JOHN HUGHES-HALLETT

JOHN HUGHES-HALLETT[Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Just after 1 p.m. on Aug. 19, 1942, Captain John Hughes-Hallett stood on the bridge of HMS Calpe—Operation Jubilee’s command destroyer—and ordered the last naval vessels to abandon attempts to rescue soldiers from the embattled Dieppe beaches.

As the ships turned toward Britain, the disastrous raid’s chief architect watched blood streaming from their scuppers. Afterward, Hughes-Hallett admitted that the navy had been unable “to give the troops [ashore] effective support. A number of mistakes were made, chiefly by myself.”

In December 1941, Hughes-Hallett had joined Combined Operation Headquarters (COHQ) as right-hand man to the recently appointed Commodore (later vice-admiral) Lord Louis Mountbatten. Along with his two core naval staffers, Hughes-Hallett arrived at COHQ determined to see it embark on grand raiding schemes.

Previously, Hughes-Hallett wrote, COHQ’s “tiny raids” had “achieved nothing,” while “a number of very gallant officers…lost their lives to little avail.”

The planned Dieppe and Saint-Nazaire raids kicked off the new agenda. Although Saint-Nazaire had a distinct purpose—to destroy dry docks capable of sheltering the battleship Tirpitz and damage U-boat pens—the objective for the offensive on Dieppe wasn’t as clear.

“We thought it would be interesting…to capture…a small seaport for a short time…,” admitted Hughes-Hallett later. “We were raiding for the sake of raiding.… There was no particular significance.”

For all its thoroughness, Operation Jubilee never had a chance of success.

The Dieppe Raid strategy started to coalesce in January 1942. Eventually, a 300-plus-page plan attempted to meticulously address every feasible contingency. It included precise schedules for how the mission—from beach landings and inland advance to evacuation—would be executed.

Yet, for all its thoroughness, Operation Jubilee never had a chance of success. Failure to accurately determine the strength, organization and ability of the German defenders meant that the moment the largely Canadian force reached the beaches, the scheme disastrously unravelled. From the outset, a chaotic battle at sea, in the air and ashore sought first to win beachheads, then switched to a disorganized, increasingly desperate evacuation that left the majority of soldiers ashore.

In the raid’s tragic aftermath, Hughes-Hallett, and many others—both at the time and since—sought some morsel of value to justify such loss. Hughes-Hallett believed the failed assault proved that capturing a usable port in the inevitable cross-channel invasion wasn’t possible.

Therefore, he declared, the Allies must build an amphibious port facility and tow it across the English Channel. In his 1943 role as commodore commanding the Channel Assault Force, Hughes-Hallett helped advance creation of the Mulberry harbours that ultimately proved vital to D-Day’s success.

A flawed raiding scheme was easily defeated by a robust defensive plan

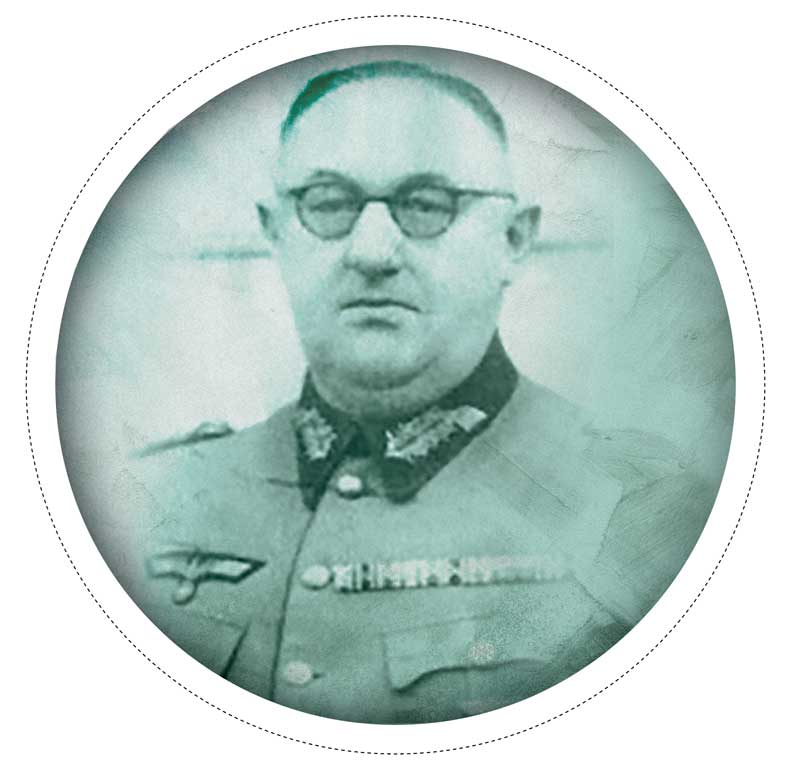

KONRAD HAASE

In April 1941, Generalleutnant Konrad Haase’s 302nd Infantry Division assumed responsibility for some 80 kilometres of coastline anchored on Dieppe.

Haase’s task was “prevention of a landing from the sea and air.” Although Haase considered Dieppe “the focal point,” he did not expect it to “be attacked directly…but rather by landing attempts at nearby points and the formation of a bridgehead.”

Haase believed the rocky cobble beach fronting Dieppe’s promenade, combined with the overlapping gun positions on heights on either side of the town, would surely convince the Allies that any frontal assault would be suicidal.

The 302nd had been created in November 1940 with troops drawn from two disbanded divisions. Fifteen French 75mm guns inherited at Dieppe seriously bolstered the German artillery complement, although mobility was very limited. But Haase had a good divisional staff and cadre of officers. Considered a static unit, he organized the division so it covered possible landing beaches without the need for reinforcement.

His preparations aimed at defeating any amphibious assault right on the beaches.

By the spring of 1942, many of Haase’s best soldiers had been sent to the Soviet front. But new recruits—particularly so-called ethnic German foreign nationals, such as Poles and Hungarians—sustained the division’s strength.

This reduction in quality did not concern Haase. Kept on a tight leash, even poor soldiers could still fight well from fixed positions and Haase expected them to fight to “the last shot.” His preparations aimed to defeat any amphibious assault right on the beaches.

“The main line of resistance—that is the coastal strip—must be firmly in possession of the troops at the conclusion of the fighting; and enemy troops that had reached the mainland must have been destroyed,” he ordered.

By mid-August 1942, the beaches were sown with thousands of mines and wire obstacles. Even though a frontal assault was not foreseen, steel doors could block all exits from Dieppe’s promenade. Anti-tank guns, artillery, mortars and machine guns covered every likely landing beach.

While the 302nd easily held its ground on Aug. 19, Haase was impressed by the tenacity of the Canadians and other raiders. They attacked, he wrote, “with great energy. That the enemy gained no ground…was not the result of lack of courage, but of the concentrated defensive fire of our divisional artillery and infantry heavy weapons.”

Yet, the enterprise baffled Haase. “It is incomprehensible that it should be believed that a single Canadian division should be able to overrun a German Infantry Regiment reinforced by artillery.”

Advertisement