Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry fought Canada’s first battles of the Great War in January 1915 at Dickebusch near Ypres, Belgium. [IWM/Q 53135]

You won’t find much about Dickebusch in the annals of Canada’s First World War history. Granted, the name doesn’t have the same cachet to it as a Passchendaele, Somme or Vimy Ridge, but you would never tell that to the boys who were there.

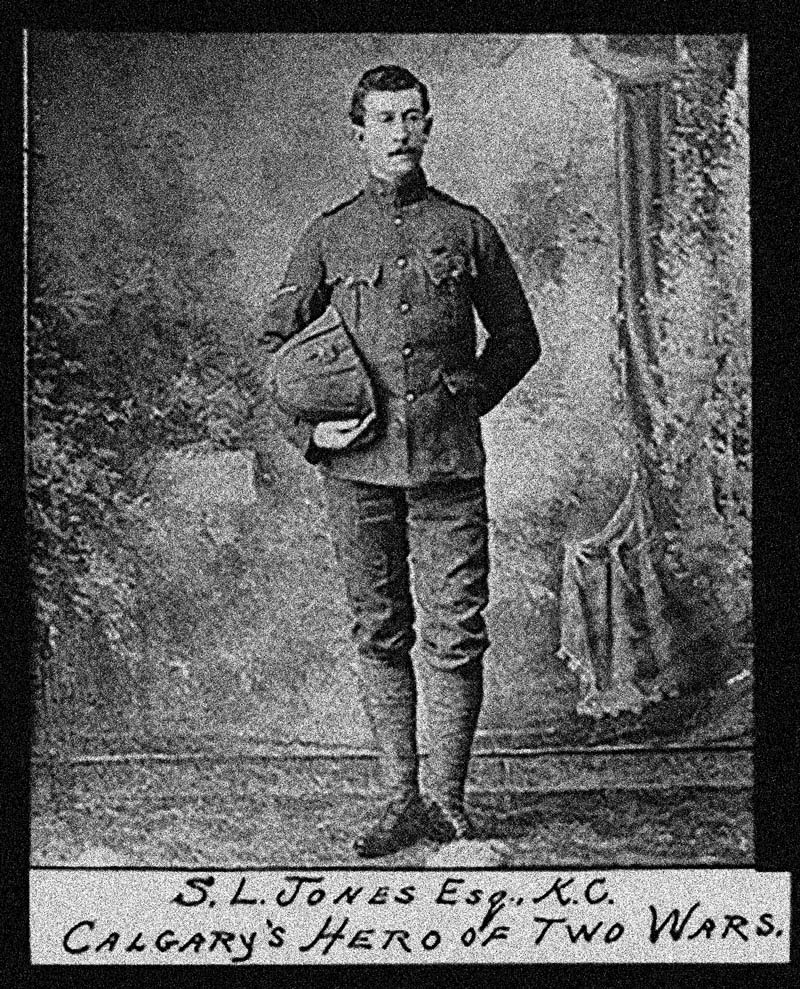

“The German guns suddenly opened on us, and for the rest of the day 17 different kinds of hell were all about us,” wrote Captain Stanley Livingstone Jones, 33, of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI), the first Canuck unit to see WW I action.

After two months of training in England, the Patricias had

followed the No. 2 Canadian Stationary Hospital unit into France, arriving at Le Havre on Dec. 21, 1914.

They were apparently ill-equipped when they moved into the line on Belgium’s Ypres salient on Jan. 6—thanks, no doubt, to Sam Hughes, the controversial federal minister of militia and defence whose cozy deals with suppliers and manufacturers tended to come at the fighting man’s expense.

