On Feb. 8, 1937, some 150,000 Spanish civilians fled Málaga

and General Francisco Franco’s closing Nationalist forces.

Confined to a narrow coastal road, the refugees

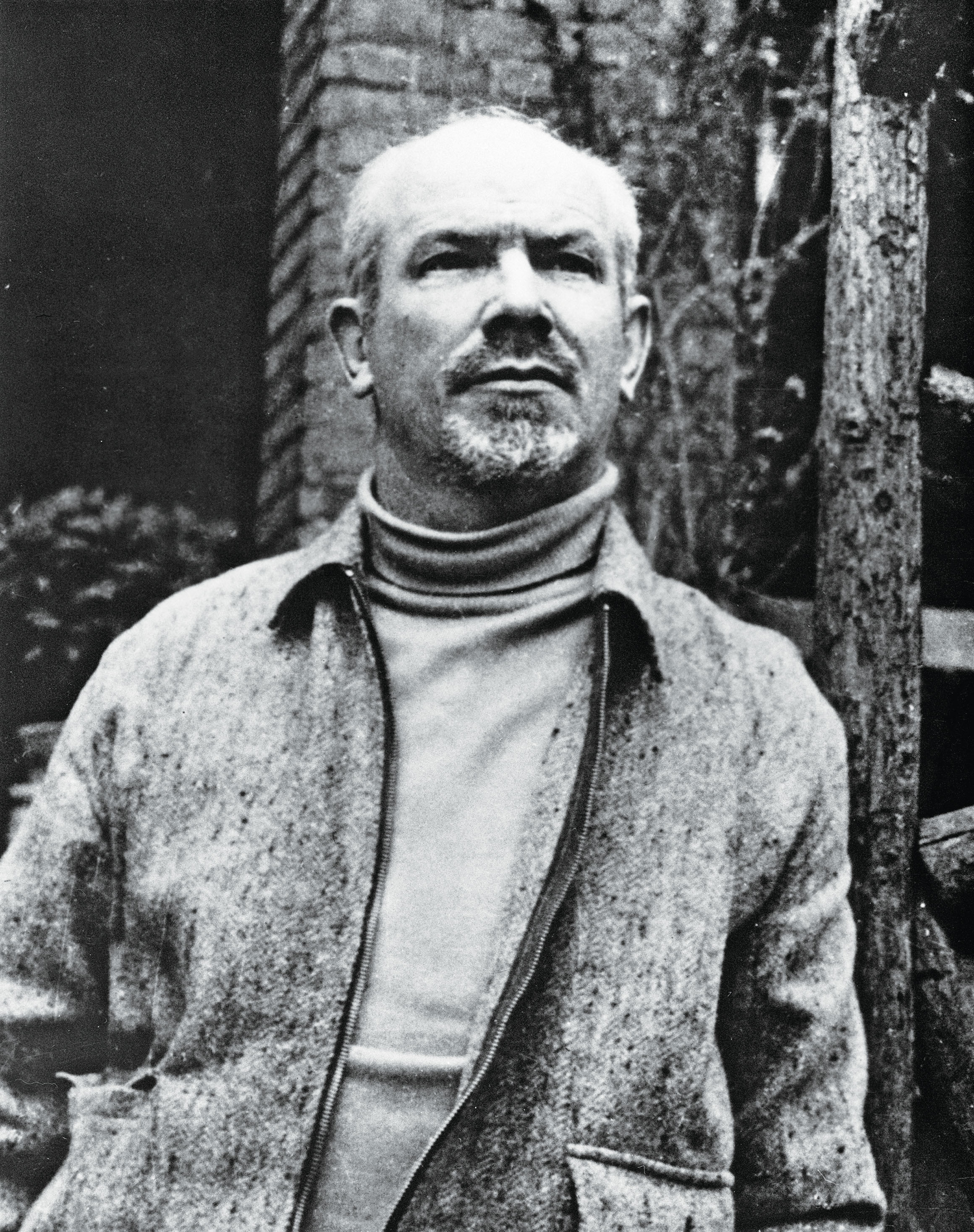

soon met Canadian doctor Norman Bethune

Norman Bethune, the 46-year-old former chief of thoracic surgery at Montreal’s Sacré-Cœur Hospital, arrived in Spain on Nov. 3, 1936, as the head of a medical unit dispatched by the Canadian Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy. Bethune was convinced that international fascism sought to dominate the world.

