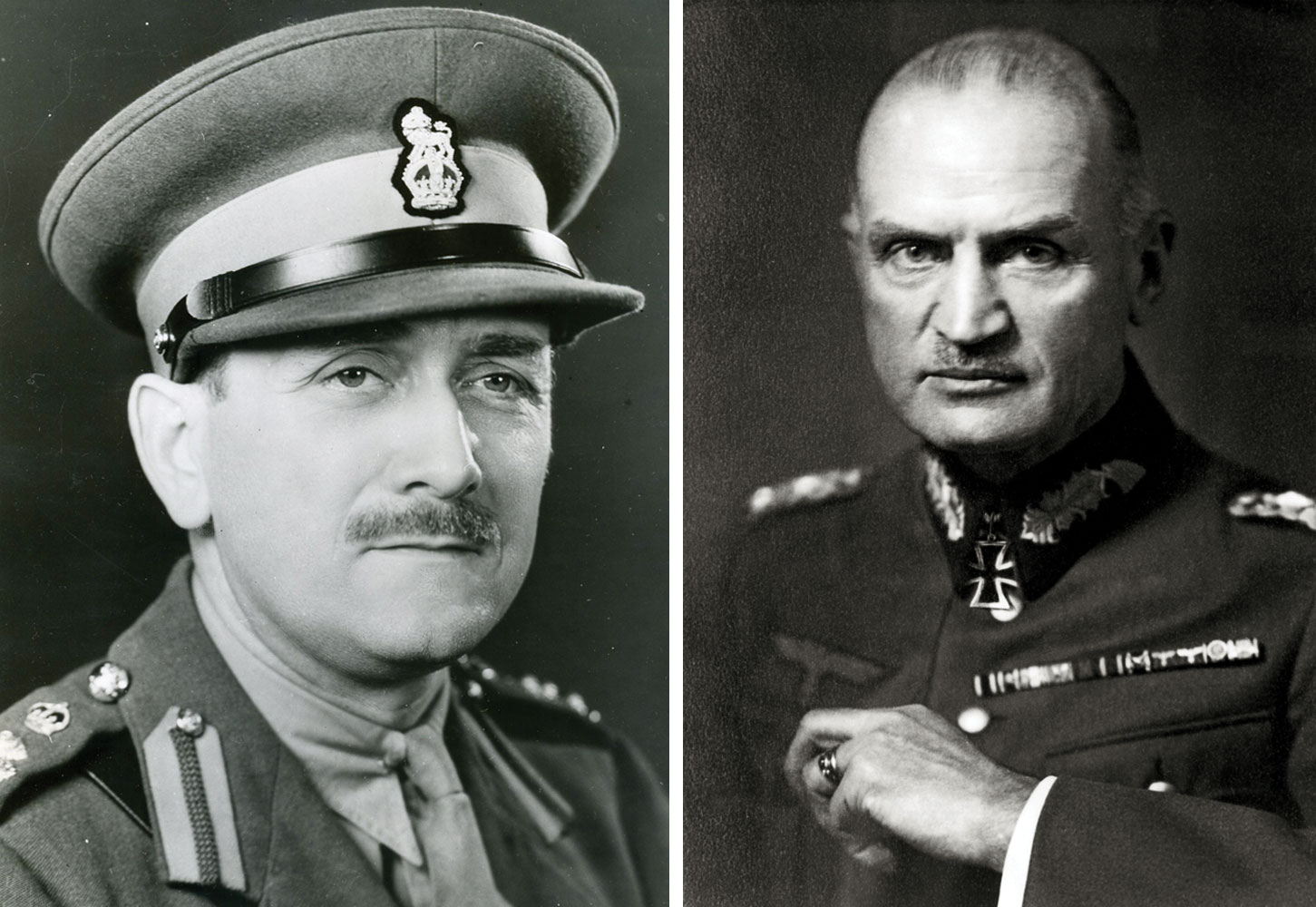

Hero: Charles Foulkes

On April 28, 1945, I Canadian Corps’ Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes—senior officer in western Netherlands—led negotiations with Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz of Germany’s 25th Army for the surrender of the 120,000-strong German garrison. With the Hunger Winter gripping the western regions still occupied by Germany, the negotiation required a twofold approach. First, convincing the Germans to stand down and enable delivery of humanitarian aid by Allied air drops and truck convoys. Second, formalizing the garrison’s surrender.