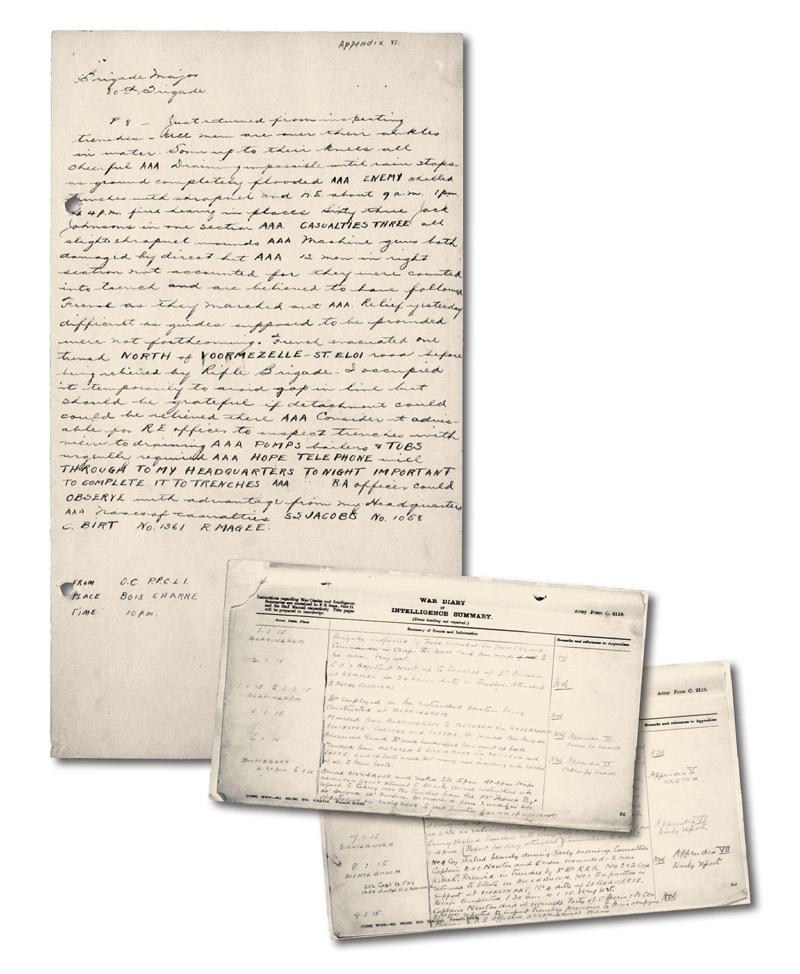

The unit’s war diaries reference inferior equipment and replacing the infamous Ross rifle with the first Lee Enfields taken into front-line Canadian service.[CWM/20070067-003]

The PPCLI had shed the troublesome Ross rifle and its nasty jamming habits in favour of the Lee-Enfield while still in England.

Clothing and footwear were another problem: Boots rotted and uniforms disintegrated in the notorious mud of the Western Front; trenching shovels were useless.

“Lack of boots much felt; many men marching with no soles at all,” says the Patricias’ war diary. “Arrived at Dickiebush [sic] and rested until 5 p.m…. The right half battalion under Major [Hamilton] Gault took over the two sections on the right…. Completed at midnight without incident.

“Trenches were found to be in a very waterlogged condition, no braisers and few dugouts. Distance from German line 40 yards on our left, 200 yards on our right.”

They were just south of the ancient trade centre of Ypres, about 15 kilometres from the French border. Here, the Allies were mounting a stand to prevent German forces from reaching Belgian and French seaports, some 35 kilometres away. The relentless shelling would reduce Ypres and its historic Cloth Hall to rubble.

The standoff would last almost the entire war, the German lines arrayed in a semicircle around Ypres, shifting with the ebb and flow of five major battles and multiple skirmishes in between.

The January 1915 action at Dickebusch appears to be one of those flare-ups, coming two months after the First Battle of Ypres, during which the German advance was stopped in October-November 1914.

There was some apprehension among the British about how the Canadians would adapt to the type and magnitude of the newly industrialized warfare, so different from their last go-round 14 years earlier in the Boer War. Any concerns, however, were soon allayed.

“This front has become a battle of inches and the slightest advance made out of the general scheme endangers our whole front,” a British officer told the Regina Leader-Post at the time.

Trenches were found to be in a very waterlogged condition, no braisers and few dugouts. Distance from German line 40 yards on our left, 200 yards on our right.

Ypres and its Cloth Hall were reduced to rubble during five major battles and relentless shelling between 1914 and 1918.[Henry Edward Knobel/LAC/3403738]

“We were afraid the Canadians, in their enthusiasm, would carry out the rush tactics they employed so effectively in South Africa, but which would be fatal here.

“But the Patricias, rank and file, have shown themselves steady and their officers well trained.”

Indeed, for a forgotten battle, Dickebusch in January 1915 sounded pretty hot.

