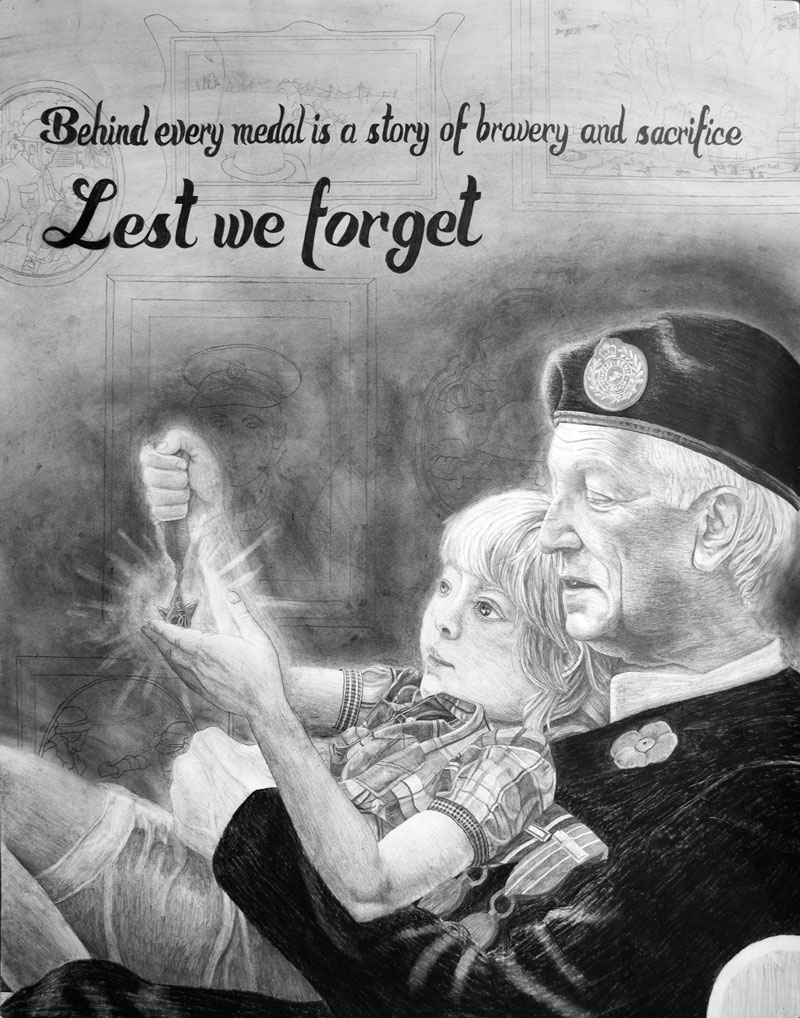

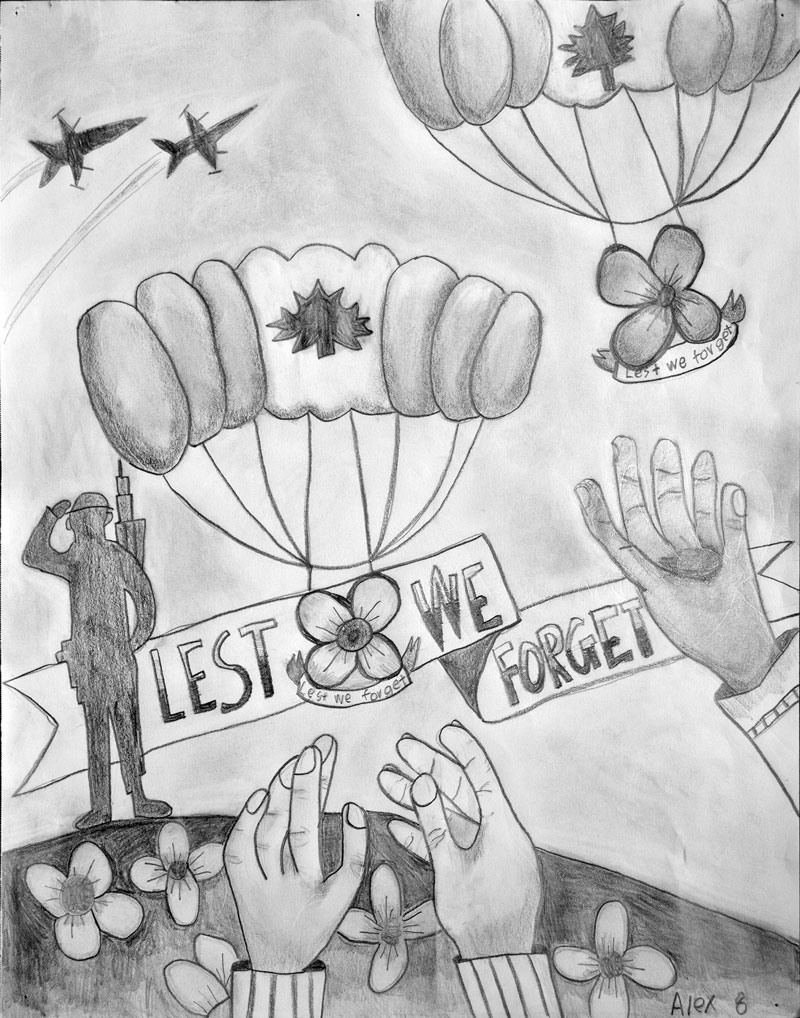

The first-place senior black and white poster by Yuet Leung of Markham, Ont.

It is a great paradox of war that a source of immeasurable heartbreak, suffering and loss has, over the centuries, inspired some of history’s greatest art and literature.

Disproportionate volumes of conflict-related works have been devoted to glorifying the sanctioned killing of people. The best, however, expose the rawness and futility of humankind’s greatest failings in ways that touch even those who might rather not confront war’s uniquely commanding ugliness and beauty.

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, depicting the April 1937 bombing of a bastion of Republican resistance during the Spanish Civil War, is widely regarded by art critics as the most moving and powerful anti-war painting ever made.

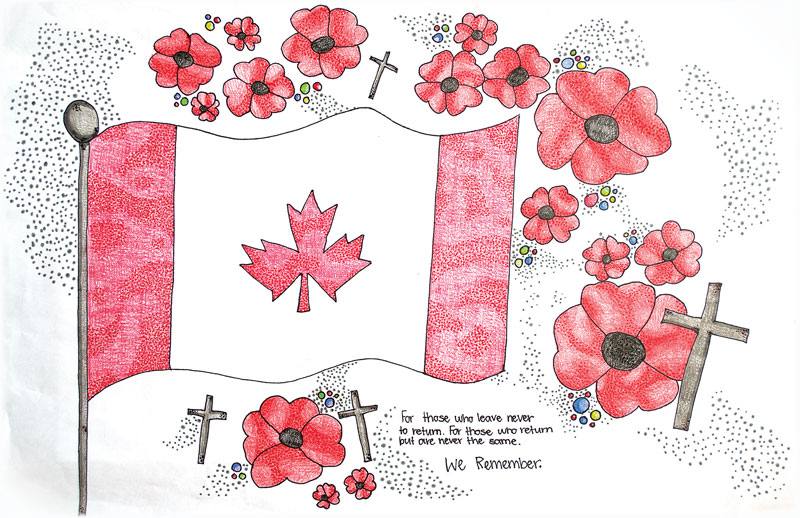

Likewise, the John McCrae poem In Flanders Fields, written on the Ypres battlefield in Belgium in 1915, is in its essence an exquisite anti-war protest, its opening words known the world over: “In Flanders Fields, the poppies blow/Between the crosses, row on row…”

Each year, Royal Canadian Legion branches across the country sponsor poster and literary contests for students from primary school through high school, the winners of which advance to provincials, where the best are sent on to the national competition, judged and exhibited in Ottawa.

Inevitably, there are surprises, not just in the technical talents of the artists and writers, but in the depth of perspectives that emerge from big cities, small towns and isolated villages in the farthest corners of this vast country—insights that transcend the youth and experience of their creators and move and challenge the public.

its colour counterpart by Eugena Lee of Calgary both focus on intergenerational connections of remembrance.

Rachel Graham, a 16-year-old high school student from Salmon Cove, a village of nearly 800 on the west shore of Newfoundland’s Conception Bay, put herself in the shoes of a soldier in mourning with My Friend, which won the senior poem category in 2022.

