comrades killed in Afghanistan in 2007. Six maple trees planted along the street honour the men: corporals Aaron E. Williams and Brent Poland, Sergeant Donald Lucas, Master Corporal Christopher Paul Stannix and privates Kevin Kennedy and local David Greenslade.

Nova Scotia

Montague Street in Lunenburg commemorates Lieutenant-Colonel Montagu Wilmot, commander of the Fort Cumberland garrison during the Seven Years’ War.

Prince Edward Island

Some believe Plug Street in Malpeque was named by Corporal George Ellwin Champion to commemorate islanders who fought and died in the Great War. The name reportedly originates from Ploegsteert in Belgium, near Ypres.

Newfoundland

Pynn Place in St. John’s commemorates Henry Pynn who fought in the Irish Rebellion in 1798 and the Napoleonic Wars. In 1815, he became the first native-born Newfoundlander to be knighted.

Northwest Territories

Part of Distributor Street in Inuvik was renamed Veteran’s Way in 2007 in honour of Canadians who’ve served.

Yukon

The territory’s portion of the Alaska Highway was officially dedicated to all veterans in 2012.

Advertisement