“Guns of every size and kind roared and spit back and forth, tipping up great holes in the earth and throwing mud and water high in the air,” Jones, himself a Boer War veteran, reported in a Jan. 11 letter to his hometown Calgary Albertan newspaper.

“We escaped annihilation by only a few feet as the main bursts of shrapnel just cleared us.”

Two days after entering the trenches, the PPCLI took Canada’s first casualties of the war on Jan. 8. “No 4 Coy shelled heavily during early morning,” says the history. “Casualties Captain D.O.C. Newton and 5 men wounded: 2 men killed.”

By the time the war ended in November 1918, some 60,000 more Canadians would die, including Jones. And 172,000 would be wounded.

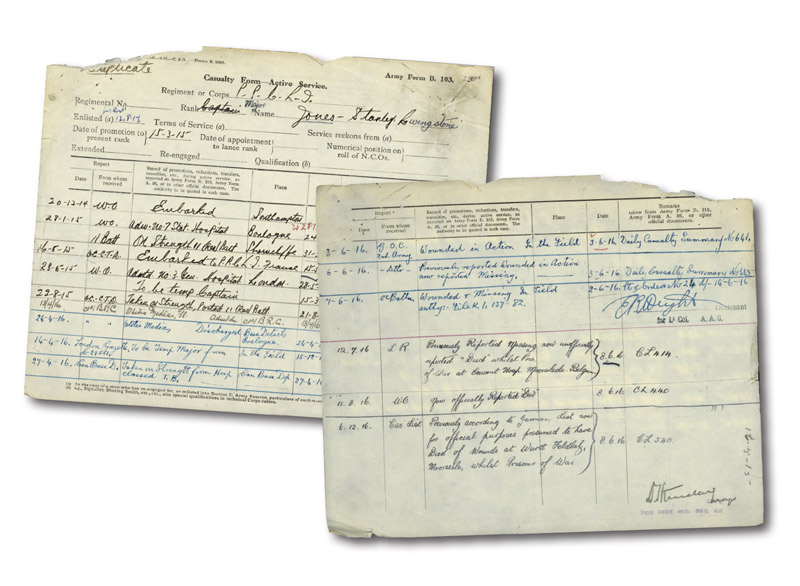

A ruined village in the Ypres salient. Stanley Jones’ service records trace his war journey from recruitment to capture and death.[LAC/3403738]

The Patricias were relieved by the British 3rd Battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps (see “The King’s men,” page 26), and dispatched to billets in the village of Dickebusch, or the Flemish Dikkebus. It’s part of the present-day city of Ypres (Ieper), population 35,000.

Jones would take a bullet to his left hand later in January. He was wounded again by shrapnel to his right foot in May and a

gunshot wound to the left foot in September.

By now a major, he was reported wounded once more, hit by shrapnel through his left lung during a German mortar and artillery barrage near Sanctuary Wood on June 2, 1916.

He “suffered for 36 hours from his wounds with no attention but the first aid given by a comrade,” Alberta’s Crag & Canyon newspaper reported on Aug. 5, 1916.

“The Germans then captured the ground where he lay and, at the risk of their lives, removed him to hospital. They gave him every possible attention.”

Jones died in German hands on June 8. He is buried in Moorseele Military Cemetery, 20 kilometres east of Ypres. His wife Lucile had followed him overseas and was nursing at a hospital in Champigny-sur-Marne, France.

It wasn’t until July 11 that she learned of her husband’s fate. The words “burnt into my head like red hot coals,” she wrote in her memoir. It was days before she could read the rest of the letters that accompanied the news. One was from Jones, mailed on June 4, two days after he was wounded.

“We may be separated for some time but our love will always hold us together,” he wrote.

The PPCLI would fight in what is most commonly regarded as Canada’s first major action, at the Second Battle of Ypres, in the spring of 1915. It was during this fighting between April 22 and May 25 that the Germans first deployed poison gas, hitting French colonials at Saint Julien on the battle’s first day and neighbouring Canadian troops two days later.