“They’ve begun in Germany, in Japan, now in Spain and they’re coming out in the open everywhere. If we don’t stop them in Spain while we can, they’ll turn the world into a slaughterhouse,” he predicted.

After touring the battlefront, Bethune realized that many of the wounded were quickly bleeding to death or succumbing to shock before ever reaching hospital. Thousands of lives might be saved if he could provide blood transfusions from blood banks maintained directly behind the lines.

It was in this role that Bethune’s team headed along the coastal road in a small ambulance toward Málaga on Feb. 10, 1937, and met the column of refugees. He saw “a silent, haggard, tortured flood of men and women and animals, the animals bellowing in complaint like humans, the humans as uncomplaining as animals.” Dumping the blood bank and equipment at the roadside, Bethune’s team used the ambulance to shuttle hundreds to Almería over a two-day period. He witnessed the killings of countless refugees by strafing aircraft and shelling.

“If we don’t stop them in Spain…,

they’ll turn the world into

a slaughterhouse.”

“What was the crime that these unarmed civilians had committed to be murdered in this bloody manner?” he wrote. Nobody on Bethune’s team knew how many refugees they had spirited to safety.

Prompted by the innumerable orphans he had saved on the road, Bethune lobbied the democratically elected Republican government of Spain and the Canadian committee to establish refugee centres for children. His stubborn sense of purpose soon led to conflicts with the bureaucracy and even suspicion that he might be a fifth columnist. Ordered back to Canada, as much for his own safety as anything else, Bethune left Spain on May 18, 1937. After desultorily participating in a cross-Canada tour aimed at raising support for the Republic, Bethune decided to go to China and join the fight there against Japan. He set off in January 1938. While serving with the Chinese Communist Party’s Eighth Route Army, he accidentally developed septicemia from a surgical cut and died on Nov. 12, 1939. After Mao Zedong memorialized him in an essay for his selfless service, Bethune became a revered hero to the Chinese people.

When one subordinate declared that the Spanish Nationalists must “spread terror…to create the impression of mastery, eliminating without scruples or hesitation all those who do not think like us,” he succinctly summarized General Francisco Franco’s strategy for defeating the Republican government.

After a military coup failed in July 1936, nationalist rebels led by Franco plunged the country into a bitter civil war. Realizing that he was unlikely to defeat the government through purely military action—even with Germany and Italy providing massive assistance—Franco instituted a parallel campaign of terror that reached its zenith when his forces overran the Republican Costa del Sol stronghold of Málaga.

Past atrocities where Republican villages and towns, such as Badajoz, had fallen into Nationalist hands caused such panic that the mass evacuation of Málaga was ordered. Of

the few civilians who remained, at least 4,500 were shot and buried in mass graves. The stream of humanity fleeing along the narrow coastal road toward Almería—200 kilometres distant—was subjected to systematic slaughter. Franco’s troops pursued them with tanks. Fighter planes, flown mostly by German and Italian pilots, swooped down to unleash strafing fire, while naval ships offshore lashed out with devastating gun salvoes. Much of the column was overtaken. All males were shot on the spot, as were many women and children. Others were released because that would leave the Republicans having to feed “useless mouths.” The ragged end of this column took two weeks to reach the dubious safety of Almería. Only 40,000 refugees remained alive.

“The war is over,

but the enemy is

not dead.”

Those who perished constituted a significant portion of the total number of non-combatants killed by the Nationalists over the civil war’s course—with estimates ranging from 100,000 to 500,000 (most recent accounting suggests about 200,000 is probable).

On April 1, 1939, the civil war ended with Franco winning a complete and unconditional victory. But he continued his murderous terror campaign. “The war is over,” Franco declared, “but the enemy is not dead.”

Hundreds of thousands of Republicans were imprisoned. From 1939 to 1943, at least 200,000 of them were summarily executed. Martial law continued to 1948. Franco ruled with an iron fist until his death at age 82 on Nov. 20, 1975. Succeeding him, King Juan Carlos immediately began the transition from dictatorship to democracy, with Spain’s first democratic election in four decades held in June 1977. The following year, the country’s new constitution established a parliamentary monarchy.

Advertisement