Four days earlier, I Canadian Corps had halted before the fortified Grebbe Line, held in strength by 25th Army. Both sides realized that any fight west of the line would necessitate costly urban warfare and many civilian casualties, so an informal ceasefire was agreed.

The 42-year-old Foulkes had proved as lackluster a corps commander here as he had leading the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division through the Normandy campaign. Promotion to corps command resulted more from lack of suitable candidates in the Canadian senior officer pool than ability.

“He reminded me,” said Major-General Harry Foster of 1st Canadian Infantry Division, “of someone who, knowing that he has overstepped his abilities, tries to bluff his way through.”

Negotiating the German surrender in western Netherlands did require a degree of bluff: Blaskowitz’s forces outnumbered the Canadians. In the first face-to-face negotiation, a German officer representing Blaskowitz proposed opening only one road for a few hours each day. Foulkes retorted that the idea was “ludicrous.” A sufficiently demarcated area had to be agreed, so its boundaries “could not possibly be mistaken by the stupidest man.” When the representative demurred, Foulkes snapped—“I’ve had enough!”—and demanded to talk directly with Blaskowitz. A hurried phone call yielded assurance that the ceasefire across the whole Grebbe Line front would be sustained.

Supplies soon flowed, but the surrender negotiation remained unresolved. Realizing Blaskowitz hoped the ceasefire could remain unofficial, Foulkes demanded a written agreement. On May 3, he produced a European map.

“I pointed out the ridiculousness of the [position of] 25th German Army in Holland,” said Foulkes. “I pointed out that my instructions were ‘unconditional surrender.’” His surrender terms were identical to those drafted by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

Foulkes demanded Blaskowitz sign on May 5. At the Hotel de Wereld in Wageningen, Foulkes read each condition as Blaskowitz signalled approval with a nod or saying, “Understood.” The two then signed the truce and Canada’s war in Holland ended.

Appointed Chief of the General Staff in 1951, Foulkes retired in 1960.

On April 7, 1945, Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz assumed command of Germany’s 25th Army with orders from Hitler to defend Fortress Holland to the last.

Reichskommissar Arthur Seyss-Inquart—the Third Reich-appointed governor of the occupied Netherlands—was engaged in secret ceasefire negotiations, but Blaskowitz was inclined to fight on. He ordered the Eem and Grebbe rivers breached to inundate indefensible ground north of Amersfoort.

Blaskowitz, 61, had been a professional soldier before the rise of the Nazis. After leading 8th Army through the invasion of Poland, he became the country’s military commander. His resistance to the persecution and murder of Polish Jews, however, led Hitler to sack Blaskowitz for his “childish attitude.”

Shortages of competent generals soon returned him to the command of Army Group G and then Army Group H. As Canadian operations split the German forces in Holland, Blaskowitz became responsible solely for 25th Army.

During the first weeks of April, with Seyss-Inquart negotiating directly with the Allies, Blaskowitz kept his distance. On April 17, German troops opened another dike near Den Helder and inundated Holland’s newest polder—an area of almost 200 square kilometres. Seyss-Inquart then warned that any attack on the Grebbe Line would see a major dike between Rotterdam and Gouda breached—yielding massive flooding north to Amsterdam.

As negotiations on providing aid to the Dutch progressed, Blaskowitz sent emissaries to represent him at proceedings on April 28. Two days later, he sought assurance from Canadian Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes that he was not on any Allied war criminal list. After consulting with Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, Foulkes reported Blaskowitz was on no lists.

On May 1, Generalleutnant Paul Reichelt—Blaskowitz’s chief of staff—offered Foulkes a guarantee that no German soldiers would inhibit the food deliveries. But on May 3, Reichelt said Blaskowitz was determined to fight on for fear that 25th Army would be sent to Russia as slave labour if he surrendered it.

“This annoyed me,” said Foulkes. “I told him there was no intention of putting the Germany Army into Russia.” If, however, the Germans flooded more of Holland, “they would be war criminals…and…punished accordingly.”

Taken aback, Reichelt promised that Blaskowitz was agreeable to surrender on an undertaking from Foulkes that “they would

not be sent to Russia.” Foulkes agreed.

After five hours working through the conditions on May 5, Blaskowitz signed the surrender. Later arrested on trumped-up Russian charges, Blaskowitz jumped to his death on Feb. 5, 1948—the day his Nuremberg trial was to begin.

Advertisement