Artist Jack Richard depicts Canadians in action at the Second Battle of Ypres in April/May 1915 [Jack Richard/CWM/19710261-0161]

The Patricias had been on the line 12 days and taken 75 casualties, including 26 killed, when they fought a major engagement in the Second Battle of Ypres at Frezenberg in May 1915. Of 700 men who faced fire from three sides and stopped the German advance fighting from ditches and shell holes, 154 emerged in one piece under the command of the only able officer, a 39-year-old lieutenant named Hugh Wilderspin Niven, a wholesale hardware salesman from London, Ont., who had only just recovered from a bullet wound he had taken to his left forearm in March.

Niven was promoted to captain and awarded the Military Cross and the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) the following September. He would survive a shrapnel wound to the chest in June 1916 and return to finish the war a major, receiving a bar to his DSO in January 1918. He died in 1969 at age 92.

Patricia Sergeant Walter Stamper was at Frezenberg, the PPCLI’s most celebrated battle honour and the origin of one of its unofficial mottos, “holding up the whole damn line.” Stamper wrote his wife and daughter in August 1916 after he was captured and eventually deposited in neutral Switzerland, where he would be interned for the duration.

This time, the Canadian prisoners of war didn’t get the same consideration afforded Jones.

“We were simply blown to pieces,” Stamper said. “There was just ten of us left in our Company, most of us unable to help ourselves; those that were to [sic] badly wounded to walk they shot and bayoneted them. These, they made us lay on the ground beside them whilst they dug themselves in.

“All the time the shells and bullets were flying around us, and I can tell you I never expected to see any of you again. To amuse themselves they threw stones at us and called us swine, one of my men could not keep still as he was suffering so from a wound in the head, got up and was promptly shot by them through the stomach; he died about two hours later in great agony.

Guns of every size and kind roared and spit back and forth, tipping up great holes in the earth and throwing mud and water high in the air.

“We laid there from ten o’clock in the morning until six at night when we were fetched into the trench and robbed of everything we had. We were then taken back and threatened if we did not give information about our troops we should be shot. We were lined up three times for that purpose.”

They were eventually put on a train to Germany and given a starvation diet until relief parcels arrived and they were shipped off to Switzerland. There they were boarded in hotels and “smothered in flowers, chocolates, tobacco and cigarettes.”

In his paper “Birth of a Regiment: Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry 1914-1919,” historian James S. Kempling writes that the fighting that spring “marks not the death of the Originals but rather the initial birth pangs of a Regiment.”

“Nevertheless,” he continued, “by the end of the Frezenberg battles the Patricias were in desperate condition. In May alone the battalion had 461 men struck off strength. Of these 219 had been killed and most of the remainder injured to the extent that they were unlikely to return to duty. A small number had been taken prisoner.”

The regiment would reconstitute and go on to fight at Mount Sorrel, the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele (the Third Battle of Ypres) on into the Hundred Days Campaign that finished the war.

Of the 5,000 men who served with the regiment during the First World War, 1,300 never returned to Canada. Three Patricias would earn the Victoria Cross and the regiment would receive 18 battle honours.

During April 1916 fighting for the St. Eloi Craters five kilometres south of Ypres, elements of the Saskatchewan Rifles were billeted in reserve at the Patricias’ old haunt in Dickebusch. James Cameron McFadden’s grandfather, James Muirhead, was with the battalion.

In a Facebook post with a photo of his grandpa, great-granddad and great-uncle, who was killed at Ypres in 1916, McFadden said Muirhead rarely spoke of the war, but he was fond of one story about that favourite of infantry mascots—a dog.

We were simply blown to pieces. There was just ten of us left in our Company, most of us unable to help ourselves.

A soldier stands at a monument alongside Patricia Crater, where engineers and PPCLI took a German position during early fighting at Vimy Ridge.[LAC/3379697]

“Somewhere in a place that the men called ‘Dickie-Bush,’ [they] befriended a small dog, and it followed them wherever they were sent throughout the rest of the war,” wrote McFadden. “They just called it ‘the Dickie-Bush Terrier,’ after the place where it had joined them.

“When the war was over, they were told that they could not bring the dog home with them. One of the men scooped him up and hid him inside a duffel bag, and they all went onto the transport ship home to Canada. Grampa said that the last time he saw the dog, it was at the train station in Toronto. It was running after the man who had put it in the duffel bag.

“It followed him right up the steps onto a Pullman car, destined for a new home.”

Advertisement