“In the fields where we once fought gallantly, the flowers now reside/but here I am forced to stand alone, without you by my side,” she began. “Where once the sounds of warfare, unbearable to the ear/is now a deafening silence, of you not being here.”

Her thoughtfully crafted words took the sweeping scale of war to its simplest, most relatable level: the loss of a friend—youthful innocence and naïveté confronted too soon by a profound pain that all of us will eventually know in one way or another. Graham continued: “We did not know the hardships, that were waiting for us there/the war is so unforgiving, taking lives without a care.”

There are winners as diverse in origin as senior essayists Aarika Haque from Elrose, Sask. and runner-up Lauren Hollett from Dildo, N.L., to the top junior and primary black-and-white artists Ella Ng of Calgary and Alexander Gan of Kanata, Ont., a suburb of Ottawa.

The majority of winners come from small- to mid-sized villages and towns with names such as La Glace, Alta., a village of about 200 residents where Kate Goodward produced the intermediate-winning essay, The Poppy, and Cut Knife, Sask. (population nearly 600), home to intermediate black-and-white runner-up Akeira Anseth.

There are names from Charlottetown; Cavan, Ont.; Humboldt, Sask.; Mont-Carmel, Que., and Port Hawkesbury, N.S.—places where the Legion remains a central gathering place and a valued community resource devoted to good works.

The Legion National Foundation brings the senior winners to the national Remembrance Day ceremony in Ottawa, where they meet the Governor General and place a wreath on behalf of Canada’s youth.

Winners in the four categories—essay, poem, black-and-white poster and colour poster—from each of four divisions are exhibited at the Canadian War Museum in the nation’s capital for a year. Second-place finishers and honourable mentions are displayed on Parliament Hill in November.

Intermediate posters first place

The winning intermediate colour poster by Elysa Goyette of Chicoutimi, Que., pays tribute to a diversity of modern-day force members.

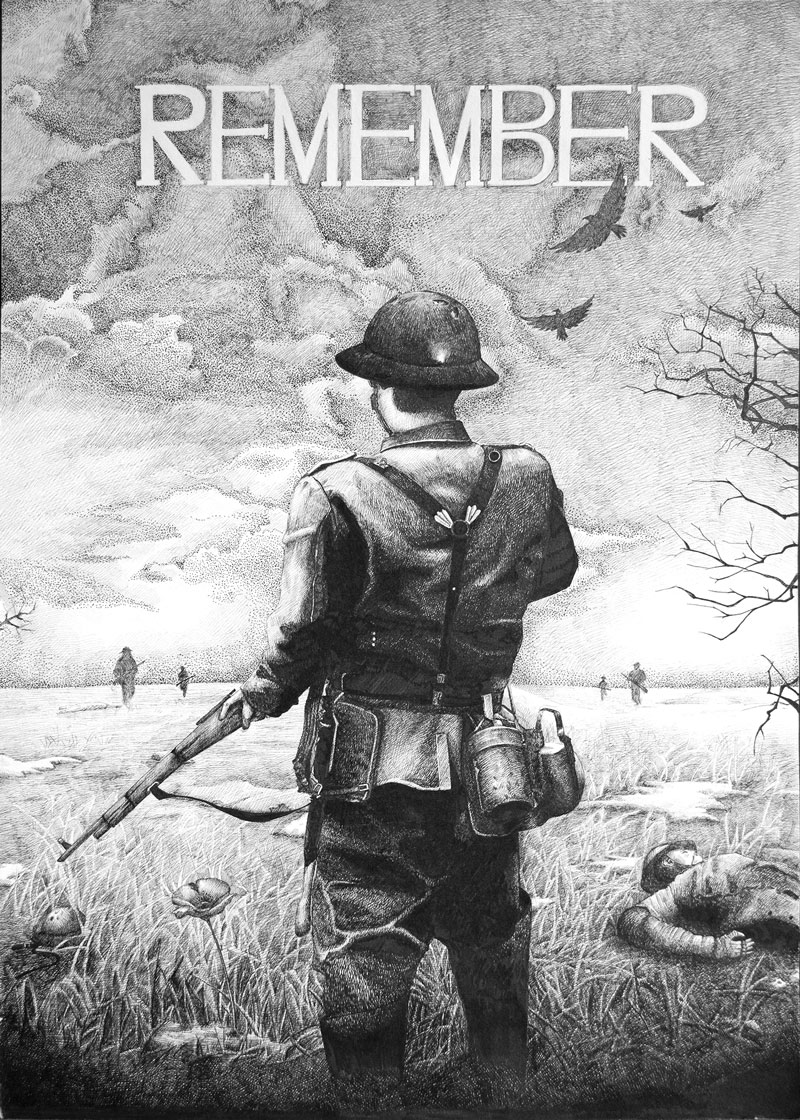

The winning intermediate black and white poster by Si Yan (Sam) Li of Langley, B.C., portrays a soldier afield reflecting on fallen comrades

Junior posters first place

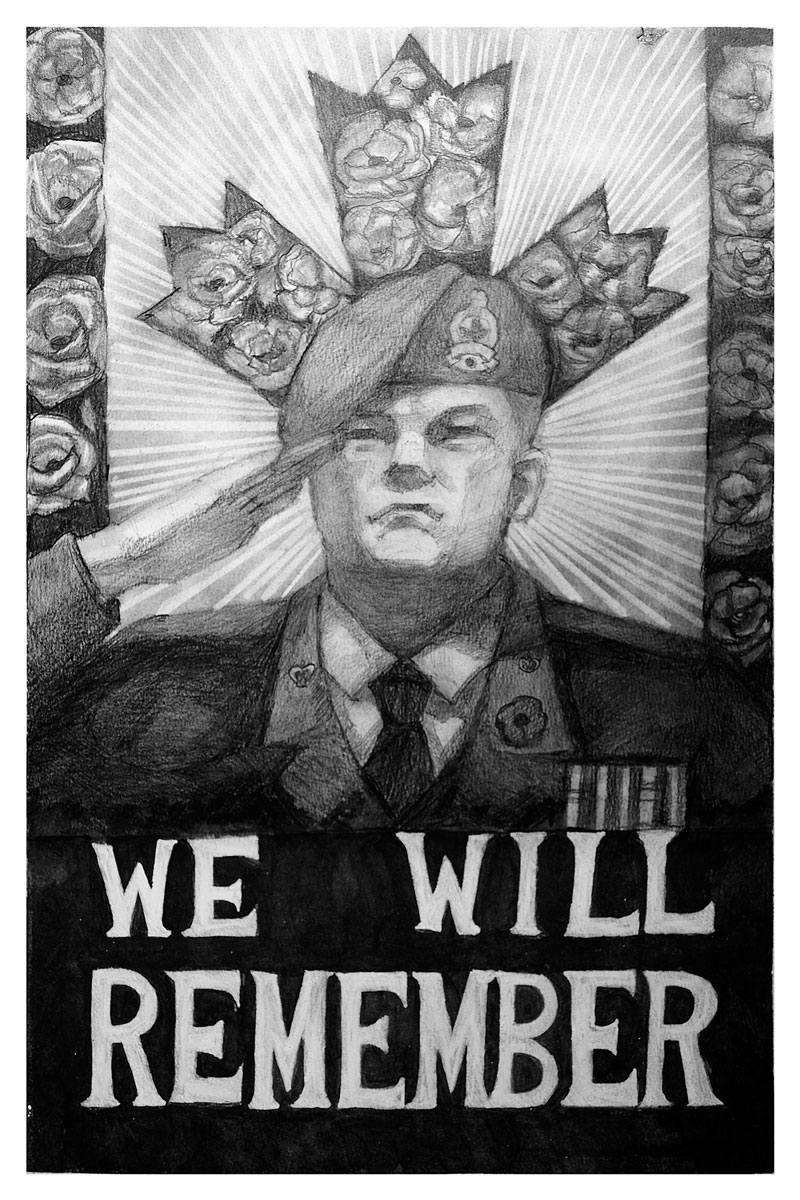

Ella Ng of Calgary produced the first-place junior black and white poster featuring a saluting veteran in front of a poppy-laden flag.

Primary posters first place

the simple yet powerful image of a silhouetted soldier amid a field of poppies won Khadijah Varteji of Maple, Ont., first place in the primary colour poster category.

Alexander Gan of Kanata, Ont., won the primary black and while poster contest with his depiction of poppies dropping from the sky.

Advertisement